This article was originally published in Vol. 4 No. 3 of our print edition.

In August 2023, the BRICS countries held their fifteenth summit in Johannesburg, which was attended by its founders: Brazil, Russia, India, and China. The summit concluded with the South African president’s announcement, which included BRICS’s expansion plans, inviting Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates to join the bloc. As of January 2024, the bloc has indeed expanded, and now also includes Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Furthermore, a total of fifteen countries have also applied to join BRICS. These include major stakeholders in the energy sector, such as Kazakhstan, Nigeria, Kuwait, and Venezuela.

In October 2024, Russia will become (Editor’s update: the event is currently taking place) the next host of the enlarged BRICS+ annual summit as the country chairs the bloc. Russian President Vladimir Putin announced that the summit (and Russia’s presidency) would be dedicated to establishing a ‘fair world order…enhancing the role of BRICS states in the international monetary and financial system [and] developing interbank cooperation, providing assistance in transforming the international payment system, and expanding the use of the national currencies of BRICS states in mutual trade’.1 This without further context suggests that additional expansion, de-dollarization, and opportunities to offset US hegemony could be on the agenda.

These fears are further fueled as Washington and Brussels become ever more hostile to many BRICS countries through their use of economic sanctions on countries like Russia, China, and Iran. Although it has become clear by now that Brussels’ actions taken against Russia (and in some cases China) were not able to bring them to heel, preventing them from conducting cross-border trade in the world’s reserve currency is in fact causing uncomfortable situations for the affected countries. As BRICS expands its members with rapidly emerging markets (EM) while the West’s willingness to use economic sanctions and the leverage it has from holding the global reserve currency increases, the bloc could shift away from the usage of the greenback in international trade to reduce its vulnerability to the West and its financial institutions.2

After establishing the possible underlying assumption for the shift, it is important to explain the ‘how’. This will be done by showcasing the expanded competitiveness of the BRICS, their strengths against the current status quo—established and maintained by the G7—and how it could capitalize on these to protect itself from the growing hostility through challenging the US dollar’s role in global trade. Moreover, we aim to present the most likely challenger to the US dollar and highlight its ‘dethroning capabilities’. The main objective of the essay is to find out whether the US dollar is likely to follow in the footsteps of the nineteenth-century British pound, or whether it can hold on to its hegemony as the most important currency in the world.

