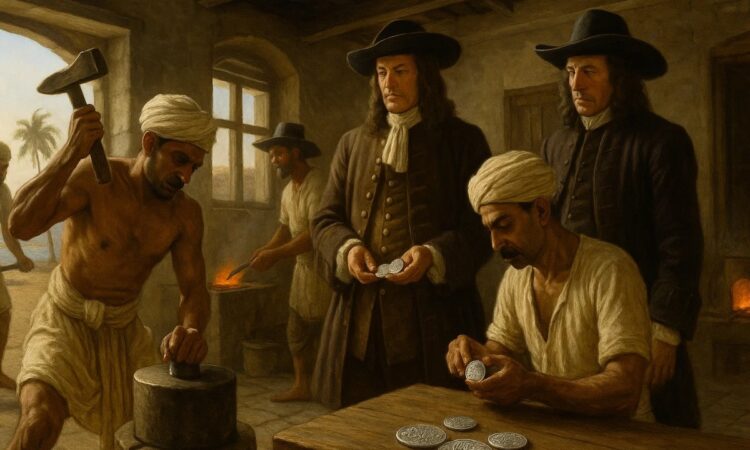

The East India Company, which ruled for almost 200 years, began producing silver and copper coins in Bombay in the year 1677 on October 15. It was authorised so by King Charles II of England and was the first time the trade company ever branched into producing coins in India.

The decree declared Bombay the first in India where a private trade corporation was licenced to print its own currency. Prior to that, only monarchs and empires were capable of striking coins.

The Company’s coins were Indian in appearance and in accordance with local conventions, but their sanction was in London.

It was a pragmatic move designed to facilitate trade, but it also began a new form of domination, economic strength supplemented with political sanctions.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE RUPPEE

The word rupee comes from the Sanskrit term rupiya, which was the term used for the silver coin.

It reached the modern-standard form in the 1540s with Sher Shah Suri.

The rupee contained roughly 11.5 grams in silver and gained fame due to its standardized purity.

The Mughals maintained that system and promoted it all over the kingdom.

During the third Mughal emperor, Akbar’s reign, the monetary denomination used in trade from Kabul till Bengal was the rupee.

The coin also bore the title of the emperor in Persian writing. The fineness and mass in silver made the coin trustworthy. The people accepted it since its value was guaranteed and not from the issuer.

Paisa, a copper coin, was utilised in day-to-day exchange. Sixty-four paisas comprised a single rupee. The two comprised a working system which connected the traders, the rulers, and the markets.

“Sher Shah established a new silver currency, the rupiya, weighing 178 grains. Its stability gave India a uniform standard of exchange for the first time in centuries,” penned Nilson Wright, a civil servant during the British Raj in his work The Coinage and Metrology of the Mughal Emperors.

HOW THE EAST INDIA COMPANY ENTERED THE PICTURE

When the EIC arrived, it was a trading faction with commerce stations, and not with political powers.

The ships brought bullion from Europe in order to buy Indian goods like cloth and pepper.

Transportation of heavy silver over large distances was risky and costly. Minting at the local level offered a pragmatic solution – produce coins which the local merchants were used to identifying.

The chance came when Bombay was ceded to England in 1661 as a result of the wedding alliance of Charles II and Catherine of Braganza.

The Company then secured a mandate from the king to govern the island, in effect conveying the right to strike coinage.

The Company was officially sanctioned with royal permission to strike coins in Bombay by the year 1677.

Even smaller payments were also made in copper coins. They were stamped with plain marks or flower pattern and dates in the Islamic calendar.

Expansion During Presidencies Bombay’s example was soon followed elsewhere. Madras opened a mint in 1692, and Calcutta began minting coins early in the 18th century. Each presidency produced coins suited to its region. Some differed slightly in weight or fineness.

Such differences were noticed by traders. A coin which was less pure or lighter was marked down instantly in the market.

The Company endeavoured multiple times at coordinating the standards among the presidencies but only managed in part. India’s markets retained a combination of Mughal, local, and Company concerns well into the 19th century.

1835: ONE COIN FOR ALL

The commerce and government in the 1830s called for uniformity. In the year 1835, the East India Company consented to a single coinage in its territories.

The silver rupee was the customary coinage. It carried the title and the name of the British monarch in English and Persian.

This reformed simplified trade and account keeping. It also affirmed that monetary authority had shifted from the Indian kingdoms to the government of the Company.

Following the Revolt of 1857, the administration in India was transferred from the East India Company to the British Crown. The coinage also was transferred.

The Crown coinage replaced the head of Queen Victoria, styled Empress of India, for the Company’s arms. The rupee, however, underwent little change. The people continued to use rupees and paisas. The weight, the metal, and the divsions were the same.

Through later reigns, Edward VII, George V, and George VI, the rupee remained the standard coin of daily life. Even with design changes, the idea of the rupee as India’s unit of value continued unbroken from the 16th century to the 20th.

The coinage process encompassed the establishment of value. It provided a means for the Company’s price control, wages, and trade in its domains.

Financial control also benefited its eventual expansion into government and tax. The transformation from trader to king began with a coin die, and not with cannon.

The initial Bombay Mint coins carried the semblance of India but carried foreign authority.

It was a pilot project in the broader scheme in which India’s currency – and later its politics – came under foreign jurisdiction.

That early rupee of Sher Shah Suri took a very long route: from Mughal courts, via the Company’s coinage, to the British Crown’s empire. Its imprint in each state it touched was left in the coinage met

– Ends