The stock market was meant to grow your money. That’s a great and exciting concept when you’re in your 20s through your 50s and you have lots of time to work, save and invest, recover from market dips and watch your funds surge during a bull market run.

It was not, however, created to provide a family or investor guaranteed lifetime income.

That’s an important difference for those nearing retirement to consider when working with a financial planner to create a diversified retirement income strategy.

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free E-Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more – straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice – straight to your e-mail.

When people reach their 50s and 60s, it’s time to look at their money and risk differently. There’s less time to recover from a down market, and when the paychecks stop, the money they’ve worked so long and hard to save and invest needs to last the rest of their lifetime.

Again, stocks don’t guarantee that, yet the most popular option I see financial advisors using regarding retirement income planning relies mostly on stock performance. People put the majority of money they’ve saved over decades of working into their stock market portfolio, hoping it will last.

Market volatility requires portfolio versatility

The stock market is volatile, perhaps more so than ever before. In 2022, the S&P 500 suffered its worst first half since 1970, sinking 20.6% from January through June. It finished the tumultuous year off 19.4%.

Then, in 2023, most experts predicted the market would perform poorly. They were wrong. The S&P had a stellar year, closing up 24%. No one really knows how the market will perform, which means it’s risky to try to “time” it.

Sure, at first glance, given the historical decade-to-decade growth of the market, putting most of your money in there may not seem like pushing too many of your chips to the middle of the poker table. But in your 60s, 70s and beyond, the perspective changes, or should, when sequence of returns risk can become more damaging. That might make you reconsider how you divide your stocks-to-safer-funds ratio when creating a retirement income plan. Sequence of returns risk means that the order and timing of poor investment returns can severely impact your retirement savings and how long they last.

Primarily for that reason, people would be wise to consider being less weighted on stocks in retirement while having reliable sources of income that are not subject to sequence of returns risk, such as: bank certificates of deposit (CDs), fixed annuities, bonds, life insurance, real estate (if you own investment properties) or real estate investment trusts (REITs), along with Social Security and pensions.

I’m not saying focusing mainly on the stock market for retirement income won’t work; there have been times when it has. But it matters, really matters, how the stock market performs and when you take the money out. It matters more when you’re in the early years of retirement than it does later in retirement.

For example, if someone needs $1,000 a month from their stock portfolio in a given year and they sell $12,000 worth of those assets, that’s a problem if the market is down at that time. That’s the worst thing you can do — sell stocks at a loss when taking the money out. You would be realizing a loss every time that happens.

Some people will say they survived the Great Recession of 2007-2009 because the market bounced back, but that’s because they had plenty of working years left. The difference in retirement is you’re no longer adding money to those accounts. Instead, you’re pulling money out, and it will take longer for your portfolio to recover.

The saga of Steve and Bill

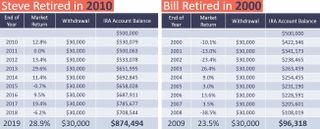

Pulling money out of the market at different times can result in dramatically different outcomes. The following story illustrates how the early years of retirement could be impacted. Imagine two brothers, Steve and Bill. Each saved $500,000 for retirement. Each decided to withdraw the same amount from their stock portfolio each year of retirement — $30,000. The main difference: Steve retired in 2010 when stocks were entering an epic bull market. Meanwhile, Bill retired in 2000. Ten years into Steve’s retirement, his balance had grown from $500,000 to $874,494.

But Bill’s timing wasn’t so good. When he retired and began withdrawing funds, the market fell the first three years (in 2000, 2001 and 2002), so by 2009, his $500,000 had shrunk to $96,318. It created the effect of a snowball rolling downhill, and he could not push it back up the hill.

Note: These hypothetical examples are provided for illustrative purposes only. Source: finance.yahoo.com.

(Image credit: Courtesy of Chris Morrison)

Taking a substantial market loss early in retirement can have a huge potential effect on how long your money lasts. A major market drop causes some people to tap into their portfolios when they’re losing value, giving them fewer assets and less ability to bounce back during a recovery.

If you go to bed each night heavily invested in stocks and don’t know if you’re going to end up like the first brother or the second brother, it might behoove you to be open-minded to other options that aren’t subject to sequence of returns risk.

Don’t fly blind

Some financial firms use Monte Carlo simulation models to stress-test their clients’ plans. A client has their portfolio uploaded into a computer software program that runs through many market scenarios, and it spits out a professional-looking report. Let’s say that report projected, as it did for someone I know, that the likelihood for success was high — 87%. That sounds pretty safe, but remember, this is someone’s retirement money we’re talking about, and it needs to last them through retirement.

I tell this story in workshops and seminars: In a couple of weeks, I’m going to get on a plane. Let’s say the pilot gets on the loudspeaker, gives us the estimated flight time and says the weather is good but there may be some light turbulence, and we have an 87% chance of getting there alive.

At that point, I’m going to unbuckle my seat belt, get off the plane and find a different airline.

Things may go smoothly in the market, but what if, a couple of years into your retirement, it crashes and most of your money is tied up in it?

Consider your less risky options. Interview multiple advisors if one or more are telling you to stay mostly in stocks. Don’t let yourself be too vulnerable to sequence of returns risk.

Dan Dunkin contributed to this article.

The appearances in Kiplinger were obtained through a public relations program. The columnist received assistance from a public relations firm in preparing this piece for submission to Kiplinger.com. Kiplinger was not compensated in any way.

Insurance products are offered through the insurance business The Legacy Retirement Group. The Legacy Retirement Group is also an Investment Advisory practice that offers products and services through AE Wealth Management, LLC (AEWM), a Registered Investment Adviser. AEWM does not offer insurance products. The insurance products offered by The Legacy Retirement Group are not subject to Investment Advisor requirements. This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant as investment advice or a recommendation to engage in any investment or financial strategy. Investment and financial decisions should always be made based on your specific financial needs, objectives, goals, time horizon and risk tolerance. Please consult with a professional regarding your personal situation. 2611061 – 9/24