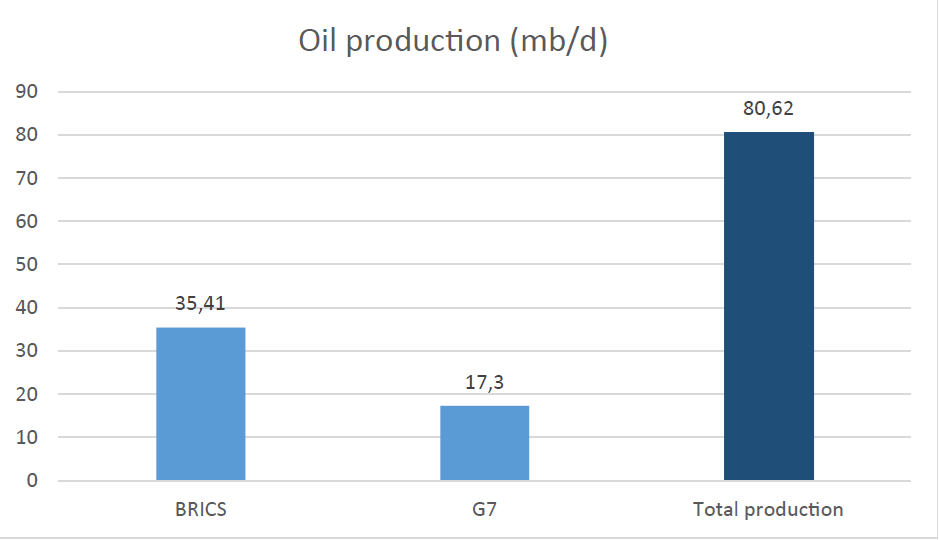

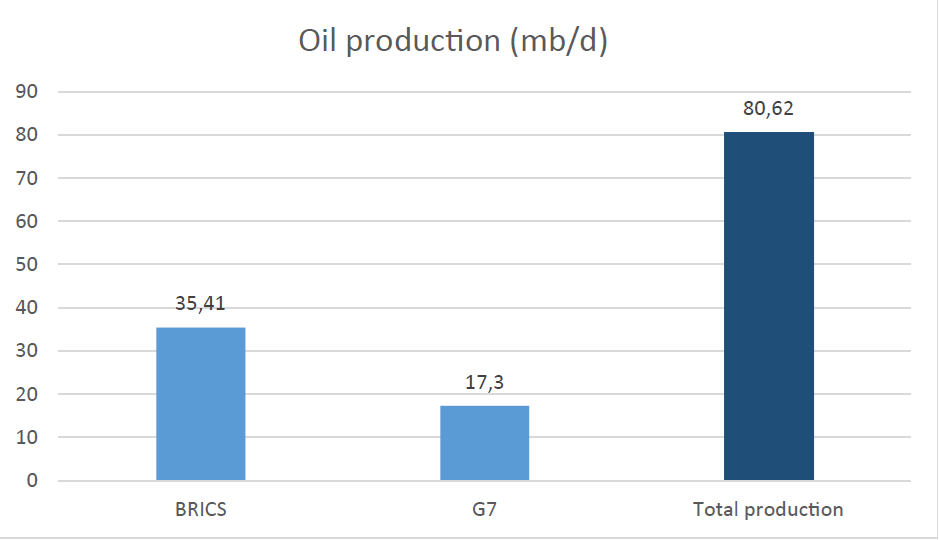

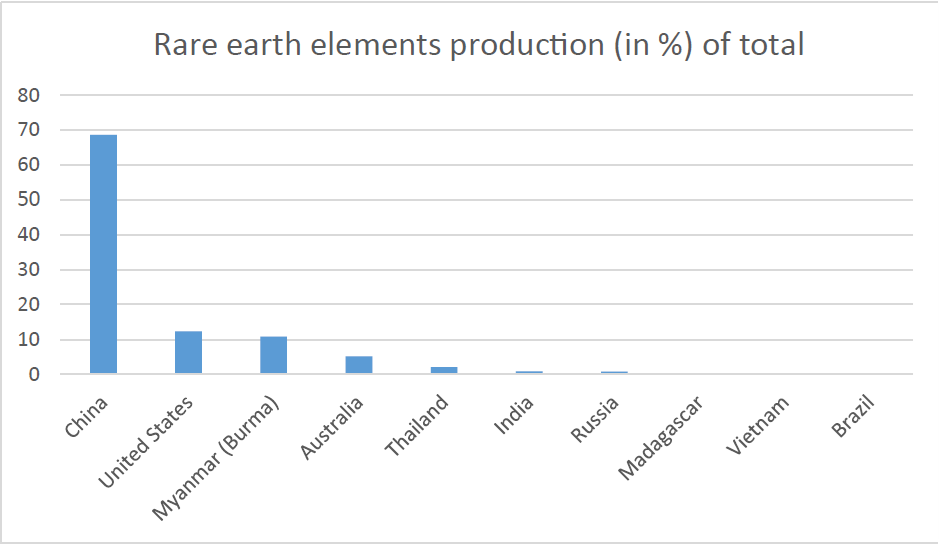

As has been outlined earlier and widely discussed in geopolitical discourse by such prominent scholars as Cochrane and Zaidan,3 BRICS+ has enormous leverage on the rest of the world. In addition to its demographic significance, it occupies critical roles in defining current and future markets such as the oil and gas industries and the rare earth elements (REE) sector. As was highlighted by a US Energy Information Administration report,4 BRICS countries (before the 2024 expansion) were responsible for almost 20 per cent of global oil production, rising close to a staggering 40 per cent after the bloc’s expansion (see Figure 1).

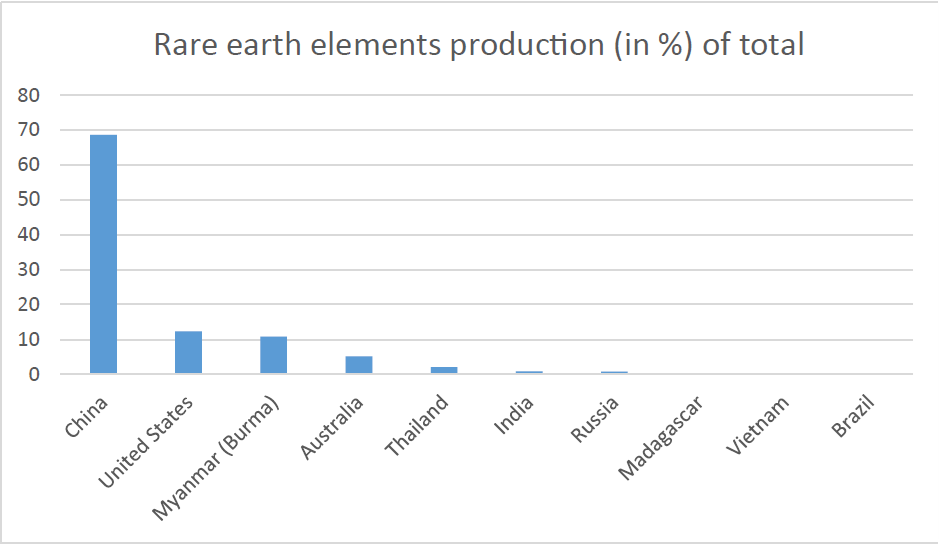

In terms of natural gas, the biggest producer is the USA, but the next top three competitors are all BRICS countries (Russia, Iran, and China). In fact, out of the top ten gas producers in the world, five are BRICS countries.6 Furthermore, China, a founding member of the bloc, produces almost 70 per cent of the world’s REE, greatly surpassing the second largest producer (US) with its 13.33-per-cent production rate (Figure 2). Along with China, India, Brazil, and Russia are also members of the REE production ‘top ten club’ while G7 countries lag behind, with only the US coming in second behind China.

