In places most prone to wildfires and hurricanes, state “insurers of last resort” are absorbing trillions of dollars in risk.

By Leslie Kaufman,

Saijel Kishan and Nadia Lopez

Illustrations by John Provencher for Bloomberg Green

March 5, 2024 at 7:00 PM EST

It is so easy to start a wildfire. A smoldering campfire, a lightning strike, an errant firework or a spark from a power line or a hot muffler: However California’s next monumental blaze begins, the toll will be vast. People will be injured, some will die. Thousands of homes will be destroyed.

When the smoke clears, the most populous US state, home to Hollywood, Silicon Valley and a real estate market worth more than $9 trillion, will be ground zero for a sweeping financial crisis.

Some 11 million people live in California’s high-risk wildfire zones, areas that include Los Angeles county, San Diego and the vineyards of Napa and Sonoma. Not long ago, they and homeowners in natural disaster regions around the US would have almost certainly had insurance through a big, national company like State Farm General Insurance Co., Allstate Corp. or Hartford Financial Services Group Inc.

Uncovered: Part 1

This story is part of Bloomberg Green’s investigation into how climate change is making parts of the planet uninsurable, leaving millions of people without a safety net. Governments and companies aren’t prepared.

But a growing number of insurers are cutting their business in those areas, deterred by more intense and frequent natural disasters, plus state-imposed limits on how much they can charge. Homeowners in the most risky places are now more likely to be covered by state-created, “last resort” insurance programs that provide protection where the private market won’t.

