Status of US Dollar as Global Reserve Currency: Central Banks Diversify from USD-Assets to Other Currencies and to Gold

Long, slow erosion of the US dollar’s dominance. China’s renminbi keeps losing ground, many other currencies gain, as does gold.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

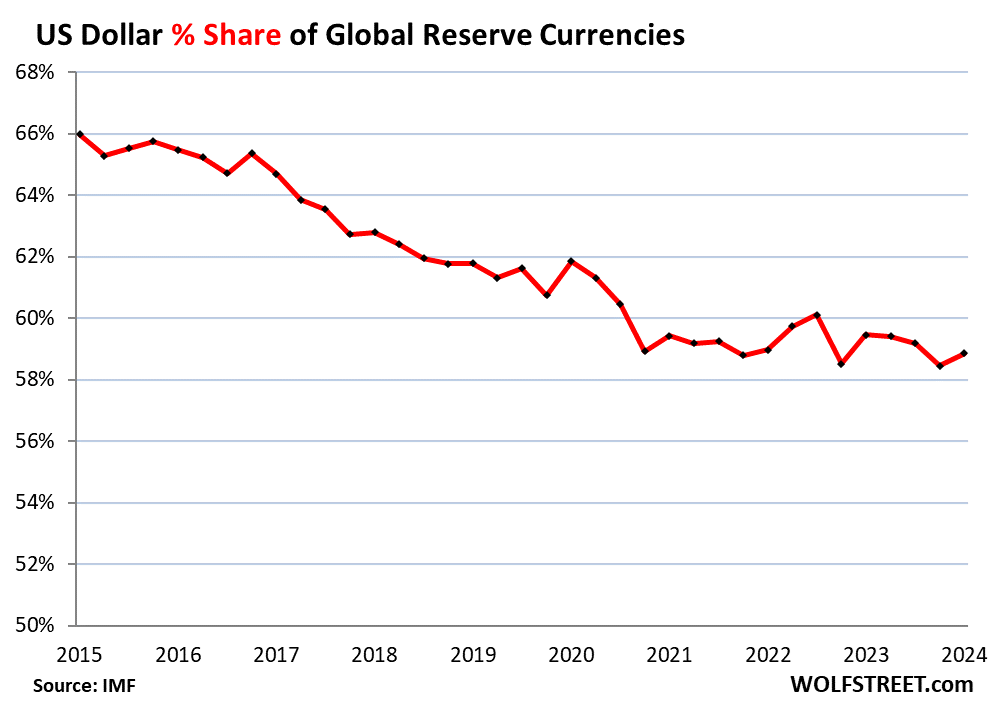

The US dollar is still by far the most dominant global reserve currency, among many reserve currencies held by central banks, but its share has been eroding for years, as central banks have been diversifying to other reserve currencies, and also to gold. But the process is slow and uneven.

The share of USD-denominated foreign exchange reserves ticked up to 58.9% of total exchange reserves in Q1, from 58.4% in Q4, which had been the lowest share since 1994, according to the IMF’s COFER data released on Friday for Q1 2023.