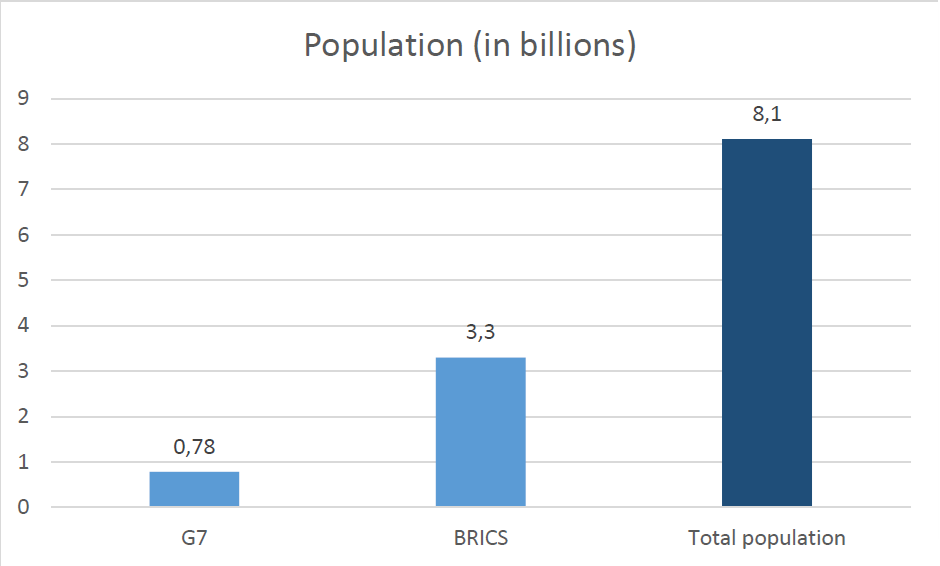

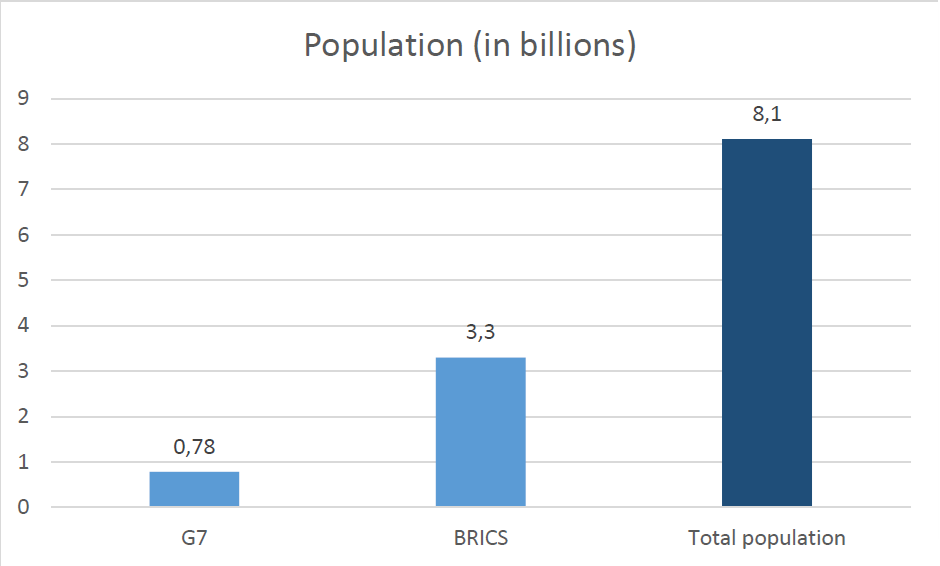

Taking geography and demography into consideration, BRICS countries also stand out. In 2023, the bloc’s population, which includes citizens of the two most populous countries in the world (India and China), surpassed 3.3 billion people (Figure 3).