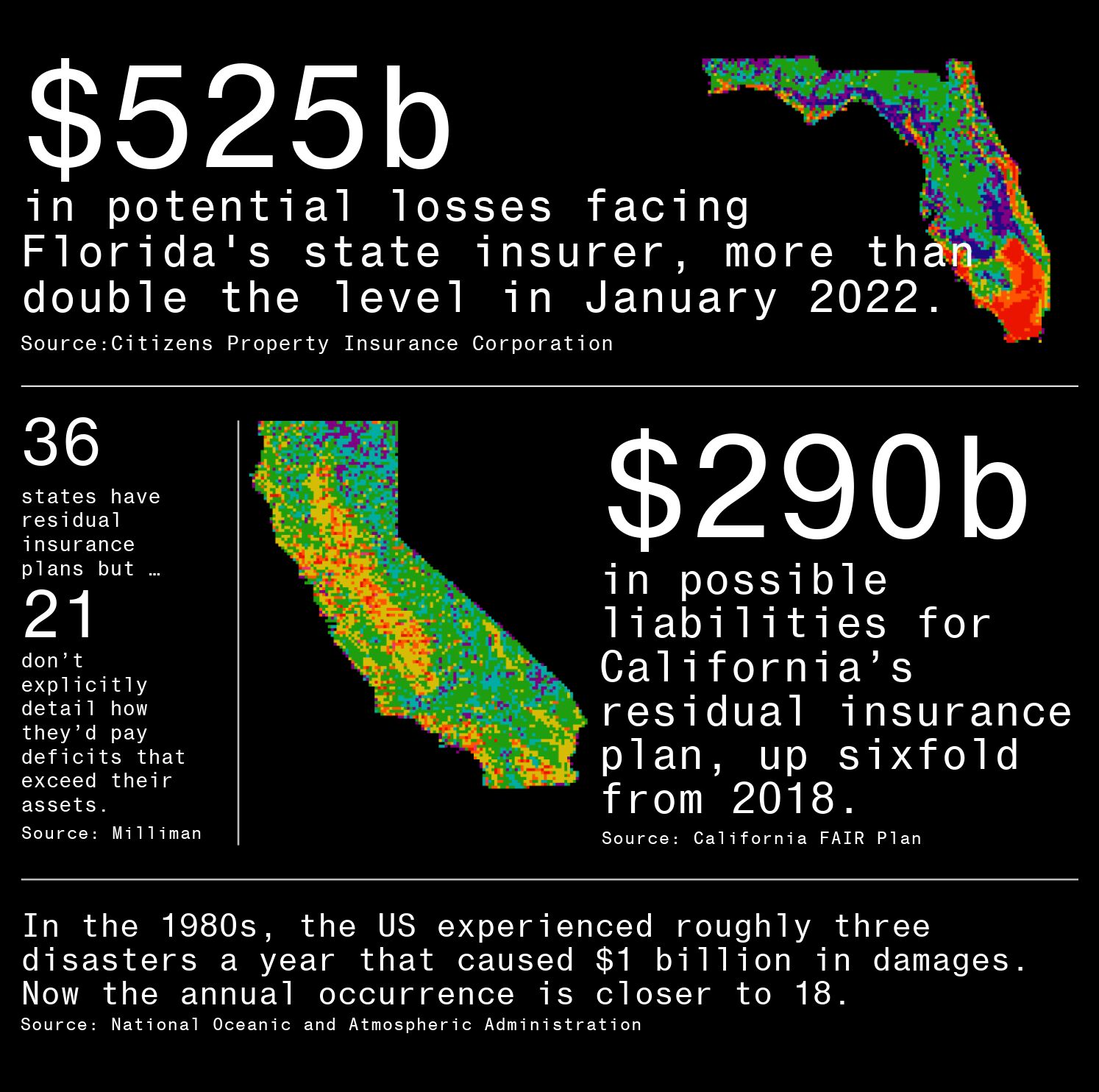

Those plans have more than doubled their market share since 2018, and their liabilities crossed the $1 trillion threshold for the first time in 2022, according to Property Insurance Plans Service Office Inc., a research firm that tracks the programs. The most climate-vulnerable states are the most exposed: As of now, Florida’s plan could suffer $525 billion in losses; In California, it’s at least $290 billion, up sixfold from 2018.

But even as states have assumed more and more risk, they’ve largely dodged a fundamental question: How will they cover claims in the wake of a truly major catastrophe? There are limited options—levies on private insurers or state residents, or more state borrowing—and none of them are good.

An aerial view of a Paradise neighborhood destroyed by the Camp Fire in 2018, and then the same view a year later when the homes and debris have been cleared. Photographer: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Most states haven’t thought this far ahead, or if they have, they’re not explicit about where the money will come from. Out of 36 residual insurance plans that offer coverage for natural catastrophes, 21 don’t explicitly detail how they’d pay deficits, according to new research from consulting group Milliman.

States have turned these plans into “a magic hiding place to disappear risk that just gets too big for the private market,” said Nancy Watkins, a principal and consulting actuary based in Milliman’s San Francisco office.

Federal lawmakers have begun to take notice of the conjoined problems of rising risks and higher costs. US Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, a Democrat from Rhode Island, is investigating the possibility that a big-enough disaster on Florida’s coast might trigger a national real estate crisis, or push the state’s residual insurer to seek a federal bailout. Meanwhile, Representative Adam Schiff, a Democrat from California, has proposed a national catastrophic reinsurance program, similar to the longstanding—and chronically indebted—National Flood Insurance Program.

California is one of those states that doesn’t explicitly spell out what it will do if claims force it into deficit. The state department of insurance says that current rates are adequate to cover losses, and that there are safeguards in place to make policyholders whole. But the Personal Insurance Federation of California, an industry trade group, disagrees. It points out that the state can’t know whether rates would cover losses because the plan hasn’t performed the kinds of stress tests designed to understand the consequences of another bad fire season.

California’s plan has no more than a general idea of what it could owe, how much it could fall short, or what kind of burden might fall to the private insurers—companies that have already declined to cover the riskiest parts of the state.

In a statement, the California Department of Insurance said it performs a triennial examination of the residual insurer to “evaluate the financial condition, assess corporate governance, identify current and prospective risks, and evaluate system controls and procedures used to mitigate those risks.”

The plan isn’t subject to the kinds of capital requirements designed to prevent private insurers from taking on too much risk, according to the statement. A spokesperson for the plan said that “information regarding [its] financial situation isn’t publicly disclosed.”