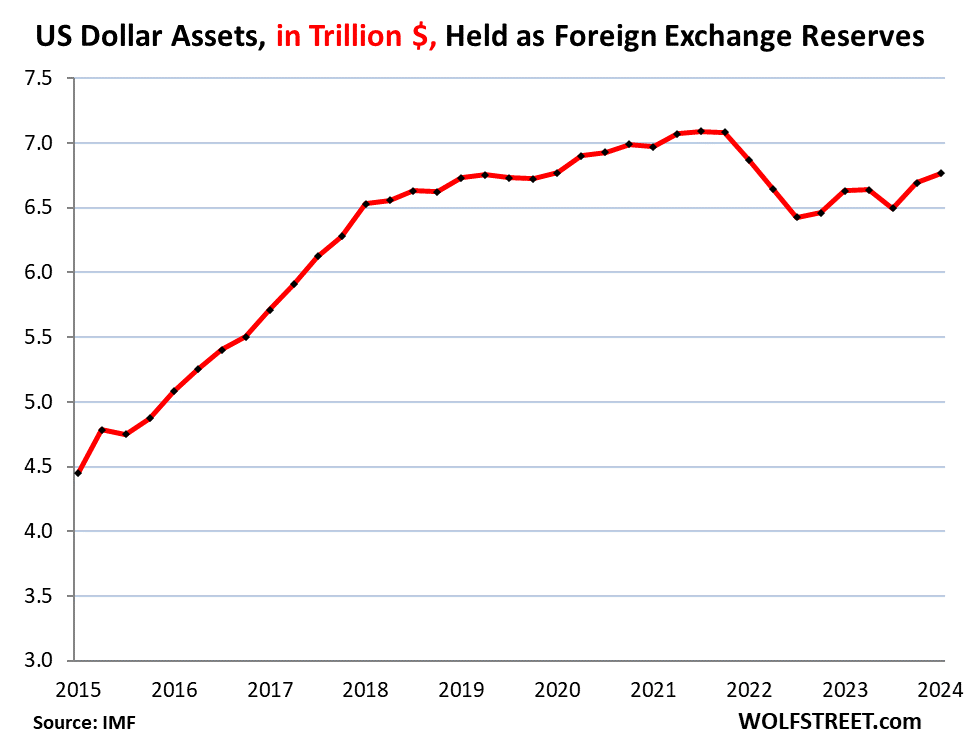

Central banks held total foreign exchange reserves in all currencies of $12.3 trillion in Q1. This included $6.77 trillion in US-dollar denominated assets, such as US Treasury securities, US agency securities, US government-backed MBS, US corporate bonds, even US stocks.

Excluded are any central bank’s holdings of assets denominated in its own currency, such as the Fed’s holdings of Treasury securities and MBS, and the ECB’s holdings of euro-denominated assets.

In dollar terms, holdings of USD-denominated assets at foreign central banks rose to $6.77 trillion in Q1.

It’s not that central banks are “dumping” their dollar-assets – in dollar amounts, their dollar-holdings haven’t changed all that much. It’s that they take on assets denominated in many alternative currencies, and as overall foreign exchange reserves grow, the dollar’s share of the total shrinks.

