How George Soros Broke The British Pound And Why Hedge Funds Probably Can’t Crack The Euro

Greek citizens voted against further austerity measures demanded by the Troika financing their rescue package, casting even more doubt on the country’s future as a member of the eurozone and throwing bond and currency markets into an uproar.

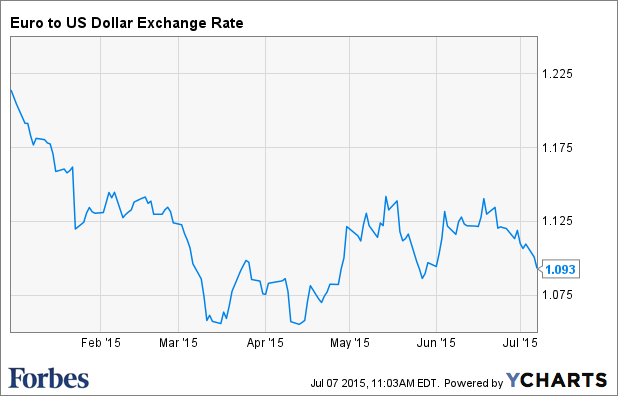

The euro has plunged from $1.20 to $1.09 this year (see chart). The feared unraveling of the currency – which, admittedly, would take a lot more than Greece’s departure – calls to mind another currency fiasco from the early 1990s, when George Soros and a group of other investors that included fellow hedge fund managers Paul Tudor Jones and Bruce Kovner, bet against a central bank’s ability to hold the line on its currency.

Euro to US Dollar Exchange Rate data by YCharts

Forbes took a deep dive into that trade in the November 9, 1992 issue, illuminating how Soros made $1.5 billion in just a single month by betting the British pound and several other European currencies were priced too richly against the German deutsche mark.

The entire group cashed in big-time. Jones’ funds made $250 million, while Kovner’s Caxton Corp. rang the register to the tune of $300 million, but no one made more than Soros, who cleared $1.5 billion in that fateful month of September. (The score made Soros’ legend and swelled his firm’s coffers; assets under management jumped to $7 billion, from $3.3 billion, by mid-October 1992, and to $11 billion by the end of 1993.)

“They bet that the politicians and central banks could not much longer maintain artificially high exchange rates in the interests of European unity,” wrote authors Thomas Jaffe and Dyan Machan.

The inverse is apt these days, with many traders questioning how European leaders can possibly maintain their tenuous grip on exchange rates and bond yields in the eurozone, where several nations boast 10-year bond yields well below those of the U.S., which at least controls its own currency.

One thing that is clear is the stakes have only gone up since 1992. From Jaffe and Machan’s story (republished in full below):

In former times, powerful central bankers could usually frustrate speculators. They did so by simply buying massive amounts of the weaker currency and flooding the market with the stronger currency. But times are changing. While the central banks can mobilize tens of billions of dollars, trading in foreign currency markets now runs to a trillion dollars a day.

Foreign currency trading has only gotten more massive – pegged at over $5 trillion a day by the Bank for International Settlements – but so has the financial firepower of central banks. The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet stands at $4.5 trillion after years of quantitative easing, while the European Central Bank laid out a plan for 1.1 trillion euro of bond purchases through September 2016.

That makes the sums Soros was betting against seem almost pedestrian by comparison.

So could a repeat of the Soros score happen today?

Traders can certainly position to profit if the euro currency unravels, but Soros’ bet benefited from the insular nature of the Bank of England in the early 1990s.

“The world is a lot smaller than it was in 1992,” says Dean Popplewell, vice president of currency analysis at foreign exchange currency Oanda. “Central banks today work much more quickly and collectively than in years past, to avoid knock-on effects.”

The last decade offered plenty of lessons in how rapidly a crisis can emerge, from the collapse of 2008 to the European sovereign debt mess that is still roiling financial markets. Central banks have moved to the forefront, far more transparently telegraphing their actions. While there can be isolated instances of breakdowns — the Swiss National Bank’s surprise withdrawal of its euro peg in January was far more reminiscent of 1992 than anything happening in the euro — trading has remained largely fluid and orderly, Popplewell says, pointing to the recent spike in German bund yields that was significant, but quickly absorbed by the market.

Fed policy is also a crucial element in the euro story, since interest rate divergence is what helped make Soros’ trade a winner in 1992. Were it only considering U.S. conditions, the Fed would likely raise rates at least once and probably twice this year, Popplewell suggests, but it’s clear Janet Yellen and her central bank colleagues have a more global perspective that takes into account the stronger dollar, Europe’s struggles and the peril looming if the overheated Chinese stock market collapses. If those concerns keep a leash on Fed rate hikes, the bets on its policy diverging with that of the ECB will take longer to pay off.