It’s hard to overstate the role that insurance plays in the modern American economy. Banks won’t make mortgage loans for uninsurable properties; without those loans, the real estate market slows to a crawl, which in turn eats away household wealth and the tax revenue that state and local governments rely on.

For insurers to play their part, they have to feel confident predicting how much damage they might have to cover. To do that, they build models of the future based on what’s happened in the past. They don’t have to be right all the time, just enough to win more than they lose.

Climate change has made that much harder. A warming world is more dangerous and unpredictable. In the 1980s, the US experienced roughly three disasters a year that did at least $1 billion in damage. Now the annual occurrence is closer to 18, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and likely to rise.

Boats piled up in Fort Myers, Fla., in the aftermath of 2022’s Hurricane Ian, the first storm to cause $100 billion in damages in the state. Photographer: Ricardo Arduengo/AFP/Getty Images

Private insurance companies are required by law to balance those risks with assets, typically a mix of plain vanilla investments, and hedges that include more complicated products like catastrophe bonds or reinsurance. They feed that stockpile with revenue from premiums. As the risks rise, so do the prices, sometimes to levels beyond what state regulators or policyholders will accept. When market conditions become too hostile, private insurers limit their exposure in a different way: They stop writing new policies.

When property owners see premiums skyrocketing or private insurers leaving, it’s one signal that the risks of disaster have grown beyond what the market will bear. Maybe it’s no longer safe to live—or at least, to invest significant wealth—in such places. Maybe it’s time to move.

That’s not a popular message for homeowners or their elected representatives, a group that includes, in 11 states, the insurance commissioner. Given the central role that insurance plays in the real estate market and, therefore, state revenue and population growth, politicians are tremendously motivated to keep insurance prices low, muting that market signal.

Florida, for example, was hit by eight hurricanes in 2004 and 2005. In his campaign for governor the next year, then-Republican Charlie Crist promised to freeze premiums charged by Citizens Property Insurance Corp., the state’s insurer of last resort. When he took office in 2007, he scuttled a 75% planned increase.

He set an important precedent. Florida, which has some of the riskiest assets in the US, has kept Citizens’ premiums at far less than the private market for storm insurance. Its policy count has almost tripled since 2018.

If Citizens faces a shortfall, it will allow insurance companies to levy a fee on every policy in the state. That means anyone with property insurance would be on the hook.

Historically, those assessments have been small, but that’s no guarantee. According to a 2018 study by the University of Cambridge and Munich Re, if a Category 5 hurricane hit Miami and the Florida coast, it could cause a staggering $1.35 trillion in damages, more than $60,000 for every person in the state.

Even a much smaller amount could stretch the means of the state’s significant retiree population, said Whitehouse, who leads the Senate Budget Committee. In November, he launched a probe into Citizens, asking for information about how it manages climate-related losses.

“The problem is that the numbers spin out of control once you look at them,” he said in an interview. “We’re afraid that’s a sign, that they know perfectly well that their numbers don’t add up and that they’re in deep, deep trouble. They just don’t want to admit it.”

Michael Peltier, a spokesperson for Citizens, referred Bloomberg Green to a letter the organization sent to Whitehouse in December, which says that it buys reinsurance and has ample reserves and financing options. It also noted that it can levy assessments on policyholders across the state and said its structure ensures it will always be able to pay its claims.

Whitehouse, though, is concerned that Citizens might need to appeal to the federal government for help, with Lehman Brothers-style arguments both for and against. “If Florida is the leading edge of the predicted coastal property values crash, it could lead to an economic meltdown similar to 2008,” he said.

California’s insurance crisis dates to Proposition 103, a 1988 ballot initiative that rolled back existing rates, then among America’s highest, and subjected future increases to state approval. Its supporters like to point out that Californians have saved $150 billion in premiums over the last 25 years. The insurance industry says those price caps have undermined its ability to do business in the state.

