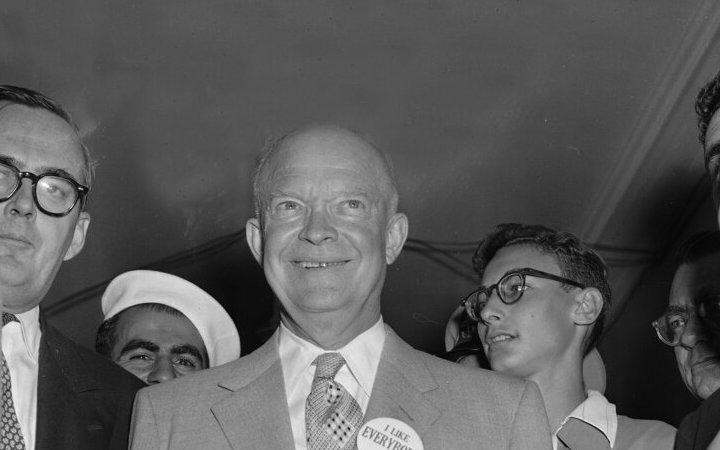

We were delighted to see that Wall Street Journal editorial online today stressing the importance of stable money in the rescue of Argentina under its new president, Javier Milei. It reminds us of what happened in 1952, the last time a Republican presidential nominee — in this case, Dwight Eisenhower — ran on a platform calling for a dollar convertible into gold. It precipitated a debate over the importance of stable money.

We first wrote about this in an editorial headlined “The Last Call.” It was triggered by the appearance on our doorstep one evening by James Grant of the Interest Rate Observer. He was lugging a bound volume of the business journal Barron’s from 1952. A page-one editorial that summer featured the headline “Golden Plank: It’s a Test of Republican Promises.” It weighed the call of the GOP’s presidential platform for a “dollar on a fully convertible gold basis.”

The editorial, and the platform plank, reflected the optimism that year that Eisenhower and Congressional Republicans would restore an honest dollar after some 20 years of devaluation and artificial inflation imposed under the Democrats and FDR. In 1933, FDR took America off the old gold standard. The plank, Barron’s conceded, “reflects a deep and legitimate yearning on the part of the American people for a return to hard money.”

Yet before “a return to the gold standard” could “be contemplated,” Barron’s caviled, “certain great conditions must be met.” These included a balanced budget, reasserting Fed independence, and even — least likely — international consensus. A gold standard, Barron’s averred, is “not a game of solitaire.” The editorial poured cold water on restoring the gold standard, on the grounds that economic stability took precedence over establishing sound money.

The next day, the editors of the Wall Street Journal chimed in with their own editorial decrying the equivocation in the GOP’s gold standard plank. It was “pretty good — but only pretty good,” the editors noted, objecting to the idea that a return to the gold standard “must await the restoration of both a sound domestic economy and a stable world economy.” The Journal asked: “When, if ever, will all the world have a stable economy?”

The savvy of that question from the summer of 1952 would appear to animate the Journal’s editorial today lamenting that Mr. Milei’s “free-market ideas will fail” absent monetary reform. After all, he “is pushing a big-bang economic reform to make the once-rich nation prosperous again.” Yet “the drama now unfolding” in Argentina, the Journal notes, centers on “whether his reforms can take hold before the public loses confidence in his efforts.”

Inflation in Argentina is raging at some 200 percent, the Journal reckons — “the fruits of left-wing populist governments in the Peron tradition” — and “the value of the peso has collapsed.” So the essential first step for Mr. Milei, as the Journal sees it, would be to restore confidence in the peso — or to embrace his campaign pledge of dollarization. “A stable currency that people trust is essential,” the Journal avers, “and his reforms will fail without it.”

Which brings us back to 1952, when America had a chance, in the election of Eisenhower, to restore a dollar defined as a weight of gold and exchangeable for it on demand. In the end, the Barrons’ argument prevailed, and monetary reform got put off. Bretton Woods held for a while. Yet 1952 and all that is a cautionary tale. For decades Argentina ignored its currency while trying to fix its economy. There could be no bigger bang than going for the gold.