Status of the US Dollar as Global Reserve Currency: Share Drops to Lowest since 1995. Central Banks Diversify to “Nontraditional” Currencies and Gold

But China’s renminbi keeps losing ground.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

The US dollar, still the #1 reserve currency held by central banks, keeps losing share in bits and pieces ever so slowly against a mix of other reserve currencies as central banks diversify their holdings of dollar-denominated assets to assets denominated in other currencies. And they’re also adding to their holdings of gold.

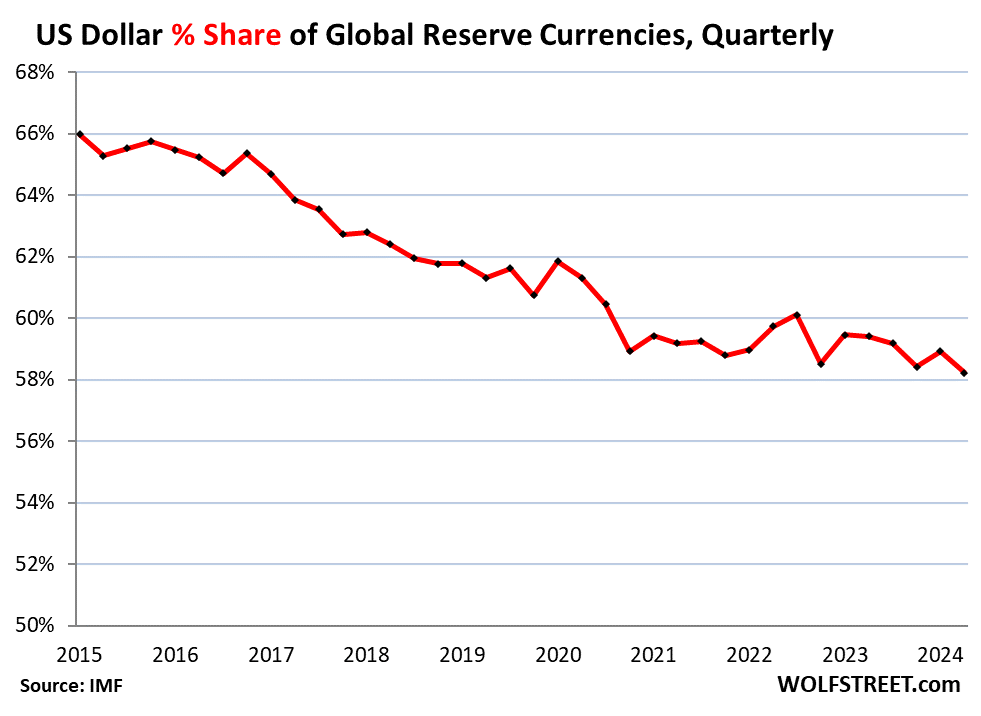

The share of USD-denominated foreign exchange reserves – assets that central banks other than the Fed hold that are denominated in USD – ticked down to 58.2% of total exchange reserves in Q2, the lowest share since 1995, according to the IMF’s new COFER data.

Over the past 10 years, the dollar’s share has dropped by about 8 percentage points, from 66% in 2015 to 58.2% in 2024 so far. If this pace continues, the dollar’s share will kiss 50% in 10 years.

