Quinnipiac University has put itself on the map in recent years — literally. Over the last five years, the private Connecticut university has poured tens of millions of dollars into offshore hedge funds.

Public tax records indicate that Quinnipiac has maintained a multimillion-dollar investment portfolio in the Cayman Islands — where lenient corporate tax laws enable investors to avoid paying taxes on their offshore assets — since at least 2018.

Quinnipiac’s most recent financial audit valued its hedge fund investments at $48.4 million as of June 2023.

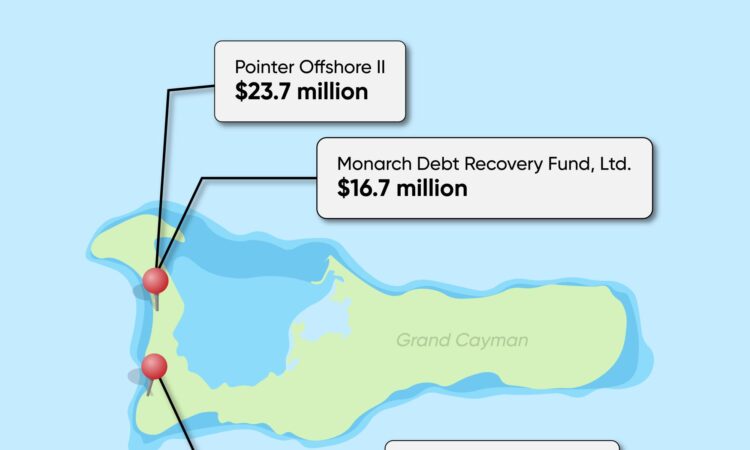

More than a third of those assets — $16.7 million — are tied up in Monarch Debt Recovery Fund Ltd., one of some two dozen hedge funds operated by multibillion-dollar pooled investment fund manager Monarch Alternative Capital.

And despite Quinnipiac’s public commitment to “outcomes that support the long-term sustainability of our planet,” Monarch Alternative Capital’s filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission show that the corporation bankrolls the fossil fuel and tobacco industries.

As of 2019, Monarch owns a 4.33% stake in Arch Resources — a $3.2 billion coal mining and processing company — worth more than $104 million.

Monarch is also a majority owner of Pyxus International, a $1.6 billion tobacco distributor. The New York City-based corporation’s 24.6% ownership stake in Pyxus is worth more than $11 million.

And back in 2018 — the first year Quinnipiac disclosed its ties to Monarch — the corporation had more than $90 million invested in oil and gas acquisition company Resolute Energy and crude oil shipping company Gener8 Maritime. Both corporations have since been bought out.

“Quinnipiac does not have any direct investments in fossil fuels and has committed to not investing directly in fossil fuel interests,” wrote John Morgan, associate vice president for public relations, in a statement to The Chronicle Tuesday.

But by investing in Monarch, the university is banking on the success of Monarch’s portfolio. So, while Quinnipiac may not be directly investing in fossil fuels, the university’s multimillion-dollar stake in Monarch’s pooled investments ensures it profits from the industry’s success.

“Some commingled funds in our portfolio, which are funds that invest in a wide array of companies and industries, may include fossil fuel interests as a portion of the fund,” Morgan wrote. “Investments in commingled funds provide scale, access to leading investment managers and diversification which is vital to growing the endowment for realization of major improvements at the university, and for the long-term success of Quinnipiac University and the communities it serves.”

The university disclosed having another $23.7 million invested in Pointer Offshore II, a Cayman Islands-incorporated hedge fund based in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Pointer’s holdings — unlike Monarch’s — are not public, meaning its SEC filings do not disclose its investments.

Quinnipiac invests the remaining $8 million in Ironwood International, a hedge fund manager overseeing more than $6.8 billion in global assets. Ironwood is technically headquartered in San Francisco. However, it is legally registered as operating out of the Ugland House, a law firm on Grand Cayman that serves as the official address for thousands of supposedly U.S.-based businesses. Ironwood’s holdings are not public.

Because Quinnipiac’s finances are shrouded in mystery, the history of the university’s $48.4 million hedge fund portfolio — today worth what 873 students pay in annual tuition and fees — is murky at best.