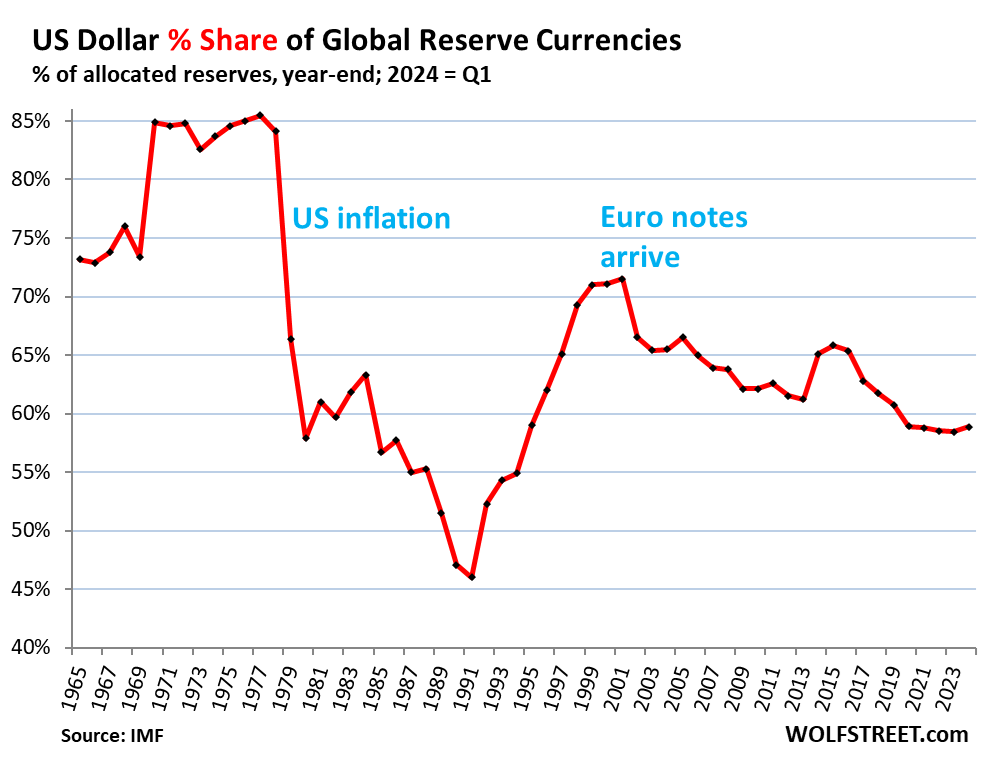

The USD’s share of global reserve currencies has seen a lot of turmoil between 1978 through 1991, when the share collapsed from 85% to 46%, after inflation exploded in the US in the late 1970s, and the world lost confidence in the Fed’s ability or willingness to get this inflation under control.

By the 1990s, confidence returned, and central banks loaded up on dollar-assets again, until the euro came along (share at the end of the year, except 2024 = Q1)

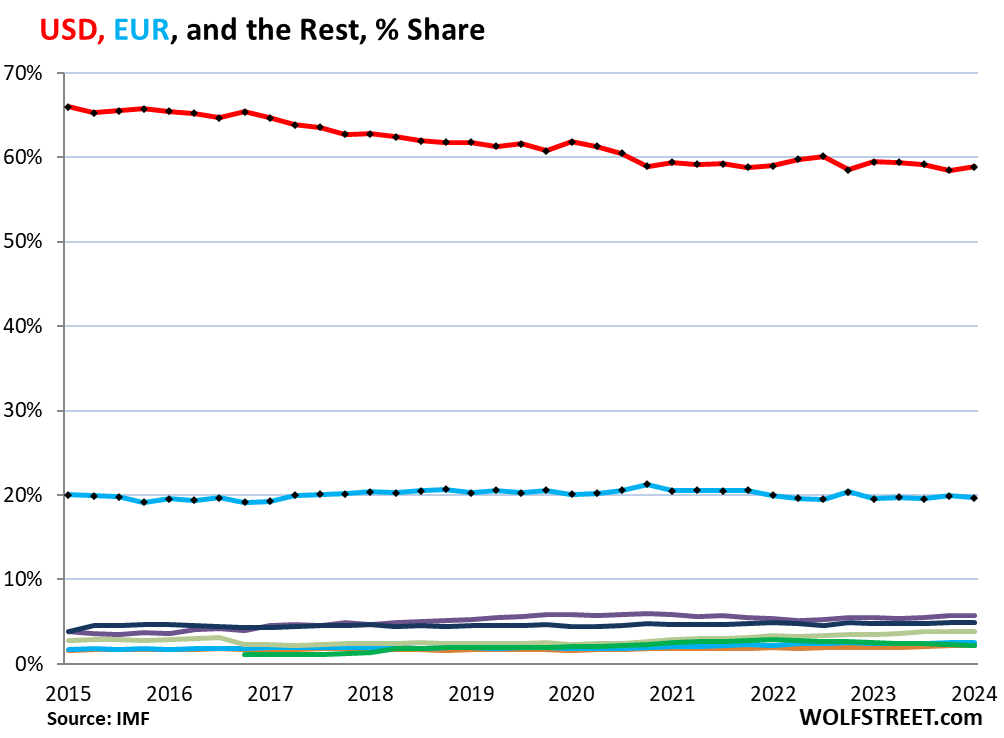

The other major reserve currencies.

The euro is #2, with a share of 19.7% in Q1. The share has been around 20% for years (blue line in the chart below). The other currencies are the colorful tangle at the bottom of the chart.

What’s hard to see in this chart, but easy to see in the next chart, which holds a magnifying glass over the colorful tangle at the bottom, is that these other currencies, except for the Chinese RMB, have been gaining share, while the dollar has been losing share, and the euro’s share has remained stable. It’s not one currency that’s gaining against the dollar; it’s that a lot of “nontraditional reserve currencies,” as the IMF calls them, are gaining share.

The rise of the “nontraditional reserve currencies.”