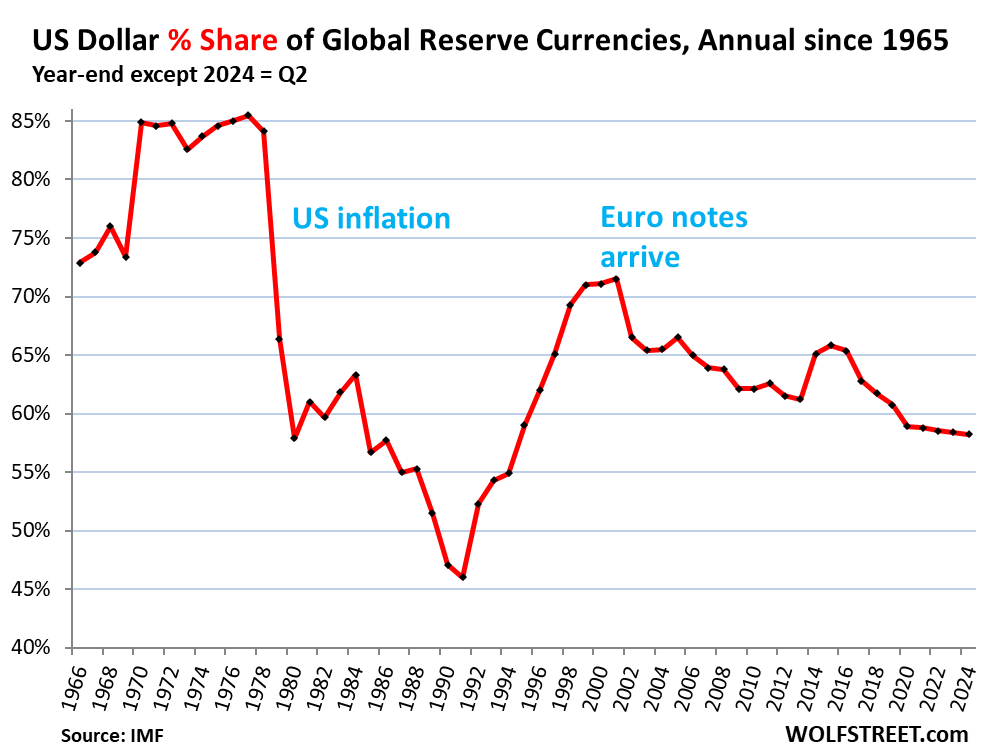

The long view back to the 1960s shows that the USD’s share of global reserve currencies was a lot lower in the 1970s and 1980s. The share collapsed from 85% in 1977 to 46% in 1991, as inflation had exploded in the US in the 1970s and into the 1980s, and the world lost confidence in the Fed’s willingness to get this inflation under control.

By the 1990s, with inflation on decline for a decade, confidence returned, and central banks loaded up on dollar-denominated assets again, until the euro came along, which combined the major European reserve currencies into one, making it a solid alternative to the dollar.

The chart shows the share of the USD at year end except in 2024, for which we use the Q2 figure.

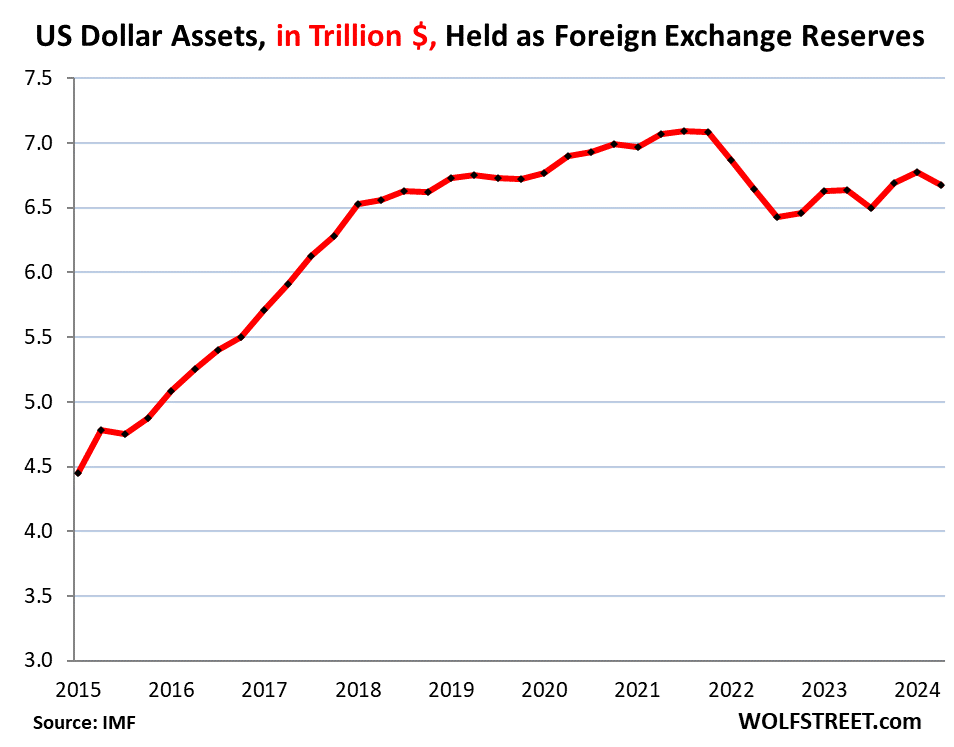

In dollar terms, central banks held foreign exchange reserves in all currencies of $12.35 trillion in Q2. Of this amount, holdings of USD-denominated assets dipped to $6.68 trillion.

