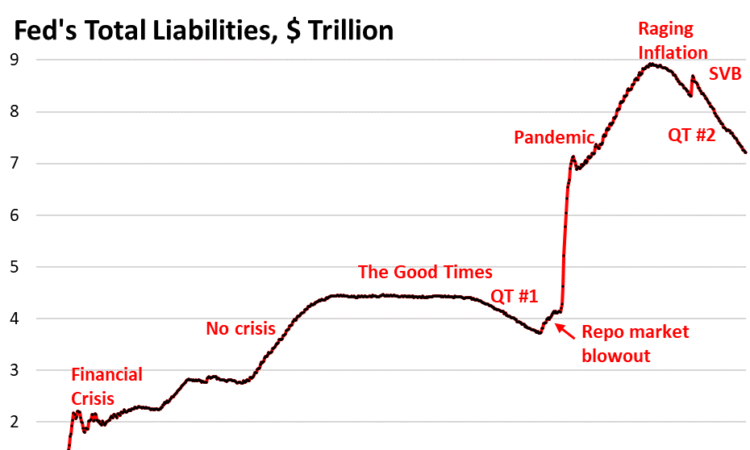

Fed Liabilities under QT Drop $1.71 Trillion, to $7.22 Trillion: Reserves, ON RRPs, Currency, TGA, Foreign Official RRPs

The liquidity drain of Quantitative Tightening has come entirely from ON RRPs. Reserves have lots of liquidity left to drain.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

Total liabilities on the Fed’s balance sheet have dropped by $1.71 trillion since the end of QE in April 2022, to $7.22 trillion, the lowest since December 2020, according to the Fed’s weekly balance sheet today. The liabilities have dropped as a result of QT, in lockstep with the Fed’s assets, which have also dropped by $1.71 trillion over the same period.

There are five big liabilities. Two of them – “reserves” and “ON RRPs” – are hotly discussed by Powell and Fed governors, and by everyone on Wall Street, because they represent liquidity in the financial system that is now getting drained by QT:

- Reserves: cash that banks deposit at the Fed

- Overnight reverse repurchase agreements (ON RRPs): cash from domestic counterparties, mostly approved money market funds

- Currency in circulation: paper dollars in pockets and under mattresses globally

- Treasury General Account (TGA), cash the government puts into its checking account

- Reverse repurchase agreements with foreign official counterparties.

The Fed’s assets are mostly securities and loans. The Fed’s liabilities are forms of liquidity – cash that the Fed owes other entities.

During QE, the Fed’s purchases of securities pumped up its assets to nearly $9 trillion, and its liabilities followed in lockstep because a balance sheet must balance. On any balance sheet: assets = liabilities + capital. The Fed’s capital is fixed by Congress, so what moves in lockstep are its assets and liabilities.

The two liabilities that move with QE/QT.

