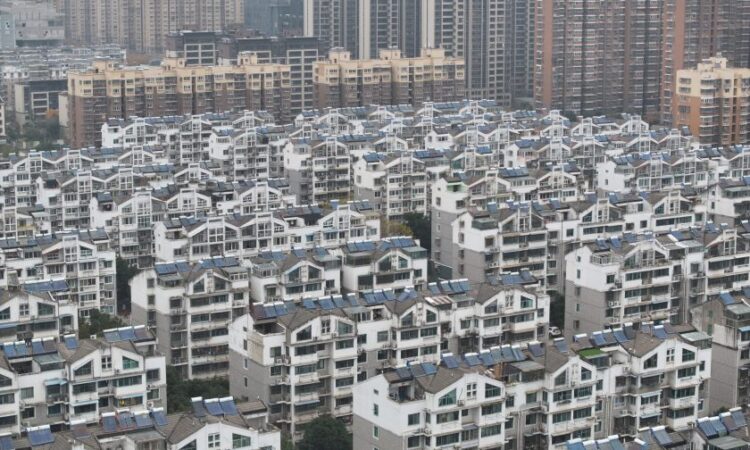

Residential houses in Nanjing, East China’s Jiangsu Province, last month. Costfoto/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Chinese stocks just capped another dismal week, with a gauge of mainland firms listed in Hong Kong languishing at the bottom of global equity index rankings for the year so far.

Grim milestones have kept piling up in recent days: Tokyo has overtaken Shanghai as Asia’s biggest equity market, while India’s valuation premium over China has hit a record. Locally, a meltdown in Chinese shares is wreaking havoc on the nation’s asset management industry, pushing mutual fund closures to a five-year high.

The Hang Seng China Enterprises Index has already lost 11% in 2024. Coming after a record four-year losing streak, the slump is reinforcing a structural shift that’s seeing everyone from active money managers to passive funds turn their back on the world’s second-largest stock market.

The Nasdaq Golden Dragon China Index slipped as much as 2.2% at the start of US trading Friday, extending losses to a fifth consecutive day.

In all, some $6.3 trillion has been wiped out from the market value of Chinese and Hong Kong stocks since a peak reached in 2021, underscoring the challenge that Beijing faces as it seeks to arrest a decline in investor confidence. Authorities have ruled out the use of massive stimulus to revive the flagging economy, leaving traders wondering when things will improve.

“What we are seeing this year so far really is a continuation of what we saw last year,” John Lin, AllianceBernstein’s chief investment officer of China equities, said in an Jan. 17 interview on Bloomberg Television. “These squeezing-the-toothpaste type of stimulus policies so far haven’t been able to turn around the underlying bottom-up fundamentals of areas like the property sector.”

‘Waiting Game’

The HSCEI gauge plunged more than 6% this week and is on track to record its worst January performance in eight years. On the mainland, the CSI 300 Index has dropped in nine of the last 10 weeks. Signs that state funds likely bought exchange-traded funds and a decision by China’s largest brokerage to suspend short selling for some clients failed to halt the onshore benchmark’s losing run.

The headwinds buffeting the market are well documented: China’s real estate sector remains a trouble spot, deflationary pressures are building and a long-running feud between Beijing and Washington refuses to go away, with the US election set to take place later this year. In recent days, uncertainties about the trajectory of US interest rates and the threat of an imminent blowout of local stock derivatives have added to investor worries.

Asian fund managers have cut their allocation to China by 12 percentage points to a net 20% underweight, the lowest in more than a year, according to the latest Bank of America survey.

Managers of benchmark-tracking funds have sold a net $300 million of shares traded in mainland China and Hong Kong this month, according to a Morgan Stanley analysis. That’s a reversal from the last half of 2023, when they bought $700 million on a net basis even as stock indexes declined.

“China is a waiting game and we continue to be waiting,” said Mark Matthews, head of Asia research at Bank Julius Baer & Co., which is mostly avoiding Chinese equities.

Beijing’s efforts to reassure investors have been met with skepticism from investors, many of whom worry that authorities are behind the curve. While the People’s Bank of China took steps last month to pump cash into the financial system, it bucked widespread expectations for cutting a key policy rate on Monday.

Speaking to leaders at the World Economic Forum this week, Chinese Premier Li Qiang trumpeted his nation’s ability to hit its roughly 5% growth target for 2023 without flooding the economy with “massive stimulus.”

Right now, the loss of confidence is so severe that even attractive valuations are of little help. The MSCI China Index has never been this cheap versus the S&P 500 gauge from a forward earnings estimate perspective. Still, bets on a short-term rebound have failed to materialize.

“The government seems very sanguine about the economy,” said Xin-Yao Ng, an investment director for Asian equities at abrdn. “The market might not even trust the 5% growth figure, it certainly has a much more negative view on the economy and definitely believes Beijing needs a big fiscal response.”

— With assistance from Sangmi Cha, April Ma, Hideyuki Sano, Carmen Reinicke, and Cristin Flanagan