These US-dollar denominated assets include US Treasury securities, US agency securities, US government-backed MBS, US corporate bonds, even US stocks, held by central banks other than the Fed.

Excluded are assets denominated in a central bank’s local currency, such as the Fed’s holdings of Treasury securities, and the ECB’s holdings of euro-denominated assets.

Central banks have not been “dumping” their dollar-assets – in dollar amounts, their dollar-holdings haven’t changed much and are not far off the peak in 2021. But as overall foreign exchange reserves grow, they’re taking on assets denominated in many alternative currencies, and the dollar’s share of the total declines.

The other major reserve currencies.

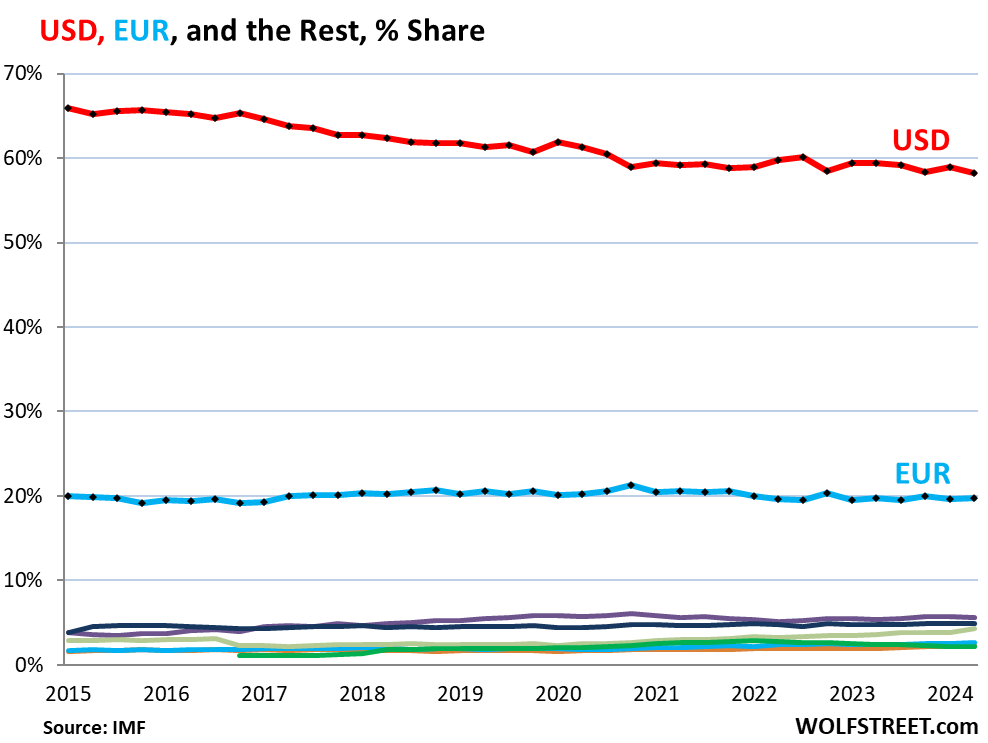

The euro is the perennial #2, with a share that has for years been stuck at around 20%. In Q2, the share was 19.8% (blue line in the chart below).

The major alternatives to the USD and the EUR, the “nontraditional reserve currencies,” as the IMF calls them, are the colorful tangle at the bottom of the chart.

The rise of the “nontraditional reserve currencies.”