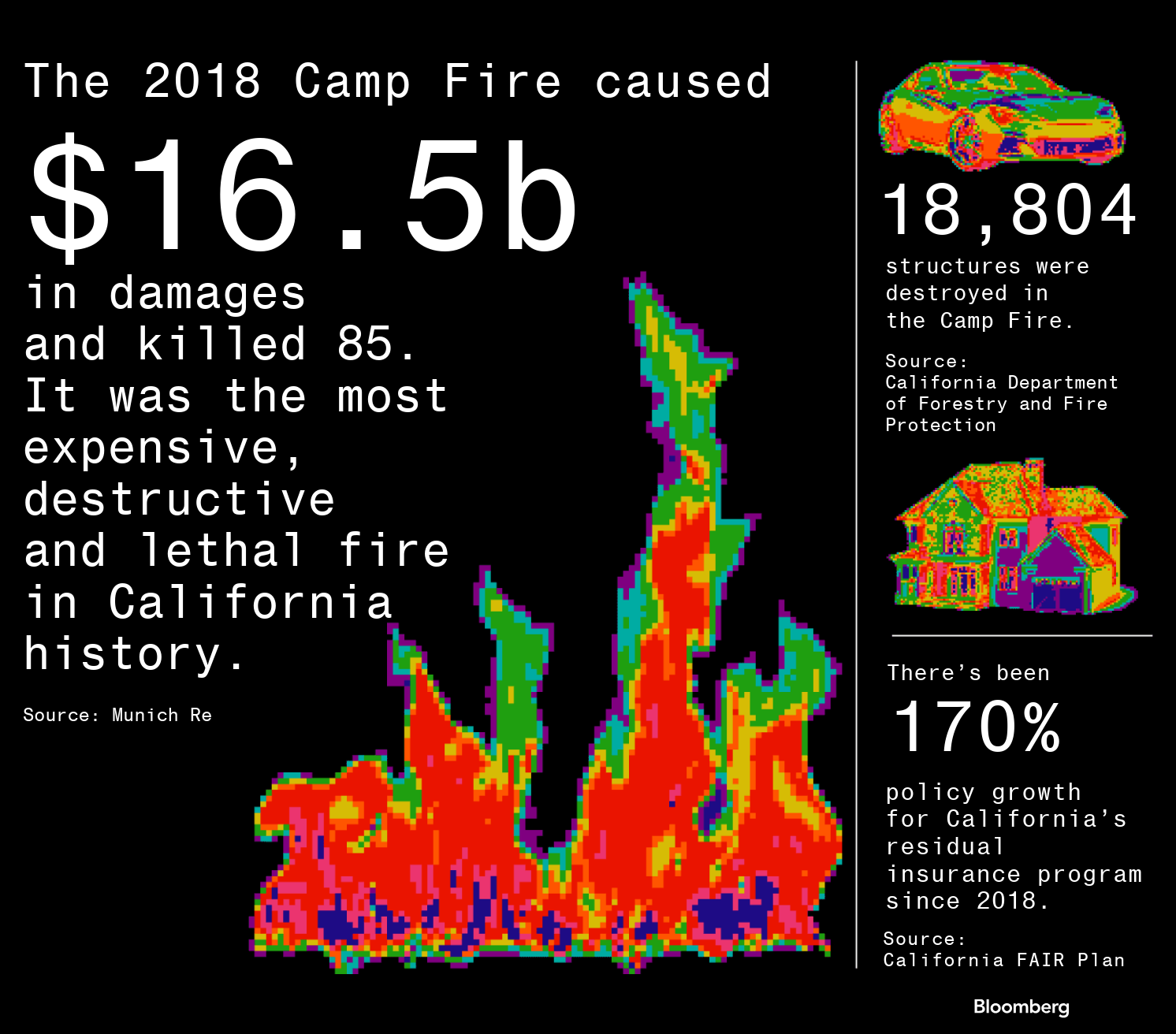

Thirty years later, a spark from a faulty electric transmission line started a fire that quickly spread over tinder parched by years of drought. What became known as the Camp Fire burned for more than two weeks in 2018, demolished almost 19,000 buildings, caused $16.5 billion in damage, killed at least 85 people, and left dozens more missing—making it the most expensive, catastrophic and lethal fire in the state’s history.