Public disclosure requirements rarely apply to private institutions, meaning the university’s financial activities are, as a general rule, not subject to public scrutiny.

But Quinnipiac — like the majority of colleges in the United States — is a not-for-profit institution. And even private nonprofits must file annual returns with the Internal Revenue Service to remain exempt from federal income taxes. This tax return, known as the form 990, is one of the few public insights into the financial activities of private nonprofits like Quinnipiac.

Compared to a public institution’s disclosure requirements, the 990 is relatively limited in scope and only broadly outlines a private entity’s finances.

However, as far as offshore hedge funds go, two relevant figures are subject to disclosure: the value of an institution’s private investments and the value of an institution’s foreign investments.

It was a technicality in the 990 form’s disclosure requirements for private assets — not foreign assets — that forced Quinnipiac to reveal its hedge fund investments in 2018.

For context, the IRS typically only requires institutions to disclose the net value of their private investments, not specifics about the holdings. There is one notable exception: if an institution’s privately held securities comprise more than 5% of its total assets.

Quinnipiac’s $81.9 million in private investments constituted 5.2% of its total assets in fiscal year 2018-19, forcing the university to disclose having $39.8 million of that tucked away in three hedge funds in the Cayman Islands.

A dozen private equity investments accounted for most of the remaining $42.1 million, per the university’s 2018-19 filing. Alternative investment firm Ares Management — whose board of directors Quinnipiac President Judy Olian serves on — acquired one of the private equity firms the university used, Landmark Equity Partners, in 2021. It is unclear if Quinnipiac still holds investments with this firm.

Quinnipiac’s foreign investment practices are quite common in higher education. Public tax filings show that at least five other Connecticut colleges — Fairfield University, Sacred Heart University, Trinity College, Connecticut College and the University of Hartford — maintain multimillion-dollar hedge fund portfolios. In fiscal year 2021-22 alone, these six schools disclosed a combined $288.1 million in hedge fund investments.

But in a different section of Quinnipiac’s 2018-19 filing, the university denied having any foreign investments valued at more than $100,000. In fact, in the decade that the IRS had required organizations to disclose foreign transactions, the university had never once reported investing money outside of the United States.

If not for the IRS’s 5% disclosure threshold, it is possible that Quinnipiac’s offshore investments may never have come to light.

The multimillion-dollar discrepancy calls into question the credibility of Quinnipiac’s previous 990 filings.

To put it another way: for the university’s older disclosures to have been accurate, Quinnipiac would have had to have placed all $39.8 million into those offshore hedge funds between July 2018 and June 2019.

But even Quinnipiac’s own financial statements do not support this hypothetical.

Case in point, the university’s 2018-19 990 filing indicates that its privately held securities only saw an $8.9 million increase in this 12-month timeframe.

And while Quinnipiac’s 2018-19 audit report does not specifically mention the term “hedge funds,” the listed value of one of the university’s so-called “alternative” investments corresponds — to the exact dollar — to the value of its offshore hedge fund assets.

Using that logic to backtrace these assets, it appears that Quinnipiac had held more than $31 million in offshore hedge fund accounts since at least fiscal year 2015-16 — three years before disclosing these investments.

Quinnipiac’s recent tax filings have been more forthcoming about the university’s foreign assets than in the past.

In fiscal year 2019-20, Quinnipiac’s reported foreign transactions totaled $53.7 million and spanned every IRS-defined geographic region except Antarctica and South Asia. Quinnipiac’s 990 filing indicates that the university poured roughly 90% of these funds — $47.5 million — into foreign investment funds located in Central America and the Caribbean. Subsequent filings valued Quinnipiac’s foreign investments in Central America and the Caribbean at $55.1 million in 2020-21 and at $50.5 million in 2021-22.

Quinnipiac’s audit disclosures valued the university’s offshore hedge fund assets at $40.6 million in 2019-20 and $46.1 million in 2021-22 — leaving $6.9 million and $4.4 million in foreign investments unaccounted for each year.

But because private investments constituted less than 5% of Quinnipiac’s total assets in each of these years, the university was not required to publicly disclose any specifics about these investments in its 990 filings.