Will traders make money if the euro falls to parity with the dollar or below? Of course. A host of macro-focused hedge funds are said to have short euro positions. But are any loading up the truck like Soros did, with a variety of long and short positions designed to make billions on the currency’s collapse? The odds on that bet are probably a bit longer.

How The Market Overwhelmed The Central Banks

November 9, 1992: By Thomas Jaffe and Dyan Machan

Here’s one for the “Guinness Book of World Records”: Though the world is chock-a-block with billionaires, George Soros may be the first person to make over $ 1 billion in the span of a single month. That’s right: one month.

SEPTEMBER 1992 was a month international money managers won’t easily forget. Especially George Soros, the legendary chairman of the Quantum group of funds. Soros and clients of his four Netherlands Antilles-domiciled pools cleared a cool $ 1.5 billion in just one month as a result of the upheaval in Europe’s markets. Nor is that all the Soros crowd has made this year: Between the end of August and earl October the new asset value of his flagship $ 3.3 billion (assets) Quantum Fund rose 31%, and it is up 51% year-to-date. As of mid-October his assets under management had swelled to $ 7 billion.

There were other big winners in the currency turmoil that toppled the pound sterling, the lira and other soft European currencies and humbled the central banks of Europe. The big winners include Bruce Kovner of Caxton Corp. and Paul Tudor Jones of Jones Investments. Kovner’s funds made an estimated $ 300 million, increasing assets to about $ 1.6 billion; Jones’ funds were up some $ 250 million, to $ 1.4 billion in assets.

The month of wild trading and sheer excitement that wrecked the European Exchange Rate Mechanism were also good times for leading U.S. banks with big foreign exchange operations, especially Citicorp, J. P. Morgan, Chemical Banking, Bankers Trust, Chase Manhattan, First Chicago and BankAmerica. Together, in the third quarter, they netted before taxes over $ 800 million more than what they normally earn in a quarter from trading currencies.

What did these people do to make so much money? They bet on the inevitable. They bet that the pound and the other weaker European currencies were overpriced against the deutsche mark. They bet that the politicians and the central banks could not much longer maintain artificially high exchange rates in the interests of European unity.

Europe’s Exchange Rate Mechanism was set up in 1979 by the then-members of the European Economic Community to keep the various European currencies relatively stable against one another. Relatively narrow fixed trading ranges were established within which the prices of 11 European currencies were supposed to fluctuate. But the system could work only if the various countries coordinated their economic policies. In one nation had, say, higher inflation than another, there would be great strain on the system. Differences in interest rates also would strain the system. When differences in interest rates and inflation rates among the 11 got out of line, the central banks had to intervene to buy and thus support the weakening currency against speculators and currency hedgers.

In former times, powerful central banks could usually frustrate speculators. They did so by simply buying massive amounts of the weaker currency and flooding the market with the stronger currency. But times are changing. While the central banks can mobilize tens of billions of dollars, trading in foreign currency markets now runs to a trillion dollars a day.

Andrew Weisman, director of currency fund management for French bank Credit du Nord, makes no apologies for the speculative operations mounted by his and other banks against the fixed rates. “The central banks brought September’s debacle upon themselves,” he asserts. Why does he say this? Because the exchange rates they were defending may have made political sense for the European leaders committed to the European Community but no longer made any economic sense.

Soros and the others who won big when the market overwhelmed the banks were mostly involved in one variation or another on a basic technique: Go short the weakest currencies. Going short a currency can be done in a number of ways. The simplest is simply to borrow money, say, Italian lire, and convert the borrowed money into, say, deutsche marks at the fixed rates. Then you wait for the lira to drop sharply against the DM, buy in the now cheaper lira to repay your debt and pocket a lot of extra deutsche marks.

In September the lira was trading at 765 lire to the mark. Four weeks later it took 980 lire to buy a single DM. A speculator who had performed this operation would have made a profit equal to 28% of the borrowed sum.

But his profit would have been much more than 28%. Speculators with substantial credit lines like Soros can borrow on a margin of 5% and get 20-to-1 leverage. That means you can borrow $ 1 billion for speculation by putting up just $ 50 million in cash. The result: Instead of having made 28% on your lira bet, you would have made 560%, or $ 280 million.

There are other ways, of course, to play the currency markets: through futures and options, for example. Soros actually evolved a complex play.

George Soros generally avoids the press, and in this moment of great triumph, he is as elusive as ever. But it is clear that he had concluded the European central banks were holding lousy hands in their game against the speculators and hedgers. That’s why he was willing to bet the ranch.

Though Soros would not talk with FORBES, his spokesman did. He told us Soros has expected financial turmoil in Europe ever since the Berlin Wall collapsed in November 1989, leading to the reunification of Germany. These events, thought Soros, would doom the Exchange Rate Mechanism.