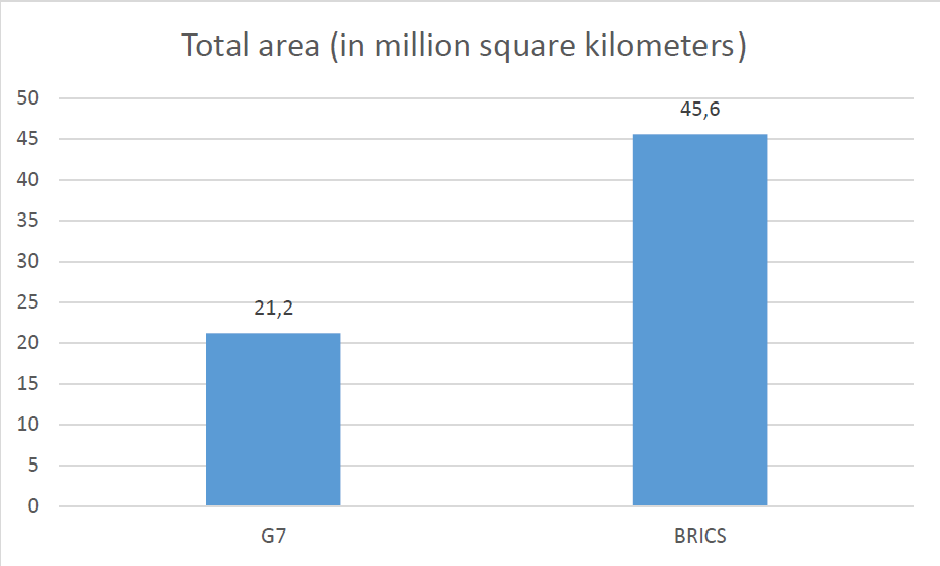

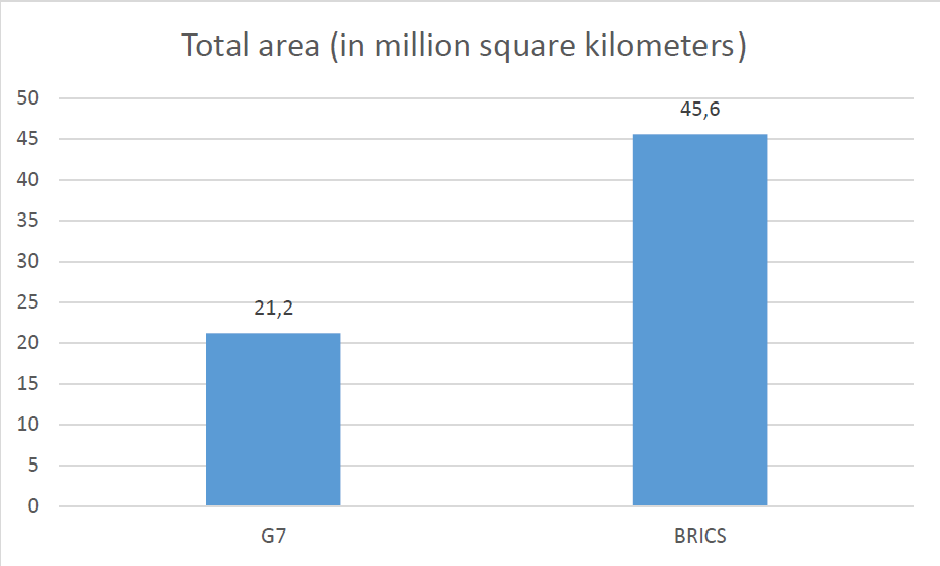

Moreover, the intergovernmental organization’s founders belong to the seven largest countries in terms of area, and are the world’s largest economies, along with the G7 countries and South Korea (Figure 4).

In addition to successfully capitalizing on its endowments and resources, the bloc follows an exceptionally conscious trade policy which builds upon connectivity throughout member states and EM in the region. According to an ING study,10 BRICS countries’ imports from within the bloc and regional developing countries accounted for more than half of their total imports in 2022 (54 per cent). Comparing ING’s 2022 data with values from 2015,11 it can be observed that BRICS imports from the eurozone, the US, and other developed countries have decreased by a total of 4 per cent, while imports from other BRICS countries and EM increased by 5 per cent. Taking into account the BRICS policy of expansion and self-reliance, this 9-per-cent shift in import preferences could further increase in the future, especially with the organization’s newest additions like the heavily sanctioned Iran.

Subtle, discernible trends are also beginning to emerge regarding their export activities, warranting cautious conclusions. Exports within BRICS countries decreased by 3 per cent and were rerouted to the eurozone and EM in the region. These intentions are both economically and politically viable as they drive a new chain of dependencies in the region between supplier (BRICS) and recipient (EM) countries.12 Moreover, at the global level, BRICS could also hold sway over international trade through its influence on the Suez Canal (with Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Ethiopia joining the alliance) which accounts for between 12 and 15 per cent of global trade.13 It is important to note, however, that the regional advancement and economic ambitions of BRICS primarily manifest in the arena of fuel trade, owing to the member states’ vast reserves of raw materials and extraction capacities.

In light of the above, it can be confidently stated that BRICS (by upholding its expansion intentions and successfully channelling EM in the region) could be a viable counterpart to its rivals. These statistics and economic achievements led us to consider and examine BRICS’ chances of dethroning the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency, thus establishing a new status quo and hegemony. The examination will be carried out in the following section by highlighting the significance of the only potential challenger to the USD, the renminbi, with its strengths and weaknesses, along with the drivers motivating the idea of a unifying, shared currency within the bloc. The topic of a BRICS-issued common currency—‘BRICS Pay’—has been on the agenda for the bloc for many years now,14 but as member countries’ national economies vary widely both in terms of structure and performance, along with the fact that they were not able to conduct sufficient amounts of trade with each other, the idea of a new currency (within the bloc) which could challenge the USD as the global reserve currency has never really been taken seriously. However, given the current and foreseeable economic and political climate between BRICS and the West, the assumption of an already existing, shared currency is worth revisiting for many reasons.

