It’s been a splendid run for the market — so emphatically great that in just the first three months of the year, the S&P 500 climbed to record highs on 22 separate days.

Most people who have looked at their stock portfolios this year have had the pleasant experience of seeing increases in their holdings, and countless news reports and analyses from financial gurus have talked optimistically about the market’s powerful upward momentum.

But what most reports and commentary haven’t pointed out is that because inflation has also climbed sharply over the last few years, the value of stock prices has eroded, along with nearly everything else in the economy. When you factor in inflation, the stock market did not actually reach new heights.

That’s finally changing, with the market’s gains outpacing the ravages of inflation sufficiently to push real stock valuations close to a new peak, according to calculations by Robert J. Shiller, the Yale professor and Nobel laureate in economics. In a phone conversation, he said, “On a monthly, inflation-adjusted basis, it does appear that the S&P 500 now is right around a record high.”

Professor Shiller can’t be more precise for another month or two because the Consumer Price Index is calculated retrospectively, while stock prices are virtually instantaneous. On his Yale website he posts monthly inflation-adjusted stock, bond and earnings data. The last inflation-adjusted peak for the S&P 500 was in November 2021.

We’re certainly close to that inflation-adjusted peak — or may have already reached it — and that’s a big deal. It means that the market is, at last, starting to make real records, pulling stock returns ahead of the eroding effects of inflation.

It’s also a sobering reminder: Despite all the good news in the stock market over the last year or so, once you factor in inflation it really hasn’t gone anywhere since late 2021. Money illusion — the common human failure to pierce the veil imposed by inflation — has obscured that reality.

What’s more, the rally in the stock market isn’t entirely a good thing for truly long-term investors. Recent gains come after a long, periodically interrupted trend of rising stock prices, which have outstripped increases in corporate earnings. This reminds Professor Shiller of the rallies of the 1920s and the dot-com boom, which both ended badly. When prices get too far ahead of earnings, there will eventually be a reckoning — and, he says, there’s a good chance that U.S. stock market returns will be lower over the next decade than the last one.

That makes it imperative for long-term investors to diversify their holdings. He takes the same investing approach recommended in this column: using cheap index funds to hold the entire stock and bond markets, and hanging in for decades.

Some Good News

Inflation aside, the start of the year has been brilliant for stock investors. Most quarterly portfolio updates will reflect recent gains.

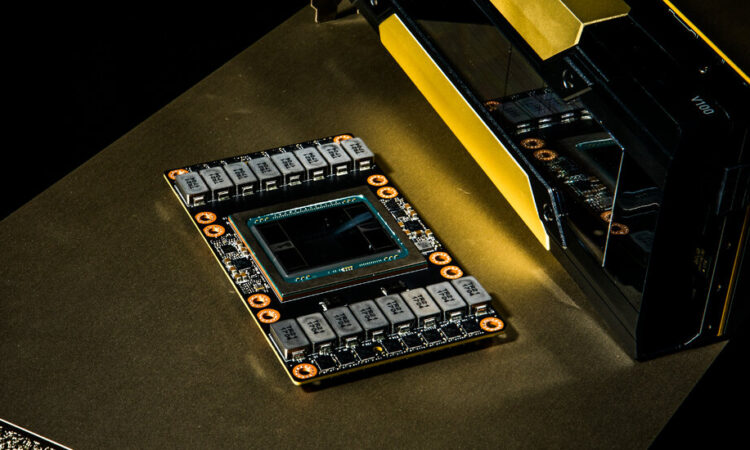

Tech stocks like Nvidia, the chip designer, have been shooting straight into the stratosphere, fueled by enthusiasm for artificial intelligence. But the rally in the stock market has also been broad-based, with the run-of-the-mill mutual fund and exchange-traded stock fund posting strong returns for the first quarter.

For bond funds, it was a different story. Interest rates rose as it became clear that the economy was strong, inflation was persistent and the Federal Reserve would not cut rates until later this year, if then. Bond prices and interest rates move in opposite directions, and mutual fund and E.T.F. bond returns are a combination of yields (interest rates) and price changes. In the first quarter, most bond funds eked out gains, but barely.

Here are some representative, average results from Morningstar, the independent financial services company, for stock and bond funds, including dividends, through March 31:

-

U.S. stocks, 8.7 percent for the quarter and 24.1 percent over 12 months.