The 2021 Dixie Fire spanned five counties and nearly 1 million acres in northern California. Photographer: Josh Edelson/AFP/Getty Images

For private insurers, the losses were stunning. Fire damage from 2017 and 2018 wiped out more than twice the previous 25 years’s worth of underwriting profits for the California insurance market, according to Milliman.

The industry recouped some money from the utility that owned the transmission lines and premium increases as much as the state allowed, but it was still an ominous sign. The five biggest blazes of the 2020 season destroyed another 7,800 structures across almost two million acres.

Combined with state restrictions on how insurers are allowed to account for climate change, a growing number of big insurers have decided that California’s no longer viable. State Farm, USAA, Allstate, and the Hartford have either stopped writing new homeowners policies or limited coverage across the state. In 2021, roughly 13% of total voluntary home and fire insurance policies weren’t renewed.

State Farm and USAA didn’t respond to messages seeking comment. A spokesperson for Allstate said the company is working with California’s insurance commission to help improve coverage availability, and offer more policies using wildfire modeling and reinsurance. A spokesperson for Hartford Financial said the insurer stopped offering new homeowners policies in February. “We need to be able to price our homeowners’ insurance appropriately for the risks we are protecting against,” she said.

California’s newly uninsurable homeowners have turned to the state’s residual insurance plan. Since 2018, the number of policies has grown 170%. Now it typically receives 1,000 new applications a day. Though the plan doesn’t make its finances public, a state report estimates it’s holding roughly $100 million in reserves as of 2021—less than 1% of the insured losses from Camp Fire.

To cover any shortfall, the state plan will assess private insurers proportionally to their market share. As far as the state’s concerned, the insurers are on the hook for the most fire-prone properties, even if they’ve already decided the numbers don’t add up.

If a catastrophic event triggers a massive assessment, it could force some insurers into bankruptcy, said Rex Frazier, head of PIFC. “Or would the state step in and say, ‘no, we’ll allow them to put a surcharge on all of their policyholders.’ Who knows? We don’t have the answer.”

For companies that live and die by their ability to forecast and manage risk, that kind of uncertainty poses a real problem. Ultimately, a critical mass of insurers could exit California. Or they could start to exclude wildfire coverage. In that case, the state could have to step in with its own plan at a cost borne by everyone in the state.

Thad Eggen in the dining room of the Twin Owls Steakhouse in Estes Park, Colo. He and Sandra Huerta own the restaurant and the adjoining Taharaa Mountain Lodge. Their insurance premium went up 75% last year. Photographer: James Stukenberg for Bloomberg Green

“It would be like Obamacare for property insurance,” said Jeff Engelstad, a professor of real estate and construction management at the University of Denver. “That would be a shame, because it’s not the most efficient model. But a market solution would be too severe.”

Ricardo Lara, California’s insurance commissioner, is advocating for what he calls “the largest insurance reform” in the state since Proposition 103. His plan would enable insurers to raise rates more quickly and to allow for increases based on forward-looking climate change data and reinsurance costs, changes he says will stabilize the market.

Homeowners don’t understand disaster risk the same way that actuaries do. Moving is a headache under the best of circumstances; for individuals or families, it can seem like a crazy response to a theoretical future disaster. And while humans expect risks in general, we tend to discount the likelihood that any particular bad event will happen to us.

Thad Eggen co-owns an 18-room lodge and steakhouse near Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park, about 66 miles (106km) northwest of Denver. During 2020’s East Troublesome wildfire, guests could see thick plumes of smoke billowing up over nearby mountains from the lodge dining room.

Smoke rises from the 2020 Cal-Wood Fire as it burns in Boulder County, Colo. Wildfires have made the state increasingly unprofitable for private insurers. Photographer: Matthew Jonas/MediaNews Group/Boulder Daily Camera/Getty Images

Snow and firefighters stopped the flames before they reached Eggen, but it left him with fear. “We’re sitting in a tinderbox,” he said “I constantly worry that this park could go up in flames.”

