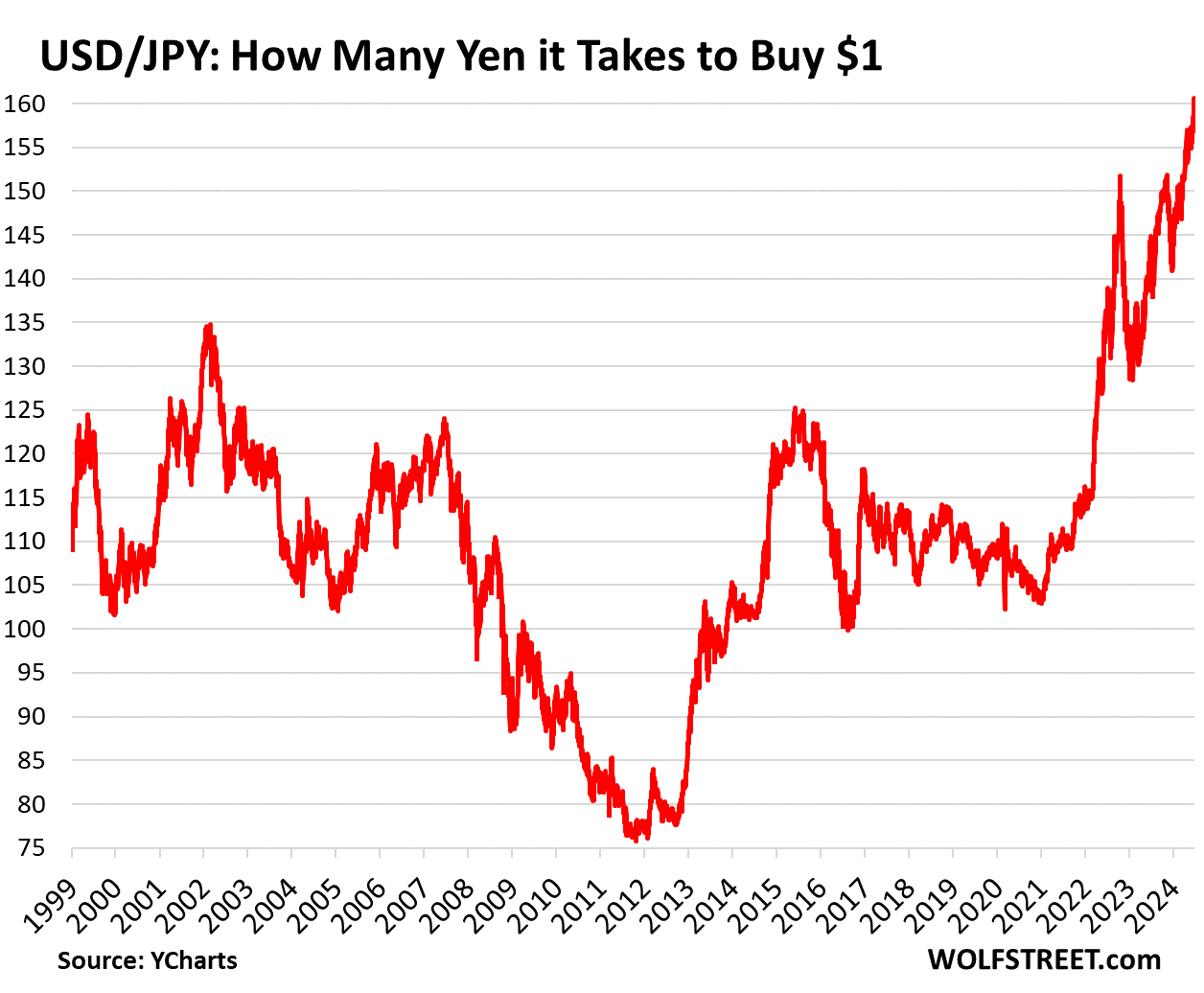

Yen Drops to 161 against USD. -34% since 2020, -53% since 2012. Currency Collapse Comes to Mind. Bank of Japan Finally Gets Nervous about its Crazed Monetary Policies

A collapsed yen is not good for Japan, which has had a trade deficit for years. And it contributed to energy price shocks.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET:

The yen dropped to ¥160.8 to the USD today, the weakest since 1986, despite endless jawboning by Japanese authorities – including today by vice finance minister and currency chief Masato Kanda – and some massively costly and ultimately useless market interventions.

Since June 2020, the yen has plunged by 34% against the USD. Since January 2012, when the Bank of Japan’s crazed monetary policies began under Abenomics, the yen has plunged by 53% against the US. These are massive movements for a developed-country’s currency (data via YCharts).