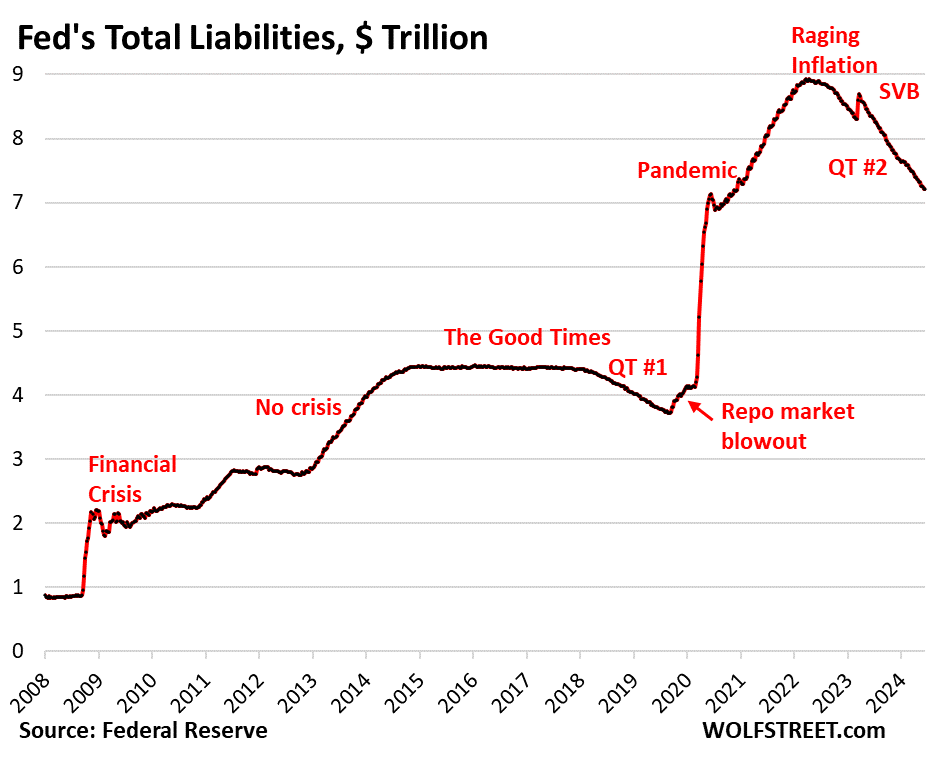

Reserves: -$265 billion since the beginning of QT in July 2022, to $3.46 trillion.

Reserves are liquidity in the banking system. Banks pay each other out of their reserve accounts at the Fed once a day. They’re the center of the US payments system for banks. The Fed has been paying banks 5.4% in interest on their reserve balances since the last rate hike in July 2023.

QT is draining liquidity from the financial system, and reserves are one place where this liquidity drains out of. But it’s not the only place – the Fed’s ON RRPs are mostly where the QT liquidity drain has taken place so far.

Cash also shifted between reserves and ON RRPs. Reserves peaked just before the Fed began tapering QT in late 2021, then fell sharply as the funds shifted to ON RRPs via the money markets. Since that December 2021 peak, reserves have dropped by $821 billion.

The level of reserves is what the Fed looks at to determine how far it can take QT. Toward the end of QT-1, reserve balances dropped so low (below $1.4 trillion) that banks stopped lending to the repo market, even as repo rates began to rise sharply and it would have been profitable for banks to lend to the repo market. And so the $5-trillion repo market blew out, and the Fed ended up stepping in to calm the panic, thereby undoing a big part of QT-1.

As a result of this repo market blowout in 2019, the Fed, in July 2021, revived its Standing Repo Facility that it had killed in 2009 during QE, and that it then didn’t have in September 2019 when it needed it. The SRF is designed to supply cash to approved banks via repos, the way it had done it before 2009. Banks can then use this cash to lend to the repo market at higher rates and make money on the spread.

Powell and other Fed governors have said that no one knows how low reserves can drop without causing issues in the banking system – they’re shooting for “ample” reserves, down from the currently “abundant” reserves. And they will keep their eyes out for signs that they’re approaching that ample level, they said.

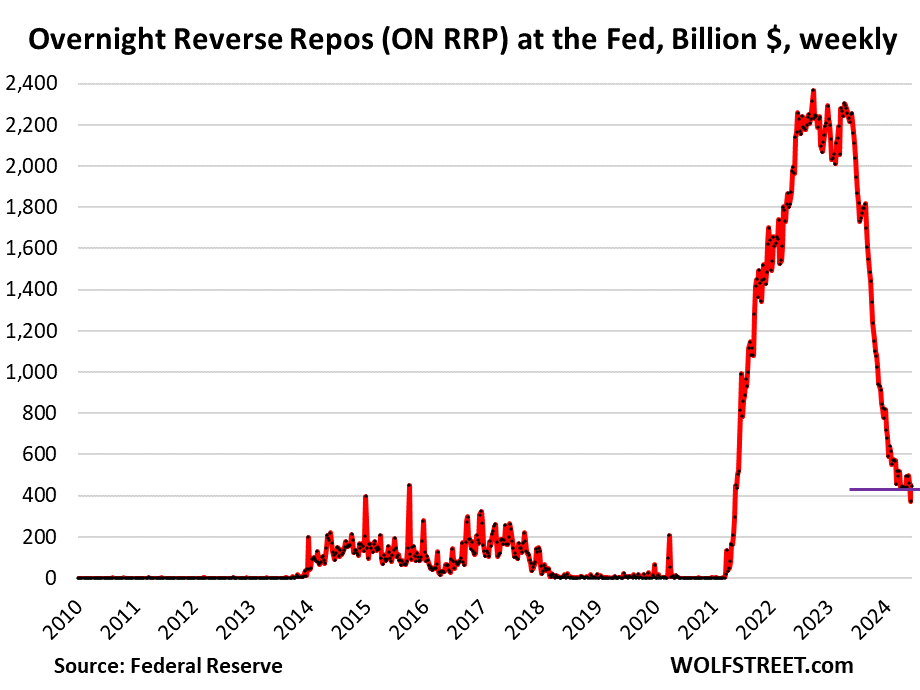

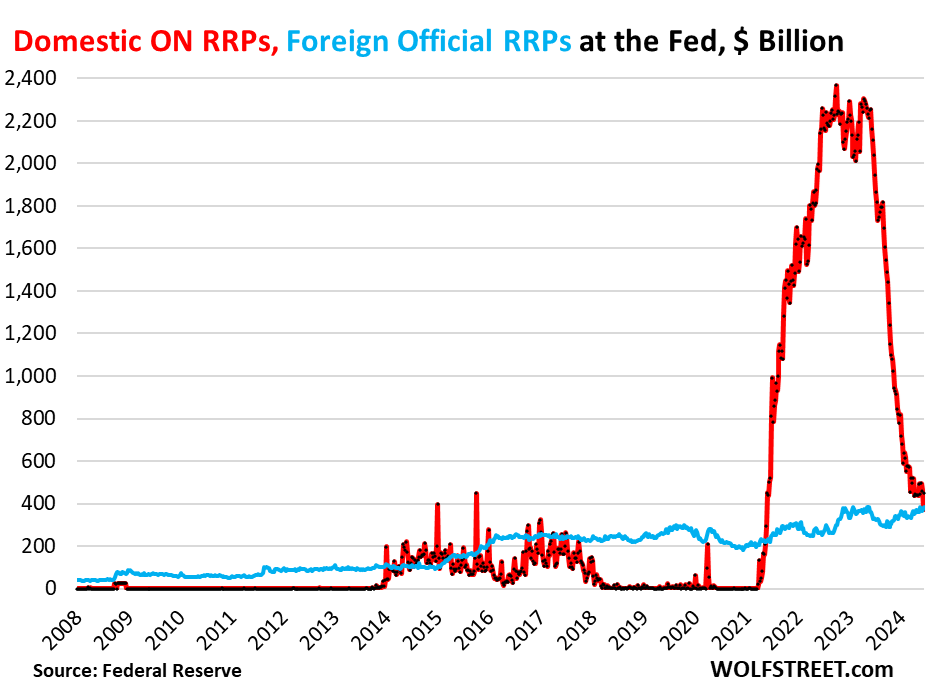

ON RRPs: -$1.92 trillion from peak, to $448 billion. This is where the $1.71 trillion in QT has come out of. And the remainder ($0.2 trillion) has shifted from ON RRPs to reserves.

The Fed offers ON RRPs to domestic counterparties and currently pays 5.3% interest on them. They have been used mostly by money market funds. Other approved counterparties are banks, government-sponsored enterprises (Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, etc.), the Federal Home Loan Banks, etc.

ON RRPs represent excess cash that money markets don’t know what else to do with. ON RRPs have existed for decades, but in normal times, they’re zero or near zero. And now they’re going back toward their normal level:

The three liabilities not affected by QE/QT:

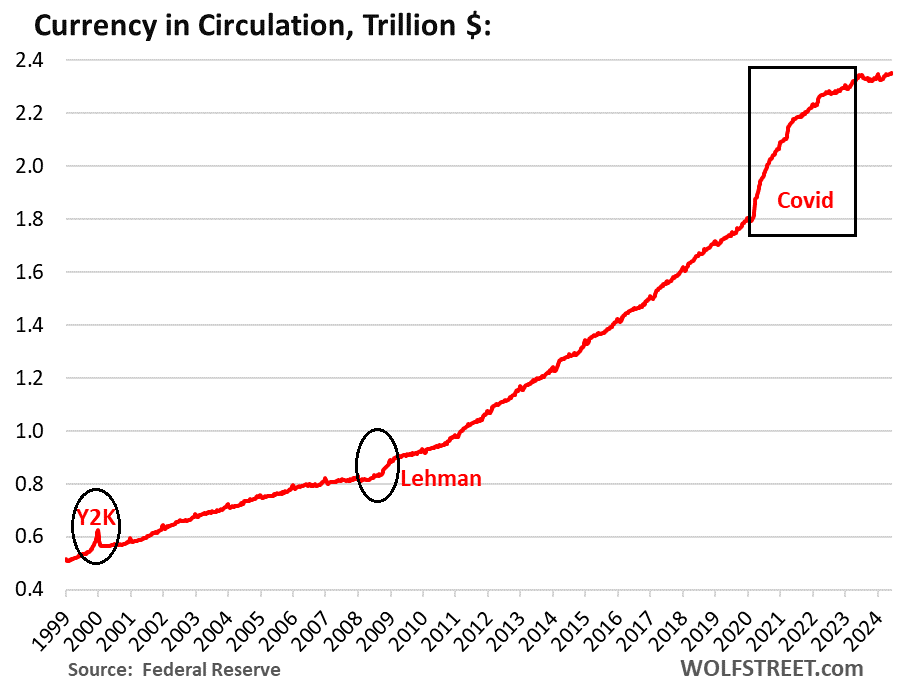

Currency in circulation: $2.35 trillion. These “Federal Reserve Notes,” as it says on each of the bills, are in wallets and under mattresses in the US and globally. It’s entirely demand-based: When customers demand currency, the banking system must have enough on hand. Foreign banks have relationships with US banks to get US currency for their customers.

Banks get the currency from the Fed in exchange for collateral, such as Treasury securities, with the effect that the Fed’s interest-earning assets increase with currency in circulation dollar for dollar.

In other words, when you withdraw $100 cash from an ATM, the Fed gets your $100 in exchange for some pieces of paper that pay no interest, and it invests your $100 and earns interest on it. This interest income from seigniorage used to be the way with which the Fed (and other central banks) financed their own operations and then remitted the remaining profits to the government.

Demand for currency soars during uncertain times, such as Y2K, the months after the Lehman bankruptcy, and Covid. From February 2020 through June 2023, currency in circulation had surged by 30%.

But for the past 12 months, currency in circulation has been little changed: $2.352 trillion on the Fed’s balance sheet today, versus $2.346 trillion at the end of June 2023.

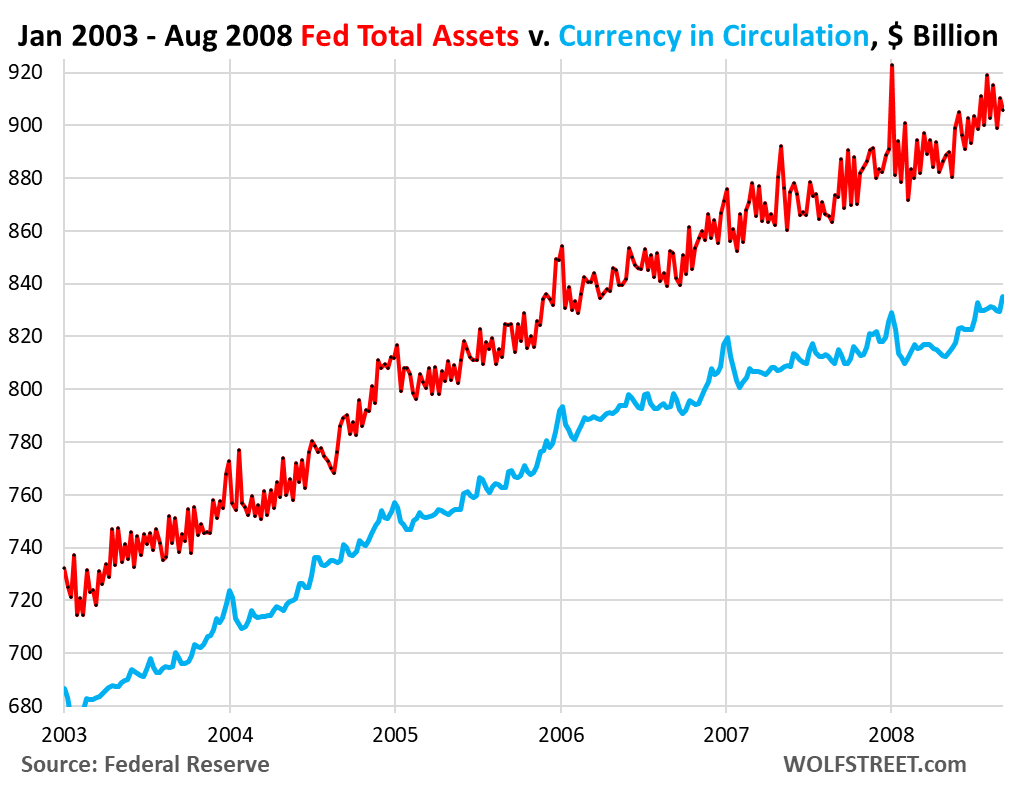

Before 2008: Currency used to be the main factor in increasing the size of the Fed’s balance sheet until 2008, when QE and the addition of the TGA ballooned the Fed’s balance sheet beyond recognition.

Between 2003 and August 2008, just before QE started, the Fed’s total assets rose by 26%, or by $190 billion, from $720 billion at the beginning of 2003, to $910 billion in August 2008. Over the same period, currency rose by 23%, or by $155 billion.

Total assets (red) are so jagged because the Fed used overnight repos to provide liquidity to, or drain liquidity from the banking system via its SRF. But the vast majority of the Fed’s total assets were Treasury securities that grew steadily as a result of growing currency in circulation (blew).

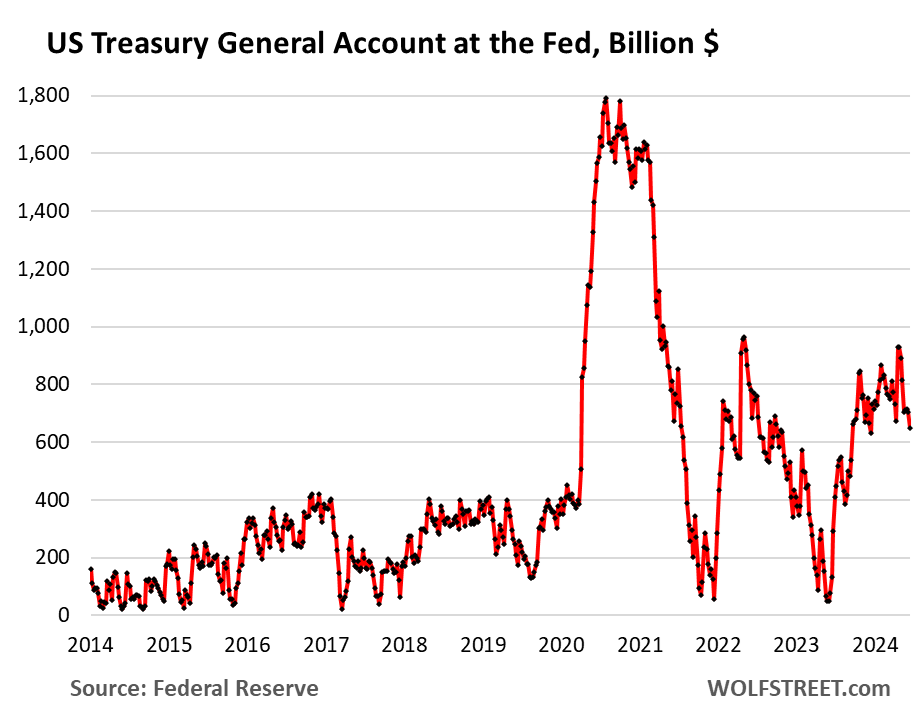

Treasury General Account (TGA): $650 billion. The Treasury Department’s checking account at the New York Fed has massive daily inflows from its Treasury auctions, tax collections, tariffs, fees, etc., and massive daily outflows to pay for what the government spends.

During periods when debt sales are limited by a debt-ceiling fight in Congress, the TGA gets drawn down to scary low levels, at which point the debt ceiling fight is resolved, and the government issues a lot of T-bills to bring the TGA back up to operational levels.

The TGA is not influenced by QT or QE, but by the Treasury Departments management of the government’s finances (cumulative inflows minus outflows).

The governments checking accounts used to be with regular banks, primarily JP Morgan, but during the Financial Crisis, the government moved it from the banks to the New York Fed, so if these banks collapsed, it wouldn’t take down the government’s ability to pay its bills.

RRPs with foreign official counterparties: $385 billion. The Fed offers reverse repurchase agreements to “foreign official” accounts, where other central banks can park their dollar cash. The account balances are determined by decisions of foreign central banks and are not a result of QE or QT.

The chart shows both, ON RRPs with domestic counterparties (red) and RRPs with foreign official accounts (blue). ON RRPs will go to zero or near zero as QT progresses; while foreign official RRPs will keep doing their thing.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()