Firstly, as it has already been outlined, BRICS entered an era of expansion in 2024. Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates were accepted as members of the organization, while some fifteen other states’ applications are still pending. Furthermore, the bloc continued to assert its influence, as showcased by its defining trade activity, while the incoming Russian presidency gives rise to further uncertainties. Secondly, due to the rapidly changing geopolitical landscape following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China’s continuing economic development and rapidly growing influence over critical industries across the globe, and Iran’s accession to the alliance, the economic and political hostility of Washington and Brussels towards BRICS is increasing. Sanctions, anti-subsidy investigations, and trade barriers are being introduced and set up to maximize political and economic leverage. Thirdly, as the IMF’s Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) survey points out,15 the share of the American dollar held by central banks has also been on the decline, with a long-time record low in recent years.

Thus, the greenback’s systematically growing trend was brought to a halt in recent years (though future market trends cannot yet be accurately predicted). Finally, concerns erupted as the World Gold Council (WGC) published its latest data for 2023, which showed major BRICS countries stockpiling gold worth billions of dollars, making them the largest buyers of the precious metal in the last year.16 China alone secured 225 tonnes, which is the country’s largest purchase since the 1970s. What is more, according to the WGC, the BRICS gold accumulating frenzy will continue, as the member countries’ central banks continued to buy gold in early 2024. These tendencies could lend credibility to speculations on the introduction of a BRICS common currency backed by gold.

However, despite all the above, BRICS economic empowerment is still insufficient to create an entirely new currency accepted and used worldwide. We believe that there are two possible options for the bloc’s members to distance themselves from the dollar: one short-term and one long-term solution. The quicker and more feasible option entails encouraging the simultaneous use of already established currencies within BRICS countries, as Russia has been doing with China (80 per cent of trade between Russia and China is conducted in rouble or yuan) or with India. It must be noted, however, that the more trade one country conducts with another, the more reserves of each other’s currencies they must hold, which they should be able to quickly and easily convert into their own currency at any time. This raises the problem of convertibility, which poses challenges in countries like India, where the state prohibits citizens from taking large amounts of cash out of the country through its capital control procedures. Furthermore, should rupees be taken out of India, they must still be converted into another currency (most commonly USD) prior to being exchanged for the currency of preference. Thus, the use of BRICS currencies cannot at present challenge the US dollar’s hegemony on the international stage. The long-term approach for BRICS is to introduce an already accepted and successful currency as their reserve, which carries at least potential credibility on the international stage outside of BRICS as well. As of today, the only currency which could possibly fill this role is the Chinese yuan. Backing trade with the yuan, however, would require member states to align their monetary policy and many aspects of their fiscal policy with China. Although for now this does not seem like a deal-breaker, it could fuel disputes between BRICS countries further down the road.

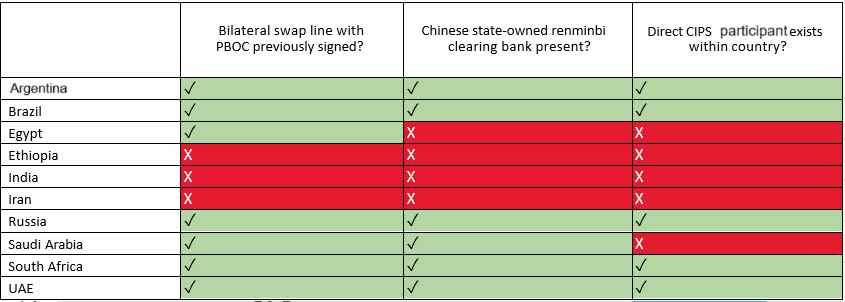

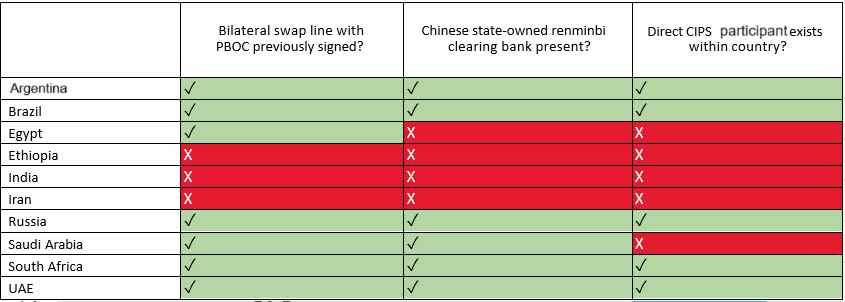

Taking a closer look at China’s economic aspirations, it can be observed that preparations have already started for a potential shift to de-dollarization (and sanction de-risking). Similarly to Russia or India, China, the largest and strongest economy in the bloc, has also developed its own yuan-based payment system, the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), which serves as an alternative to the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT). CIPS has demonstrated a pattern of steady expansion (see Figure 5) since its introduction in 2015, boasting a current roster of close to 100 direct participants and an extensive network comprising over a thousand indirect participants spanning the globe.17

Along with CIPS’s growing global influence, China’s regional dominance through trade also deserves attention. As was highlighted earlier, BRICS countries are increasingly focused on fostering trade within the bloc, as they are more likely to gain economic and political leverage in EM and developing economies, where they can also occupy critical positions in the foreign exchange market by trading in their national currencies and regulating their exchange rates. This allows them to limit the expansion potential of the US dollar and somewhat counterbalance its global strength.