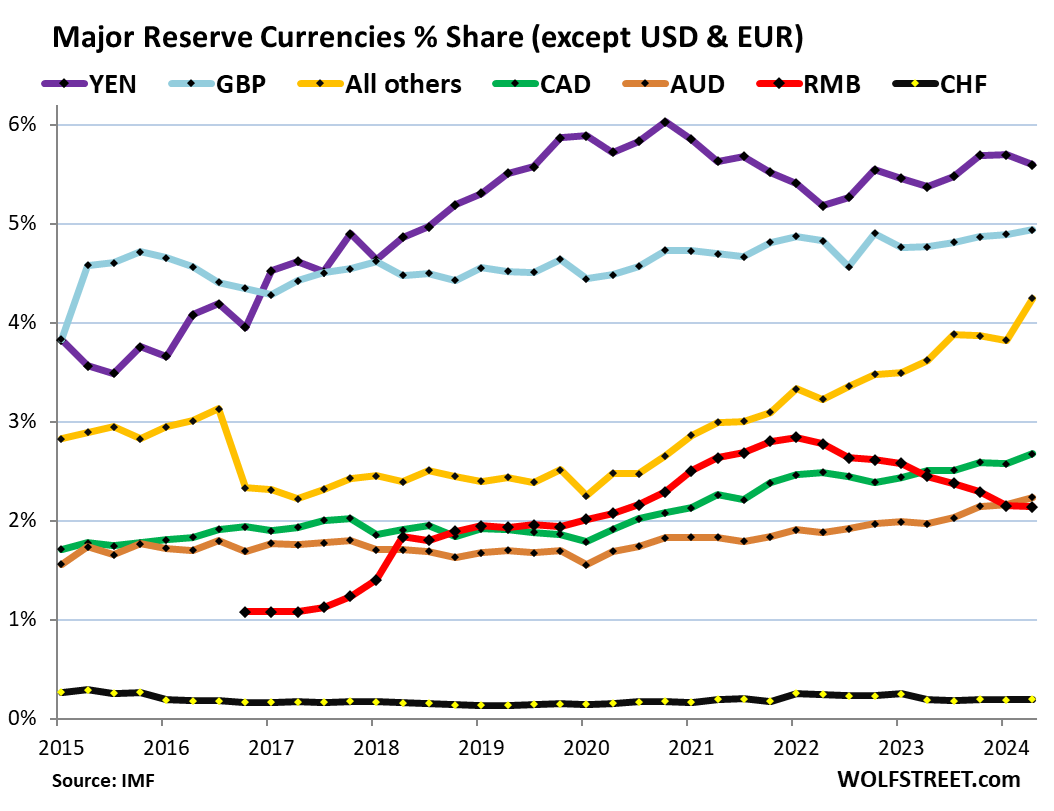

Here we hold a magnifying glass over the colorful tangle in the chart above. And what we see is that these other currencies, except for the Chinese RMB, have been gaining share since 2015, while the dollar has been losing share and the euro has been hanging on to its share.

So it’s not one currency that’s gaining against the dollar; it’s that a lot of “nontraditional reserve currencies” are gaining share.

“All others” (yellow in the chart below) are a large group of currencies, whose combined share has soared to 4.2% in Q2, from 2.5% at the end of 2019, the biggest gainer, composed of currencies that are not listed separately in the IMF’s data. The RMB used to be part of this group until 2016.

The diversifiers. The IMF said in a 2022 paper that there were 46 “active diversifiers”: central banks in advanced economies and emerging markets, including most of the G20 economies, that have at least 5% of their foreign exchange reserves in “nontraditional reserve currencies.”

The Chinese RMB (red) is the exception. When the IMF added the RMB to its basket of currencies backing the Special Drawing Rights (SDR) in 2016, the currency was seen as the coming threat to the dominance of the USD as global reserve currency. China is the second largest economy in the world, and it makes sense that it would have a major reserve currency.

But that has turned out to be not the case. The RMB is handicapped by capital controls and convertibility issues. Central banks appear to be leery of holding RMB-denominated assets. And it plays only a small and declining role as a reserve currency. Even the Australian dollar (brown) now has a larger share than the RMB.

Percentage share of major foreign exchange reserves in Q2 that the IMF’s data lists separately:

- Japanese yen, 5.6% (purple), third largest reserve currency behind USD and EUR, despite the plunge of the yen’s exchange rate against other major currencies.

