There’s nothing like a looming Budget Day to gee up or stall home sales in the UK. One month out, with the UK chancellor Rachel Reeves eyeing taxes on high-value homes, owners are anxious.

“Better the devil you know,” says Hamptons estate agent Joanna Cocking of her clients, who she says are rushing to cut listing prices by up to 25 per cent to complete sales. “Many buyers are bringing home moves forward in case changes increase the costs associated with purchases or sales,” adds Robin Chatwin, head of south-west London sales for Savills.

Last week I wrote about the rise of price cuts to homes on the market because of sellers’ propensity to overvalue. Until then I didn’t fully understand how delusional some homeowners can be when it comes to valuations — even when faced with concrete statistics about how much harder, in today’s lacklustre market, an overvalued home is to sell.

I started to wonder about the flip side: could Reeves’ mooted changes burrow into the psyche of a select few homeowners, such that a high valuation becomes something they are wary of? At least, that is, until they sell.

The burden of any potential property tax hikes looks set to fall on a small group of homeowners. Summer news that Reeves had ordered Treasury officials to examine reforming property tax coalesced around two possible changes: a “mansion tax” on capital gains for homes over £1.5mn, and an annual tax to replace stamp duty — payable upon sale — starting at £500,000, increasing again at £1mn.

Stamp duty currently comprises the lion’s share of moving costs, dwarfing agents’ and legal fees; abolishing it should free up people to move home more frequently. In its place, rumoured annual tax charges of 0.54 per cent per year on the value over £500,000, rising to 0.81 per cent over £1mn. So, no matter how many times you move, if it was to another home of the same value, the bill would be the same.

But if that tax is based on the value of a home each year, surely some are likely to challenge that valuation, and the methodology — even angling for a down valuation.

There are currently few mood-boosting sports for homeowners more compelling than watching house prices on their street go up. Even when those other homes have a kitchen extension, the garden is bigger, the interiors newer and the main road further away — it’s an easy delusion that the differences are cosmetic.

If there was a knock-on effect from local price rises that increased the property tax due, might owners, rather than looking for evidence a home is appreciating, instead search just as zealously for evidence it was staying the same, or reducing? If an identical home next door sold for a premium, might they now strain to find 100 reasons it was better than theirs?

When council tax bands were introduced following valuations in 1991, more than half a million homeowners challenged that their homes were overvalued and should be in a lower band, paying less tax.

And, on the basis of current evidence for the accuracy of government valuations, there would be plenty to challenge. More than half of English homes are sitting in the wrong band, according to research by the FT — Londoners especially have homes that are undervalued in the current system. (That means large valuation errors: band G, for example, spans homes now valued between roughly £880,000 and £1.8mn.)

In the US, revaluations are conducted every year in some states, including Florida. In NYC in 2023 appeals were lodged for reductions in valuations for 206,000 homes; one in six succeeded. “Challenging valuations has become a huge cottage industry,” says Jonathan Miller, a real estate professor at Columbia University in New York. Owners employ surveyors to provide lower estimates, while lawyers are enlisted to argue the case.

Valuations would be a closely scrutinised process. The frequency and the need to keep costs low means automated models like those employed by Rightmove and Zoopla could provide a big role. This would certainly make the hobby of having “a quick look” at your home price online much more loaded.

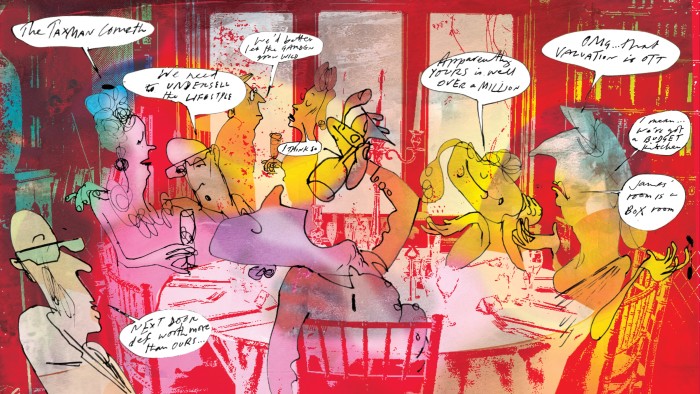

If home improvements impacted valuations owners would be less smug about them. That kitchen extension or loft conversion — that pride and joy — would not be quite the same centrepiece of dinner-party tours if it adds to the annual tax bill.

And what if homeowners have to self-report such price pick-me-ups? Currently, only when a home is sold can planning and building records be checked and its value reassessed to see if the council tax band should be updated. Who’d fess up before then? Meanwhile, improvements made under permitted development rules don’t require planning permission and, while the council logs the required building control records, these are typically not publicly available. A world in which home improvers hope the changes fly under the council’s radar doesn’t seem far-fetched.

Such variations in homes mean that, “At the top of the market automated valuation models work less effectively,” says Cook. But I’d argue that it’s not only at the top of the market: the valuation on Zoopla for my three-bed Victorian terraced flat in London is more than double what I just sold it for.

“Even when surveyors are employed, working at scale means local variations get missed,” says Gerald FitzGerald, a chartered surveyor who values country homes for Savills. He points to the sort of errors made by surveyors who conducted council valuations en masse in 1991. Homes close to a busy road were often undervalued; “exception homes, like gatehouses that are difficult or impossible to sell independent of the main house they were attached to” often ended up overvalued.

Martin Lewis of Money Saving Expert, who has been campaigning against inaccurate valuations since 2007, advises punchy action. First, establish if a home is in the wrong band (by comparing bands for comparable homes on the same street or nearby), then estimate what that home was worth in 1991 — to establish that it is your home, not all the others, that is in the wrong band. The website provides a calculator to help establish 1991 valuations (moneysavingexpert.com/reclaim/council-tax-bands-change).

All this conscientious price pessimism might evaporate, of course, as soon as people wanted to sell their homes, when high prices would be good news again. It’d be a strange kind of behaviour, lowballing values, putting off or hiding improvement — until it came to sell.

Meanwhile, although a mansion tax risks undoing much of the good to come from scrapping stamp duty (downsizers, for example, might dread crystallising a big tax bill on sale), it probably wouldn’t see people wanting their home values to fall. “That feels very unlikely,” says Iain McLeod, head of private clients at wealth manager St James’s Place. After all, paying 24 per cent on a gain (the current CGT rate for higher-rate tax payers) still leaves you with 76 per cent of the gain to enjoy.

But, he points out, for owners of high-value homes sitting on losses rather than gains, losses would offer the chance to offset against gains elsewhere, such as investment sales to release a lump sum of cash for school fees — reducing tax bills. Homeowners might not be seeking a loss, but there’d potentially be an upside.

McLeod doubts people would spot the opportunity immediately. “There is a general malaise when it comes to taking substantive action around tax planning, people take time [even] when presented with the facts,” he says.

So much for being presented with the facts: rumours are all we have to go on. Even these are changing constantly. When I started thinking about these issues, the burning question seemed to me how council tax reform would feel to owners of high-value homes.

Then at the Labour party conference in September, housing secretary Steve Reed ruled out revaluing council tax bands. Bullet dodged? I’m not so sure. The chancellor’s £30bn black hole still looms. And as November 26 approaches, homeowners can only wait, speculate and worry.

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ft_houseandhome on Instagram