Brazil, a founding member of BRICS, serves as a perfect example of the expanding influence of the renminbi. Although Brazil’s foreign exchange reserves remain dominated by the dollar (which accounted for more than 80 per cent of their total reserves in 2022 according to the country’s central bank),18 the share of renminbi has been on the rise lately. By 2022, Brazil—having had no yuan reserves previously—had accumulated reserves amounting to more than 5 per cent of its total FX reserves, surpassing the euro’s 4.74-per-cent share. Furthermore, in 2023, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the central bank of the People’s Republic of China, granted approval to Brazil’s first financial institution accepting the yuan, commencing cross-border yuan settlements shortly thereafter. Also in 2023, Brazil welcomed its sole direct participant in CIPS, an entity controlled by a Chinese state-owned bank.19

‘BRICS cannot currently present a clear alternative to the present hegemon’

The Russian economy and its financial institutions have also undergone rapid convergence with China in recent years, especially in light of the war in Ukraine. There has been a discernible trend in recent years whereby Russian enterprises are increasingly availing themselves of yuan-denominated debt financing. Furthermore, it has been observed that between January 2022 and March 2023, the exposure of Chinese banks to Russian counterparts surged nearly fourfold within a span of just over a year.20 As of 2023, more than thirty banks in Russia have joined CIPS as indirect participants. Moreover, the mounting pressure from influential Russian industry groups is increasingly compelling those banks in Russia that have not yet joined to do so. In addition, the Russian minister of finance declared that during the first three quarters of 2023, 70 per cent of Sino-Russian trade transactions were conducted in yuan.21 Moreover, in the year of the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, 2022, invoicing of Russian exports in yuan surged from nearly zero to 16 per cent.22 While the majority of associated payments involved Chinese entities, certain commercial transactions occurred between Russian organizations and counterparts in India, Japan, or Southeast Asia, also denominated in yuan. Thus, like the dollar, the yuan served as a facilitator of transactions between entities of two countries where the yuan is not the local currency.

Saudi Arabia, which exports more than 25 per cent of its oil to China, has also come to an agreement in a long-discussed matter that would facilitate oil payments in yuan for energy suppliers. The agreement includes the establishment of bilateral swap lines between the two countries. Similarly, the United Arab Emirates has also started to make payments in dirham and yuan in the oil and gas sectors as the country prepares to launch the mBridge Project.23

Iran is another country in which China is successfully expanding the use of its currency. Due to international sanctions, Iran has reportedly been using yuan to conduct trade with China since 2012.24 Since the invasion of Ukraine, Russia has surpassed Iran as the most sanctioned country, and as such has also started weighing the use of renminbi to facilitate trade with Iran. Recent initiatives aimed at increasing the use of the yuan in South Africa and Egypt have been relatively modest compared to other BRICS countries; however, a growing trend is also evident within these nations.25

Nevertheless, despite BRICS countries’ impressive recent expansion and acquired regional and international leverage both economically and politically, the US dollar’s position as the global reserve currency seems unshakable at present. This can be explained from both a regional and an international perspective. According to statistics from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), regionally—despite progress by BRICS and the renminbi—the vast majority of foreign exchange transactions in the region included the use of the US dollar. Broken down to some BRICS countries’ currencies, the numbers are telling; rupee, real, yuan, and rand transactions were reliant on the dollar at rates of 97 per cent, 95 per cent, 94 per cent, and 88 per cent respectively.27 Upon examining the situation globally, it can be observed that 90 per cent of all foreign exchange transactions in the world were conducted with the help of the US dollar.28

What is more, despite the member states’ rapid achievements with regard to expanding regional trade dominance through increased volumes of exports and bilateral trade agreements in terms of regional imports, their exposure to the dollar remains high. Even though only 18 per cent of Chinese exports went to the US,29 47 per cent of China’s cross-border payments were conducted in dollars in 2023. This tendency tends to be similar in other BRICS countries as well: exports are disproportionately invoiced in dollars (compared to the share of exports to the US).30 This even holds true for the heavily sanctioned Russia, which despite Western blowback for invading Ukraine continued to settle a third of its exports in dollars in 2022.31 This shows that the US dollar is still the most reliable and preferred currency, even for trade deals between states outside the US.