Insurance companies were prone to agree. Damage from wildfires and hailstorms made Colorado one of the least profitable states for home insurers in the five years through 2021. As a result, premiums in the state jumped more than 50% between 2019 and October 2022. Even so, three-quarters of home insurers reduced their exposure to the state in the first 10 months of 2022.

Last year, Eggen discovered his premium would surge from $40,000 to $400,000. His insurance broker told him it wasn’t a typo. “It was bizarre, I was in denial,” Eggen said. “I thought I may as well hand the keys to my business to the bank.”

What he didn’t consider, though, was moving. Other places have their share of natural disasters, he figured. Eventually, he found another insurance company willing to cover him for a relative bargain of $70,000. “I am just taking it year by year.”

Last spring, Colorado passed a law to create a new insurance plan, the first state to do so in decades. They had no other choice, said state Representative Judy Amabile, a Democrat who co-sponsored the legislation. Without affordable insurance, she said, “there’ll be no real estate transactions, no businesses, hotels, stores. Insurance is pretty fundamental to keep things going.”

As in other states, Colorado will require private insurers to participate in order to do other business in the state. It’s supposed to be financially sound and providing coverage only to those turned down by the private insurers at premiums that reflect risk. Details about how the plan will manage the risk or what it will charge haven’t yet been made public. It’s scheduled to start writing policies in 2025.

One way or another, it may come back to taxpayers, said Colorado Insurance Commissioner Michael Conway. “If climate change is beginning to increase claims and payments, which ultimately it is, it’s fundamentally the consumer and society in general that bears the brunt of that,” he said.

State Senator Brian Dahle sits in the burn scar of the 2021 Caldor Fire in Bryants, Calif. He’s proposed legislation to help areas ravaged by wildfire and has called on the insurance commissioner to make coverage more available and affordable. Photograph: Max Whittaker for Bloomberg Green

When insurers and consumer advocates talk about how to address the growing risks presented by climate change, they often mention the importance of “hardening,” the industry term for how individual homeowners can limit damage.

In a fire zone, that includes using “ignition resistant” building materials and creating a buffer zone with no vegetation; in flood-prone areas, it could include battery-operated sump pumps, or elevating houses with stilts.

There are essentially two tools to encourage homeowners to make these kinds of changes, often at considerable cost. Insurers can offer discounts, and the state and local governments can update the building codes. The latter is immediately effective for new construction. Older homes typically don’t have to conform until their owner wants to renovate or sell.

Even then, there are limits. Improvements in Florida’s building codes mitigated exposure by more than 90% compared with the 1970s, according to recent analysis by Swiss Re. But at the same time, strong hurricanes have become more frequent, and with the state-sponsored insurance program backstopping real estate transactions in the riskiest areas, more people have moved in. This “population-amplifying loss potential,” as the study calls it, rose to more than 180%.

In the effort to shield residents from short-term price hikes, residual insurers effectively subsidize the owners of vast swaths of real estate, said Robert Hartwig, a director at the Risk and Uncertainty Management Center at the University of South Carolina.

“We’ve been incentivizing people to locate properties in hazard-prone areas for many decades,” he said. “It’s a legacy that we’re going to have to deal with.”

California State Senator Brian Dahle, a Republican whose district was ravaged by the Camp Fire, says catastrophes cast a long shadow. Many communities have yet to fully recover from their financial and personal losses. Not everyone has chosen to stay—the population of Butte County has declined 10% since 2018, compared with a 1% drop for the state as a whole during the same period.

Those who remain call Dahle’s office to say they can’t find insurance or are paying premiums higher than their mortgages, even after “fire-proofing” their properties. He’s a strong advocate of home hardening and has backed several bills designed to decrease the risks to his constituents and provide some measures of relief.

Ultimately, though, he says, this is the insurance commissioner’s problem to fix. “I don’t know what the future holds,” he said. “I know one thing: There’s some things we can do and some things we just have to just pray about and wait and see what happens.”