A Soros spokesman explains: “To have one [pan-European] currency and make it stick, you need one economy. But when one country was booming because it had essentially done a leveraged buyout of East Germany, while the others were in a recession, this made it inappropriate for the others to rely on Germany’s monetary policy in trying to maintain their own currencies.”

After German reunification, in Soros’ view, it was only a matter of time before the European Exchange Rate Mechanism came unglued.

By this year it was clear to just about everyone that some European currencies — the British pound and Italian lira, for example — were fundamentally overvalued in relation to stronger ones such as the deutsche mark and French franc. As Britain and Italy struggled to make their currencies attractive, they were forced to maintain high interest rates to attract foreign investment dollars. But this crimped their ability to stimulate their sagging economies. While the British and Italians tried to deal with weak economies, Germany embarked on a policy of trying to restrain its own economy, overstimulated by the spending on eastern Germany.

There were plenty of players beside George Soros betting against the central banks and the ERM. Foreign exchange traders at money center banks and investment banks like Goldman, Sachs are constantly aware of what is happening in the international money markets. When large institutions, mutual funds and multinational corporations that do massive currency hedging to protect their profits started selling the weaker European currencies in September, the traders immediately picked up on the jump in volume they were handling for their customers. They could easily estimate just how great the selling pressure was and how much the central banks would have to spend to prop up those currencies. Then, the banks and investment houses got into the game for their own accounts.

It was obvious, for instance, that the Bank of England wouldn’t be able to support the pound successfully, so the banks started to use their own capital to heavily sell the currency short. Some of the more aggressive, like Citicorp and Bankers Trust, made roughly an extra $200 million apiece pretax from the trading turmoil in September. And it may have been even more. But the magnitude of these gains won’t show up in the third quarter’s results. When trading profits are that large, the banks often roll them over into succeeding quarters to minimize their tax bill.

We mentioned that Soros played a complex game. Here’s how it went. Soros expected the following: the breakdown of the ERM and a substantial realignment of European currencies; a dramatic drop in European interest rates; a decline for European stock markets.

So, rather than simply shorting the weak currencies, he also placed simultaneous bets on interest rates and securities markets that would be affected by the currency realignments.

In carrying out this operation, Soros and his aides sold short sterling to the tune of about $ 7 billion, bought the mark to the tune of $ 6 billion and, to a lesser extent, bought the French franc. As a parallel play they bought as much as $ 500 million worth of British stocks even while they were shorting sterling, figuring that equities often rise after a currency devalues. Soros also went long German and French bonds, while shorting those countries’ equities. Soros’ reasoning on the French and German markets was that upward valuation was bad for equities but was good for bonds because it would lead to lower interest rates.

“When the Italians finally devalued the lira and the Germans lowered rates slightly,” says the Soros spokesman, “it was almost like we’d been preparing for an exam for six months and now were finally taking our test.”

After the lira was battered, Soros read that Helmut Schlesinger, president of the Bundesbank, had openly stated that Germany’s central bank would not go to the wall for the pound. Soros has said that he saw this as a “clarion call for everyone to get out of sterling.”

Because of his strong credit, Soros was able to maintain all these positions with just $ 1 billion in collateral. He was margined to the eyebrows, but he wasn’t really gambling. “The profits that people like Soros recently made seem astronomical,” says Gilbert de Botton, chief of London’s $ 5-billion-plus (assets) Global Asset Management. “But do not rap them on the knuckles on one of the few occasions where they actually could make money. Even the pros have lost their shirts from time to time because of the absolute power of the central banks.”

Soros knew this, but all his experience, all his instincts told him that this time he was betting with odds overwhelmingly in his favor.

Here’s how his leveraged positions worked out: The pound dropped 10%, the mark and franc both rose roughly 7%, the London stock market gained 7%, German and French bonds were up about 3% apiece, and the German and French stock markets briefly rallied, but basically remained flat.

FORBES has learned that since early October Soros has substantially decreased the size of his hedge. He has bought pounds and sold marks to cover most of his short position in sterling. But Soros is still holding on to his British stocks, and continues to be bullish on European bonds. Soros sees interest rates dropping in Europe and thinks that the Continent is headed into a deep recession.

He has taken no pride in being referred to as the man who beat the central banks. One money manager who knows Soros well says: “George actually wants to be perceived as helping central bankers.”

Was betting against them being helpful? In the sense that he was essentially betting on the inevitable, maybe yes.

The volatility in European currencies continues. Soros and other shrewd investor will no doubt continue trying to profit off the turbulence. But it will be a long time before a chance to make a killing like this year’s appears again.