- British pound, 4.9% (blue), fourth largest reserve currency.

- “All other currencies” combined, 4.2% (yellow).

- Canadian dollar, 2.7% (green).

- Australian dollar, 2.2% (brown).

- Chinese renminbi, 2.1% (red).

- Swiss franc, 0.2% (purple).

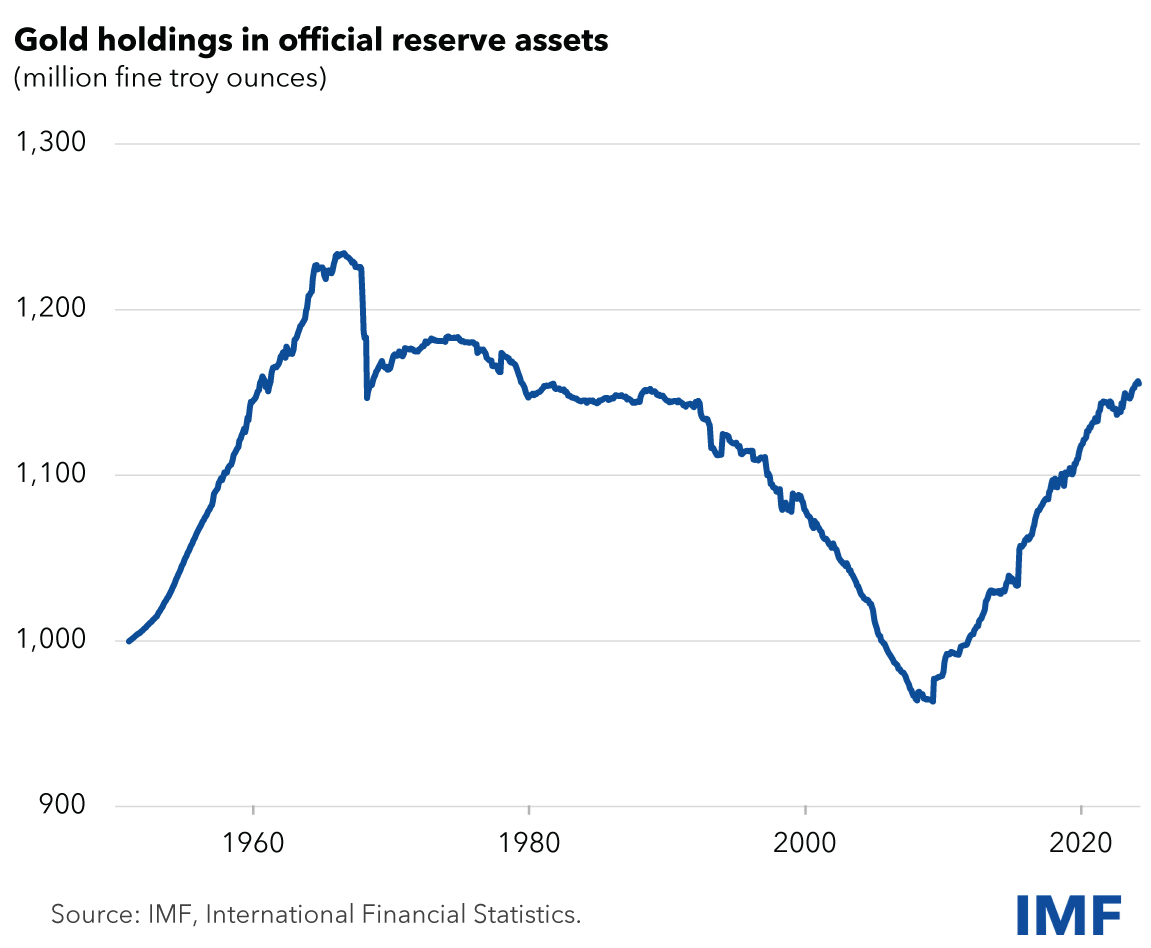

Gold has re-emerged as a favored central bank reserve asset.

Gold bullion is not a “foreign exchange reserve” – the data above. It’s a central bank “reserve asset.” So it doesn’t really fit into this discussion of foreign exchange reserves. But it can replace foreign exchange reserves, such as Treasury securities, on a central bank balance sheet. And it has been doing that.