From a non-regional international perspective, the dollar’s position is steadfast. One of the most significant reasons for the decline in the prominence of the pound sterling during the interwar period was the surge in international US-dollar-denominated debt issuance,32 which allowed the dollar to overtake the pound in the race for the global reserve currency title. Since then, according to ING’s prominent study,33 the US dollar managed to not only keep its title but to further strengthen it, as securities representing credit relationships over the past decade have seen a consistent annual increase in the valuation of American equities.

Moreover, the Sino-Indian conflict further bolsters the US dollar’s position on the international stage by narrowing opportunities for consensus between the two most influential countries within BRICS. The border disputes, violent skirmishes, and economic sanctions banning certain Chinese exports to India hinder the alliance from uniting to back a common currency to counterbalance the US dollar. Additionally, it is important to note that the most significant shift in the global strength of the dollar will most likely occur when oil and gas prices are no longer denominated in US dollars, which favours giant producers and exporters like most BRICS countries and disadvantages net importers of these products.

In conclusion, due to the dollar’s embeddedness in global financial institutions and its role in international trade between countries beyond the US and its sphere of influence, it will likely remain the global reserve currency for many reasons. Firstly, although regional preferences are shifting, and the growing potential demand for alternatives to the US dollar is increasing, BRICS cannot currently present a clear alternative to the present hegemon, since the vast majority of foreign exchange transactions (even in BRICS countries) use the dollar. Moreover, most international trade is conducted in dollars, even between states where the dollar is not the national, state-issued currency. Secondly, in terms of the processes of de-dollarizing financial assets, the private sector is less active and not as heavily invested in it as (BRICS countries’) central banks. Although the dollar’s share in central banks’ currency reserves has decreased, the use of the American currency remains exceptionally high in trade, debt issuance, and generally in the global currency market. Thirdly, the increasing use of alternative currencies does not threaten the dollar at present; rather, it enhances competition among regional currencies due to the fragmentation of trade and capital flows: the de-dollarization of the system would probably lead to a more diverse market, rather than a direct increase in the role of one national currency. Lastly, another factor hindering the BRICS de-dollarization processes is the lack of synchronization among regional trade, capital flows, and currency markets. A further barrier is the political conflict between some BRICS countries, like the above-mentioned Sino-Indian border conflict, or minor ones like the dispute over the legal status of the Caspian Sea with regard to its resource distribution in the case of Russia and Iran.

As can be observed from the 2023 de-dollarization summary of ING’s comprehensive study,34 the US dollar dominates the FX and financial markets, with an almost 50-per-cent share in most aspects, whereas major currencies like the yuan, the euro, or the yen represent only a fraction of the dollar’s share. However, its overall significance, compared to data from 2015, has decreased. The currency’s share of total SWIFT payments and cross-border liabilities, along with its non-financial-sector foreign assets and reserves in central banks outside the US all decreased over the examined period. This could potentially serve as a warning sign for the US dollar, as BRICS countries’ de-dollarization efforts further intensify in both politically and economically salient countries around the world.

All things considered, the West must pay close attention to the incoming Russian presidency of BRICS, as in times of decoupling and the building of opposing blocs. In addition to the hyperrealist approach to political economy and international trade, tables can easily be turned in the long run if BRICS manages to successfully capitalize on its expansionist intentions and growing influence around the globe. In light of the US dollar’s overall decline as a share of global FX reserves, the threatening international expansion of CIPS, and the BRICS countries’ overwhelming abundance of natural resources paired with the West’s hostile sanctions and anti-subsidy investigations, reasons for caution and concern are evident.

NOTES

1 ’Priorities of the Russian Federation’s BRICS Chairmanship in 2024’, BRICS Russia 2024, https://brics-russia2024.ru/en/russia-and-brics/priorities/, accessed 2 June 2024.

2 Robert Greene, ‘The Difficult Realities of the BRICS’ Dedollarization Efforts—and the Renminbi’s Role’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (December 2023), https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/12/05/difficult-realities-of-brics-dedollarization-efforts-and-renminbi-s-role-pub-91173, accessed 3 June 2024.

3 Logan Cochranem and Esmat Zaidan, ‘Shifting Global Dynamics: An Empirical Analysis of BRICS+ Expansion and Its Economic, Trade, and Military Implications in the Context of the G7’, Cogent Social Sciences, 1/10 (December 2024), https://idp.ed.ac.uk/idp/profile/SAML2/POST/SSO?execution=e1s1&_eventId_proceed=1.

4 U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), ‘Petroleum and Other Liquids’, www.eia.gov/international/data/world/petroleum-and-other-liquids/annual-refined-petroleum-products-consumption, accessed 18 February 2024.

5 U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), ‘Petroleum and Other Liquids’.

6 ‘Natural Gas Production by Country’, Worldometer (2024), www.worldometers.info/gas/gas-production-by-country/, accessed 3 June 2024.

7 ‘Distribution of Rare Earths Production Worldwide as of 2023, by Country’, Statista, www.statista.com/statistics/270277/mining-of-rare-earths-by-country/, accessed 19 February 2024.