-

International stocks, 4.3 percent for the quarter and 11.8 percent over 12 months.

-

Taxable bonds: 0.7 percent for the quarter and 5.6 percent over 12 months.

-

Municipal bonds, 0.4 percent for the quarter and 3.9 percent over 12 months.

Among domestic funds specializing in sectors of the stock market, technology funds were a standout, with an average return of 13.6 percent for the quarter and 42.6 percent over 12 months.

Remarkable Gains

It’s always possible to do better than average, by putting all your money into the best performing stock or stocks. Risk takers who went all in on Nvidia stock, for example, gained 82.5 percent for the quarter and 235 percent over the 12 months through March.

Why stop there? Since Oct. 19, it’s been possible to buy an E.T.F. — the T-Rex 2X Long NVIDIA Daily Target E.T.F. — that uses leverage and derivatives with the aim of producing double the return of Nvidia stock. It did even better than the stock in the first quarter, with a gain of 205 percent. But if Nvidia falls for an extended stretch — and, like every other stock in history, it will — your losses will be staggering.

Nvidia produces solid and growing earnings. The fundamental issue for investors is whether its earnings can grow fast enough to justify its share price.

Bitcoin is another matter. Its value is based only on what people think it’s worth.

Since Jan. 11, it’s become easier for fund investors to trade in the cryptocurrency. That’s when new E.T.F.s that track the Bitcoin spot price began trading. One of these funds, the iShares Bitcoin E.T.F., gained 52 percent through March. Not bad!

But Bitcoin could fall just as easily and make your money evaporate. That happened in 2022, when the enormous fraud behind FTX was uncovered. Customers lost billions of dollars and Sam Bankman-Fried, the founder of the cryptocurrency exchange, was sentenced last month to 25 years in prison. Speculative appetites diminished in 2022 but they evidently have become ravenous again.

I would love to have tripled my wealth over the last 12 months, which would have happened if I had placed it all in Nvidia stock — or increased it by more than 50 percent, which the Bitcoin E.T.F.s could have accomplished in little more than two months.

But those moves seem far too risky for money that I’m going to need one day. Instead, I took the long-term, diversified approach, which doesn’t look nearly as good over the short-term.

My personal returns, split between stocks and bonds, are close to those reported by the pure index Vanguard Life Strategy Moderate Growth Fund, which contains roughly 60 percent stock and 40 percent bonds. It gained just 4.4 percent for the quarter. But over the 12 months through March, it returned 14.2 percent. And since its inception in 1994, it has returned 7.4 percent annualized — which means the value of the investments has roughly doubled every decade.

Even this long-term diversified approach entails risk, however, and shouldn’t be attempted by those who are unable or unwilling to withstand losses.

In our conversation, Professor Shiller reminded me that while the stock market has always, eventually, bounced back, there’s no guarantee that it always will. And his research shows that at current valuation levels, the U.S. market is overpriced on a historical basis, given the level of corporate earnings.

That doesn’t necessarily mean imminent trouble. But his findings on the relationship between prices and earnings — for which he was awarded a Nobel — suggests that the S&P 500 is less likely to produce stellar returns over the following decade than was the case when the market bottomed in early 2020, during the Covid-19 recession. Global markets outside the United States have better valuations now and are more likely to excel. These statements are probabilities, not forecasts. You may not want to trade on them, but keep them in mind.

In some ways, he said, the current period reminds him of the boom of the 1920s. The excitement about artificial intelligence is reminiscent of popular enthusiasm over the innovation of the day back then — which, he said, was radio. “RCA was the big stock then,” he said. “That’s what I think of when I look at Nvidia.”

Like the rest of the market, RCA shares crashed in 1929. (The company survived and prospered in many incarnations, before becoming part of General Electric in 1985.)

While there’s no dependable way of forecasting market crashes or long-term returns, Professor Shiller said, it’s wise to be cautious with the money you count on.

That argues for holding high-quality corporate and government bonds, which are likely to retain value in the worst of times. Diversify globally and avoid the temptation to go all-in on riskier investments, even if they may lead to greater short-term gains.

Now that we’ve gotten back to late 2021 levels, I’m sticking with this slow and relatively steady approach. It’s worked for decades. With a little luck, it still will.