Central banks spent 50 years unloading their gold holdings. But over the past decade, they’ve been rebuilding their gold holdings.

They’re currently holding 1.16 billion troy ounces, roughly back to where it had been in the 1970s, according to the IMF. At today’s price, that’s $3.1 trillion in gold, compared to $12.35 trillion in foreign exchange reserves (chart via the IMF):

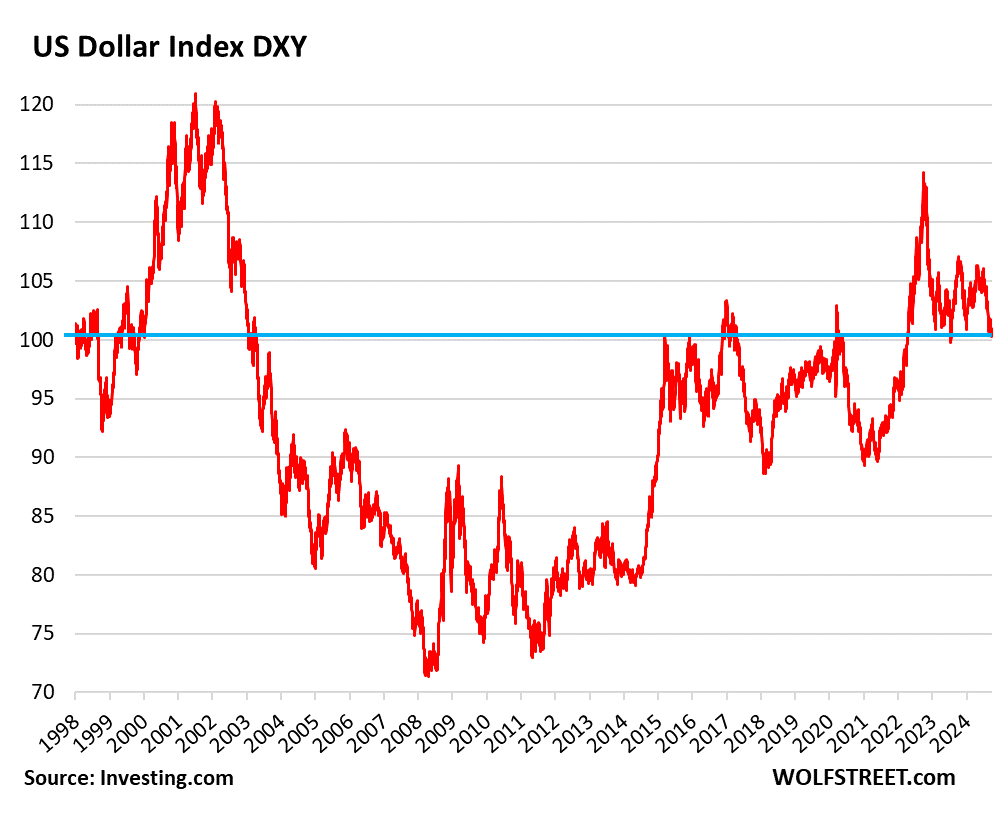

USD-exchange rates impact foreign exchange reserves.

Foreign exchange reserves are all reported in USD. Holdings in currencies other than USD are translated into USD at the exchange rate at the time. So the exchange rates between the USD and other reserve currencies change the magnitude of the non-USD assets – but not of the USD-assets.

Japan’s holdings of USD-denominated assets are expressed in USD, and they don’t change with the YEN-USD exchange rate. But Japan’s holdings of EUR-denominated assets are translated into USD at the EUR-USD exchange rate at the time. So the magnitude of Japan’s holdings of EUR-assets, expressed in USD, fluctuates with the EUR-USD exchange rate, even if Japan’s holdings don’t change.

Despite major turmoil in exchange rates, over the long run, the Dollar Index [DXY] hasn’t moved much. The DXY tracks the USD exchange rates against a basket of six currencies (EUR, YEN, GBP, CAD, Swedish krona, and Swiss franc). And the DXY, currently at 100.4, is back where it had been in 1998:

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()