8 ‘Total Population of the BRICS Countries from 2000 to 2028’, Statista, www.statista.com/statistics/254205/total-population-of-the-bric-countries/, accessed 23 February 2024.

9 ‘List of the World’s Largest Countries and Dependencies by Area’, Britannica, www.britannica.com/topic/list-of-the-total-areas-of-the-worlds-countries-dependencies-and-territories-2130540, accessed 25 February 2024.

10 ‘Global De-Dollarization Takes a Pause, Embattled Euro Gives Room for Asian FX’, ING (2024), https://think.ing.com/articles/global-dedollarization-takes-a-pause-yuan-challenged-by-the-yen/, accessed 22 February 2024.

11 Chris Turner, Dmitry Dolgin, and James Wilson, ‘BRICS Expansion and the Dollar: Would a Larger Bloc Mean Faster De-dollarisation?’ THINK Economic and Financial Analysis (August 2023), https://think.ing.com/reports/brics-expansion-and-the-dollar-would-a-larger-bloc-mean-faster-dedollarisation.

12 Turner, Dolgin, and Wilson, ‘BRICS Expansion and the Dollar’.

13 ‘Red Sea, Black Sea and Panama Canal: UNCTAD Raises Alarm on Global Trade Disruptions’, United Nations, https://unctad.org/news/red-sea-black-sea-and-panama-canal-unctad-raises-alarm-global-trade-disruptions, accessed 25 February 2024.

14 Chris Menon, ‘Could BRICS Countries Introduce Their Own Currency for International Trade?’, The Payment Association (December 2023), https://thepaymentsassociation.org/article/could-brics-countries-introduce-their-own-currency-for-international-trade/.

15 Serkan Arslanalp, and Chima Simpson-Bell, ‘US Dollar Share of Global Foreign Exchange Reserves Drops to 25-Year Low’ IMF.org (May 2021), www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2021/05/05/blog-us-dollar-share-of-global-foreign-exchange-reserves-drops-to-25-year-low, accessed 2 June 2024.

16 ‘Gold Reserves by Country’, World Gold Council, www.gold.org/goldhub/data/gold-reserves-by-country, accessed 26 February 2024.

17 ‘Global De-Dollarization Takes a Pause’.

18 Central Bank of Brazil, International Reserves Management Report (2023), www.bcb.gov.br/content/financialstability/irmr/relatorio_anual_reservas_internacionais_en_2022.pdf, accessed 2 March 2024.

19 Greene, ‘The Difficult Realities of the BRICS’ Dedollarization Efforts’.

20 Owen Walker, and Cheng Leng, ‘Chinese Lenders Extend Billions of Dollars to Russian Banks after Western Sanctions’, Financial Times (3 September 2023), www.ft.com/content/96349a26-d868-4bd1-948f-b17f87cc5c72.

21 ‘Решетников заявил, что доля национальных валют в торговых расчетах РФ и Китая достигла 90%’, TASS (2023), https://tass.ru/ekonomika/18783091, accessed 3 March 2024.

22 Tamar den Besten, Paola Di Casola, and Maurizio Michael Habib, ‘Geopolitical Fragmentation Risks and International Currencies’, The International Role of the Euro (European Central Bank, 2023), www.ecb.europa.eu/press/other-publications/ire/article/html/ecb.ireart202306_01~11d437be4d.en.html, accessed 3 March 2024.

23 Project mBridge is a collaborative effort that aims to foster the use of the UAE’s central bank digital currency (CBDC), the Digital Dirham, for cross-border transactions.

24 Henry Sender, ‘Iran Accepts Renminbi for Crude Oil’, Financial Times (7 May 2012), www.ft.com/content/63132838-732d-11e1-9014-00144feab49a, accessed 4 March 2024.

25 Greene, ‘The Difficult Realities of the BRICS’ Dedollarization Efforts’.

26 Greene, ‘The Difficult Realities of the BRICS’ Dedollarization Efforts’.

27 Bank for International Settlements, ‘OTC Foreign Exchange Turnover in April 2022’, Triennial Central Bank Survey, Monetary and Economic Department, BIS.org, www.bis.org/statistics/rpfx22_fx.pdf, accessed 7 March 2024.

28 Bank for International Settlements, ‘OTC Foreign Exchange Turnover in April 2022’.

29 World Integrated Trade Solutions (WITS), ‘China Product Exports by Country in US$ Thousand 2021’, https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/CHN/Year/LTST/TradeFlow/Export/Partner/by-country/Product/Total, accessed 26 February 2024.

30 Greene, ‘The Difficult Realities of the BRICS’ Dedollarization Efforts’.

31 Greene, ‘The Difficult Realities of the BRICS’ Dedollarization Efforts’.

32 European Central Bank, When Did the Dollar Overtake Sterling as the Leading International Currency? Evidence from the Bond Markets, Working Paper Series No. 1433, www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1433.pdf, accessed 10 February 2024.

33 ‘Global De-Dollarization Takes a Pause’.

34 ‘Global De-Dollarization Takes a Pause’.

Related articles: