How a ‘halfway-pendulum’ approach to stakeholder capitalism helped Japan’s stock market reverse decades of losses

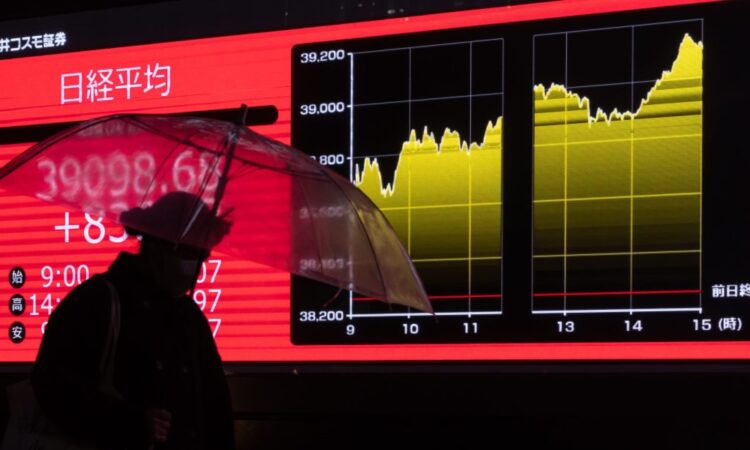

Though the Japanese way had come to be seen as a global standard for modern capitalism in the 1980s, it caved dramatically and enduringly during the 1990s. But after flatlining for nearly two decades, the Nikkei 225 Index quadrupled in value from 2009 to 2024. To understand what has created this turnaround, we interviewed more than 100 Japanese business leaders from 2019 to 2023.

What we discovered is that business practices at some Japanese firms are morphing into what can be deemed a new model, retaining what has long been conventional, and at the same time adopting what had once seemed heretical—a new leadership model we call Resolute Japan.

The dual incorporation of past precepts and new tenets that define the Japanese resolute model have also been fostered by an executive mindset that absorbs yet also reinterprets offshore governance practices. Rather than embracing Western tenets wholesale, firms have selectively borrowed from abroad while keeping features of their own doctrine in areas ranging from management transparency and director independence to stakeholder diversity and successor selection.

Consider one of the most pronounced differences in how executives of publicly traded companies in Japan and the United States view their obligations to stakeholders in years past. Drawing on a survey conducted in the mid-1990s of 78 British, 48 French, 105 German, 68 Japanese, and 83 U.S. companies, a university researcher (Yoshimori, 1995) found that three-quarters of the American executives reported that in their company, “shareholder interest should be given the first priority.” By contrast, virtually all—97%—of the Japanese respondents affirmed that “the company exists for the benefit of all stakeholders.”In an equally striking national difference, when asked if a “CEO had to choose between maintaining a dividend or firing a large number of employees,” most American managers would pay the dividend rather than retain the employees, but virtually all of the Japanese would keep the employees and withhold the dividend.

The same mindset appears today in the national differences between company total return ratios: The sum of dividend payments and share buybacks as a percentage of net income averaged 83% for U.S. companies in 2022, but just 29% for Japanese companies. It should be noted that a Japanese tradition, largely unknown in the United States, calls for company gift-giving to shareholders, marginally mitigating the national disparity in prioritizing shareholders for financial benefit. In Japan, more than a third of the country’s listed companies bestow “special gifts”—their own products or services—on their shareholders.

Over the years, that gap has moderated—both because of the movement of Japanese principles toward those of the United States and the movement of American principles toward those of Japan. The latter has been best exemplified in the remarkable about-face by the premier association of American CEOs, the Business Roundtable. In a clarion call in 1997, it declared that “the principal objective of a business enterprise is to generate economic returns for its owners.” Yet in a revised declaration in 2019, the blue-chip U.S. executives now declared that the purpose of a business enterprise is instead to deliver value to all of its “stakeholders,” not only the owners. Equally deserving are its customers, employees, suppliers, and communities.

Seeking to pull Japan’s pendulum in precisely the opposite direction, and closing the global gap from the other end, the Asian Corporate Governance Association, a non-profit Hong Kong-based advocacy and research group, issued a call in 2008 for greater dedication to shareholder returns, not just employee gains. The association declared that Asian companies were too fond of “stakeholder governance” and shareholders were too passive in demanding more rights.

The Tokyo Stock Exchange, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, the Financial Services Agency, and the Japan Business Federation (known as Keidanren) embraced the call, though they left most of the changes to company executives, corporate directors, and exchange managers rather than policymakers. Keidanren said, for instance, that companies should be allowed to voluntarily improve their shareholder governance, though no one best way should be imposed for doing so. The Financial Services Agency called for exchange authorities to focus more on shareholder value, less on other values. The national government called for the creation of “financial and capital markets comparable to those in New York and London.”

The Japanese government stepped forward more directly in 2015 as the Financial Services Agency, a national regulator overseeing banking, insurance, and securities, issued a landmark call to action. Its corporate governance code urged companies to replace their inward-looking governance model in favor of an outward focus on shareholders. It called for more independent directors, and Japanese companies complied in spades. According to a 2023 report by the Japan Institute of Directors, many Japanese listed companies have implemented shareholder-friendly measures in the form of increasing the number of outside directors. In the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange—listing the country’s premier companies—the number of firms that have appointed independent outside directors rose from 32% in 2010 to 99.7% in 2019. Companies with independent directors accounting for more than one-third of the board rose from 16% in 2015 to 96% in 2023. Compared to firms in the United Kingdom and United States, however, outside directors are still less represented on Japanese boards. Among companies listed on the United Kingdom’s FTSE 100, outside directors constituted 78% of the boards, among companies in the United States’ S&P 500 index 87%, but among Japan’s TOPIX firms, still only 48%.

Although such changes, as limited as they are, point in the direction of American governance norms of shareholder supremacy, research on their impact on financial performance has yielded ambiguous results to date—some studies confirming favorable consequences for shareholder wealth, but others less so. While pulling Japanese companies more toward the West’s primacy on investor value, directionally right for building the resolute model, the performance consequences for investors have been more equivocal.

Some studies, for instance, report a correlation between the introduction of outside directors and improved corporate performance but others detect none. Still, there are signs of life: Among large publicly traded Japanese companies, the ratio of dividends to shareholder equity rose from 1.9% in 2012 to 2.4% in 2017.

Our executive interviews revealed a healthy skepticism about the intent and impact of the governance reforms, a cautionary warning from those who personally witness the inside workings. The addition of independent directors is directionally right so far, but the boardroom mindset still has a long way to go. “About 10 years ago, academics and the media began to make recommendations about corporate governance and outside directors,” explained Shinichiro Ito, board chair of ANA Holdings, Japan’s largest air carrier. “But I think many companies didn’t really understand what they meant.”

While board meetings are better planned, company directors are more vocal, and decisions more transparent, tangible payoffs have proven elusive. “I don’t feel that the governance reform through the introduction of the Governance Code has particularly improved our management,” Ito found. “The Corporate Governance Code is based on the premise that human nature is fundamentally depraved,” Ito observed, “and I have my doubts whether that will really suit (Japan).” As a result, the ANA chief concluded, “many managers may secretly believe that Japanese-style good-natured management is good enough for them.”

When we asked “who are the stakeholders that the board considers most significant,” just a tiny fraction of the Japanese chieftains (2%) deemed their owners as the “most significant” of the varied stakeholders, the north star for publicly traded companies in the United States. By contrast, more than four out of five Japanese executives designated all constituencies as “most significant” for them.

Though acknowledging that their company should be more owner-focused, virtually all of the interviewed executives also said that their boards still served an array of interested parties, particularly employees. Company leaders nominally accepted the resolute reformulation, but still accepted their nation’s long-standing conventions. “As a board of directors, we have to say that shareholders are important,” affirmed one director, but in fact their importance is little greater than that of others. So deep is the philosophy that many of the executives reported that their governing board had never even discussed which stakeholders, if any, to prioritize, simply taking it for granted that it was all rather than one.

Even when pressed in our interviews, virtually all of the company leaders still said they saw their world through a multi-holder lens, and some of them continued to say so publicly. Asahi Breweries, for instance, proudly declared it favors all stakeholders—customers, employees, society, business partners, and shareholders—and Calbee Inc., a large snack food maker, went even further, declaring that it ranked customers and business partners first, then employees and their families, then society, and, only then, shareholders.

Japan’s new resolute model’s halfway pendulum has thus prevented complete subordination of non-shareholders to investor dominance, but it has nonetheless brought owners into the room far more than in the past.

Kentaro Kawabe, the CEO of Z Holdings (an internet company that owns Yahoo! Japan), makes the half-pendulum case for not only explaining company purposes but also hearing investor voices. A previous president of Yahoo! Japan, Manabu Miyasaka, had told the younger Kawabe that he should actively communicate with investors and analysts. “When I asked him why, he replied, ‘Smart people from all over the world analyze our company thoroughly for free and give us all kinds of advice on what to do and what not to do.’”

Adapted from Resolute Japan: The Leaders Forging a Corporate Resurgence, by Jusuke J. J. Ikegami, Harbir Singh, and Michael Useem, copyright 2024. Reprinted by permission of Wharton School Press.