Jawboning and costly interventions were useless.

In April and May, Japanese authorities blew $62 billion in the foreign exchange market to prop up the yen and to prevent if from falling through the 160 level, and it had a temporary effect, and now the yen fell through that level anyway. It seems authorities have given up on holding the 160 line and may have moved the marker for interventions further north, maybe to 165.

Kanda, the currency chief, said today that he has “serious concerns” about the plunge of the yen and that they’re “closely monitoring market trends with a high sense of urgency,” Bloomberg reported. And he added, “we will take necessary actions against any excessive movements.” But apparently there were no excessive movements, and they did nothing.

Earlier this week, Kanda had said that authorities were ready to intervene 24 hours a day. But nothing happened. Finance minister Shunichi Suzuki had said that authorities were closely monitoring the currency markets and would take all possible measures if needed, and none were needed or taken, it seems.

The problem for the yen is the Bank of Japan’s reckless monetary policy, and that cannot be resolved by blowing tens of billions of dollars in ultimately useless market interventions

A collapsed yen is not good for Japan.

The time when Japan had huge trade surpluses, and a weaker yen would have been beneficial to some extent, are long gone. The country has had a trade deficit for most years since 2011, including for the past three years in a row. Japan imports all kinds of goods, including much of its energy commodities, and the weak yen makes those imported goods a lot more expensive, which has contributed substantially to the massive energy price shocks that have occurred in Japan.

The government decided to subsidize energy costs at the wholesale level to spare consumers some of the pain. Those subsidies are now expiring; some were allowed to expire, others have been extended through the rest of the year. And all that too was costly.

Japan’s global companies with revenues and profits overseas benefit on paper by being able to translate revenues and earnings from dollars and euros into lots of crushed yen, for their yen-denominated financial reports. For example, most Japanese cars that Americans can buy are manufactured in the US and Mexico. These sales generate dollar-revenues and dollar profits for the Japanese automakers that they then translate into crushed-yen-denominated financials for domestic consumption.

Companies that export from Japan also benefit. But companies that import, including components and supplies, get hit by surging costs. And Japan imports more than it exports, so on balance, it’s a negative.

At the same time, inflation — not only high energy prices in Japan but also spiking prices of essential services that companies pay for in Japan — are eating into domestic profit margins.

Sure, tourism is now booming, attracting budget-traveler crowds from around the globe. And so the Japanese people get to enjoy them, instead of traveling overseas themselves with their crushed yen.

The BOJ’s painfully too-little-too-late.

The yen started skidding lower in 2021, the year when other central banks started hiking interest rates, or were talking about hiking interest rates, from 0% or negative rates, and they began tapering QE and were preparing the markets for QT, as inflation was rearing its ugly head just about everywhere, even in Japan.

But the Bank of Japan was steadfast in 2021, 2022, and 2023 in its refusal to undo its negative interest rates and end yield-curve control and QE, and start QT, and thought somehow that inflation would just vanish and that other central banks would cut rates pronto. And so the yen got bludgeoned.

In 2024, the BOJ has begun to reverse course, but in a painfully too-little-too-late way, and the yen just keeps getting bludgeoned.

At the policy meeting in March, the BOJ hiked by a minuscule 10 basis points to 0% and effectively ended yield-curve control, and ended other aspects of its QE.

Since then, its holdings of Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) have dipped just a tad as it purchased less in JGBs than matured. Its holdings of commercial paper and corporate bonds fell, and its holdings of equity ETFs and J-REITs had already been flat since 2022 (we discussed the BOJ’s balance sheet here).

Following its policy meeting on June 14, the yen took another hit when the BOJ failed to raise its policy rates, and announced that QT would begin immediately after its next meeting at the end of July, without providing details. BOJ governor Kazuo Ueda said at the press conference that the reduction of the BOJ’s bond holdings would be considerable. “We are proceeding carefully but it doesn’t mean that we will reduce only by a small amount,” he said. He also indicated that the BOJ might do another rate hike at the July meeting.

All this is painfully slow, as the world grapples with inflation, which this year has begun rising again in Japan, in the US, in Canada, in Mexico, in the Euro Area, in Australia…

The BOJ had gotten away with its crazed monetary policies for so long – until it suddenly didn’t. Which must have come as a shock. It is now lining up more significant steps (rate hikes and considerable amounts of QT) to move away from these crazed monetary policies. The central banks of Mexico and Brazil knew how to protect their currency in 2021 and 2022 in face of inflation and the Fed’s expected reaction to inflation: They started with massive rate hikes in 2021, pushing their policy rates into the double digits by 2022, and their currencies did very well against the USD, even as the yen plunged.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()