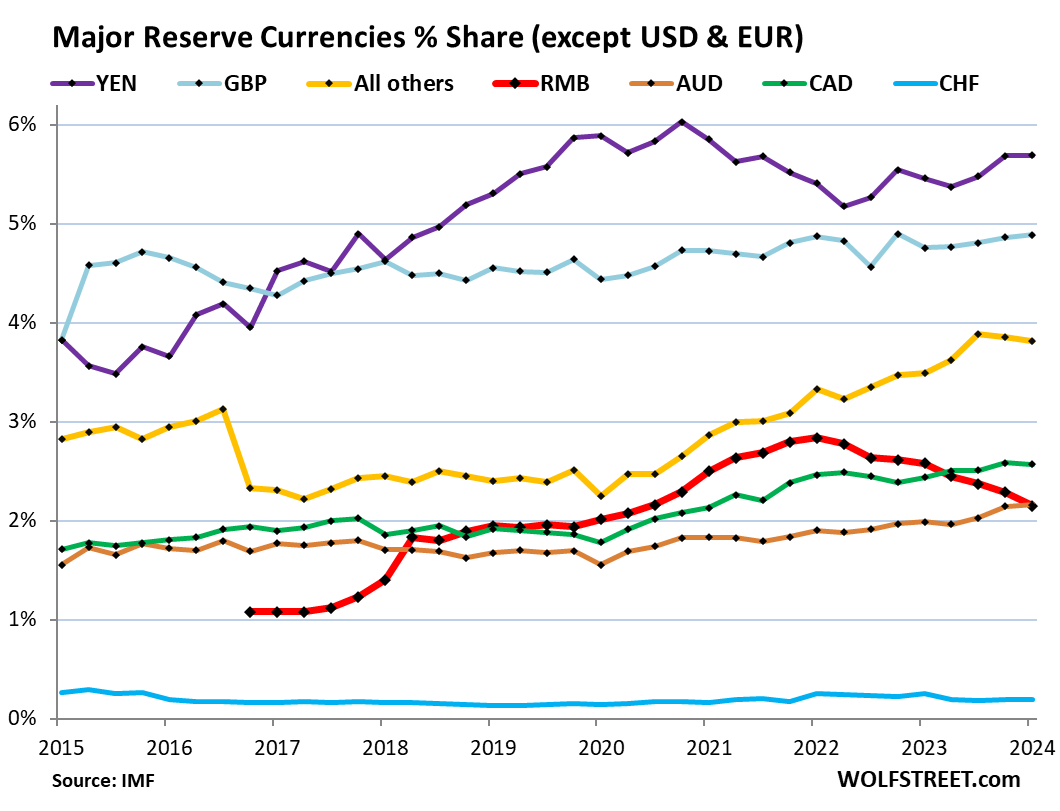

The chart below shows the other currencies magnified. And their shares of the total have been rising over the years.

The exception is the Chinese RMB. China is the second largest economy in the world, yet its currency plays only a small and declining role as a reserve currency. When the IMF, in 2016, added the RMB to its basket of currencies backing the Special Drawing Rights (SDR), many had thought that the RMB would quickly become a threat to the dominance of the USD as global reserve currency. But that has turned out to be not the case.

Depicted in the chart below, by their % share of total foreign exchange reserves in Q1 2024:

- Japanese yen, 5.7%, third largest reserve currency behind USD and EUR (purple).

- British pound, 4.9%, fourth largest reserve currency (blue).

- “All other currencies” combined, 3.8% (yellow). The RMB used to be part of this group. But in 2016, when the RMB joined the SDR basket, the IMF began showing it separately, and as a result of the separation, the share of “other currencies” dropped by the RMB’s share. After that separation, “all other currencies” without the RMB had a share of 2%. This has grown to 3.8% by Q1.

- Canadian dollar, 2.6% (green).

- Chinese renminbi, 2.1%, lowest since Q2 2020, 8th quarter in a row of declines (red), amid capital controls, convertibility issues, and other issues. Central banks appear to be leery of holding RMB-denominated assets.

- Australian dollar, 2.2% (brown).

- Swiss franc, 0.2% (blue).

The IMF found in a 2022 paper that there were 46 “active diversifiers” – countries that have at least 5% of their foreign exchange reserves in “nontraditional reserve currencies.” The list includes major advanced economies and emerging markets, including most of the G20 economies.

The IMF thought that two major factors contributed to the rise of the “nontraditional reserve currencies”:

- The growing liquidity of markets in those currencies, which makes it easier to trade those assets.

- Chasing higher yielding assets elsewhere during the 0%-era in the US and Europe.

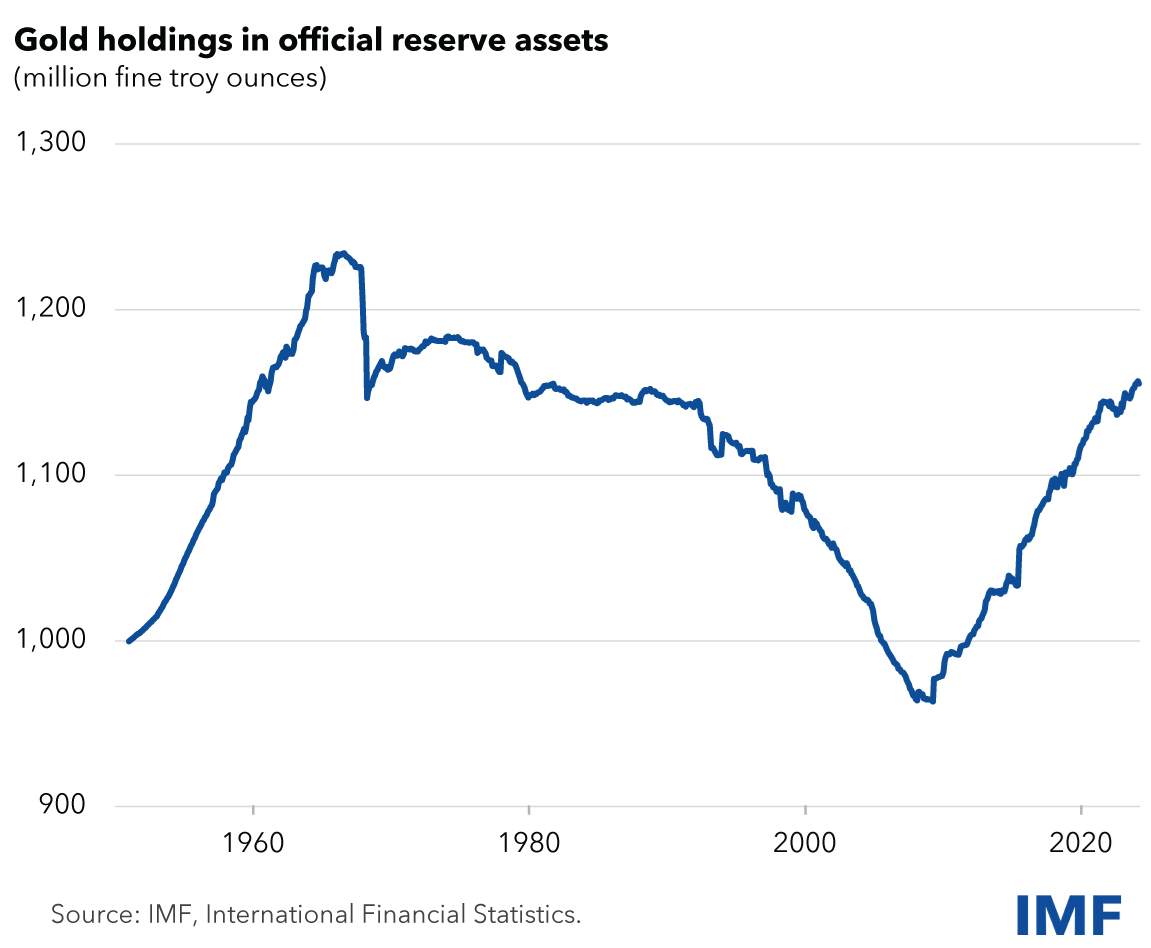

The rise of gold as central bank reserve asset.

Gold bullion is not a currency and is not included in “foreign exchange reserves” of central banks – the data above.

But bullion holdings are in the overall “reserve assets” of central banks. And central banks, after spending decades shedding their holdings, have been rebuilding them for the past decade. According to the IMF, they’re currently at 1.16 billion troy ounces – roughly $2.7 trillion, compared to $12.3 trillion in foreign exchange reserves (chart via the IMF):

USD-exchange rates and foreign exchange reserves.

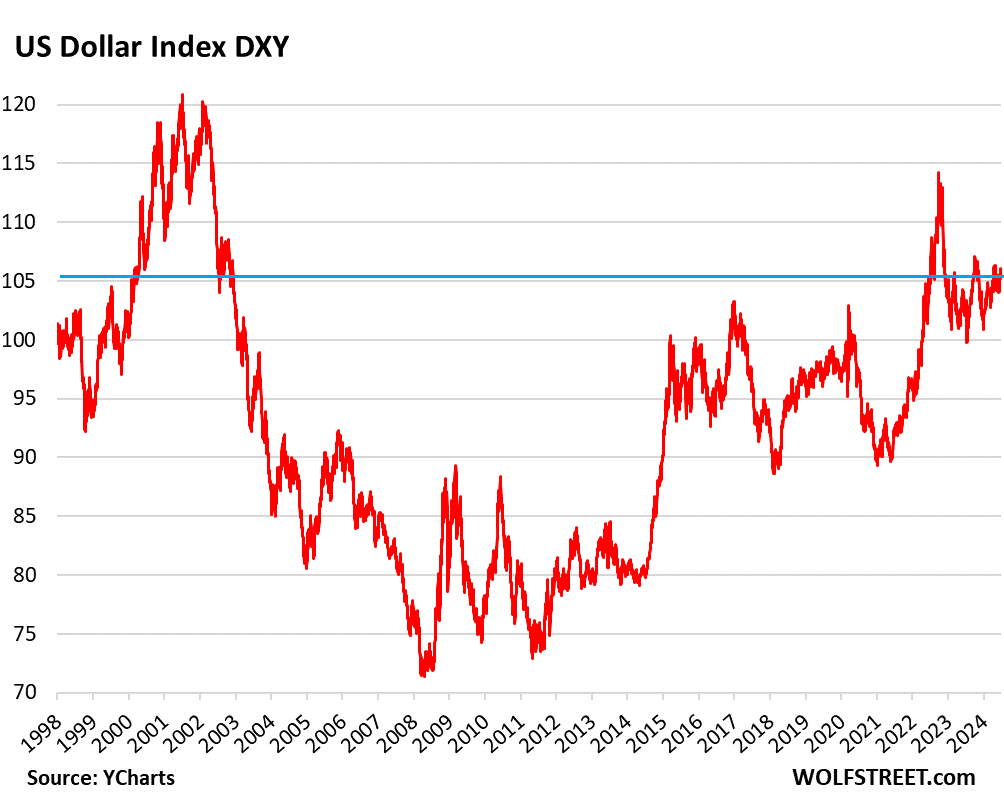

Foreign exchange reserves are reported in USD. USD holdings are obviously reported in USD, and the holdings in EUR, YEN, GBP, CAD, RMB, etc. are translated into USD at the exchange rate at the time. So the exchange rates between the USD and other reserve currencies change the magnitude of the non-USD assets – but not of the USD-assets.

For example, Japan’s holdings of USD-denominated assets are expressed in USD, and they don’t change with the YEN-USD exchange rate. But its holdings of EUR-denominated assets are translated into USD at the EUR-USD exchange rate at the time. So the magnitude of Japan’s holdings of EUR-assets, expressed in USD, fluctuates with the EUR-USD exchange rate, even if Japan’s holdings don’t change.

Exchange rates fluctuate wildly. But over the long run, the Dollar Index [DXY], which is dominated by the euro and yen, is back at 101, where it had been in 1999 (data via YCharts):

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()