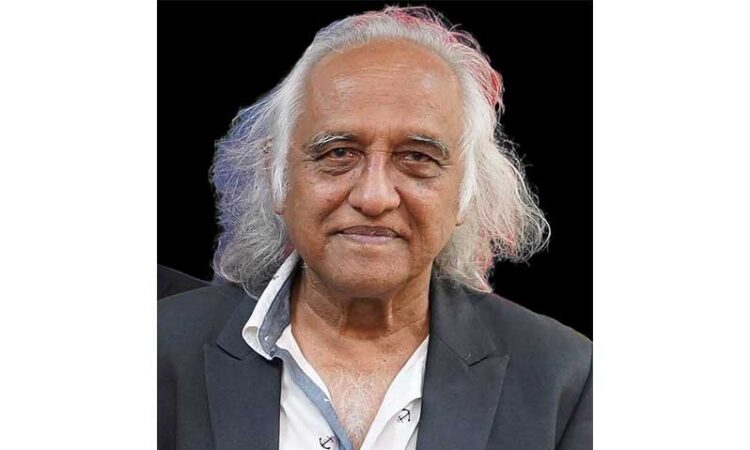

THE Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) on Tuesday commenced and concluded hearing arguments in the matter involving the 25-year-old action brought by Cara Investments Limited against Chartered Accountant and attorney-at-law Christopher Ram and the Bank of Nova Scotia over the sale of Hotel Tower. The court has since reserved its decision.

The conflict originated in 1999, when the bank appointed Ram as Receiver/Manager of the then-struggling Georgetown establishment. From the date of his appointment, Ram assumed control of the hotel’s assets and subsequently initiated a Request for Proposals (RFP) inviting bids for its purchase. The public notices advertising the RFP made it clear that the receiver had broad discretion in managing the process, including the power to halt it entirely before any final agreement was executed.

Cara Investments responded to the invitation in late December 1999 by lodging a preliminary expression of interest. The company later obtained an extension to submit a complete proposal by mid-January 2000, but before any updated tender opening date was announced, Cara initiated legal proceedings.

The case sought, among other remedies declarations that Ram had mishandled the RFP process, acted unfairly, and breached legal and contractual obligations owed to the company. Cara Investments also pursued an injunction aimed at preventing the Receiver from finalising any sale until the court examined whether the tender exercise had been properly conducted.

The proceedings expanded in 2001 when Cara Investments succeeded in adding the Bank of Nova Scotia as a defendant. In response to the injunction request, Ram through his attorney gave an undertaking not to advance the tender process until the litigation had concluded.

As a result, no further steps were taken on the sale under his receivership. His role as receiver ended in 2003 after the hotel’s shareholders independently completed the sale of their shares to an external investment group, bringing his involvement with the property to a close.

When the case finally came before then Acting Chief Justice Ian Chang years later, the court took a close look at the legal relationships involved. Justice Chang pointed out that Ram had acted at all times as an agent of the bank during the tender exercise.

Because of this agency relationship, the court found that he could not personally bear contractual liability for decisions made on the bank’s behalf. The judge further concluded that the evidence did not support any claim that Ram had misled bidders or engaged in improper conduct in administering the RFP, especially given the discretionary powers expressly reserved in the tender documents.

With these findings, the court ruled that Cara’s legal challenge lacked foundation, dismissed the action, and ordered the company to pay costs to both Ram and the bank. Cara Investments appealed Justice Chang’s decision to the Court of Appeal, but the court upheld the ruling.

Before the CCJ, attorney-at-law Sanjeev Datadin, appearing for Cara Investments, argued that the injunction did not give the receiver unlimited freedom in administering the RFP and that the duty to act fairly still applied. He maintained that having the power to cancel a tender does not permit arbitrary action, insisting that any such decision must be grounded in proper reasons and communicated to the parties involved—something he said Ram failed to do.

“He [Ram] never exercised his power of cancellation. Up to now, there has been no exercise of that power. He simply stopped, and then proceeded to engage in selling the shares, over which he, as the Receiver/Manager, had no authority. He had authority over the assets of the company; the shares belong to the shareholders,” Datadin told the Bench led by CCJ President Justice Winston Anderson.

Datadin contended that, although Ram admitted he took no further action due to his undertaking to the court, Cara Investments remained entitled to claim damages for his failure to notify the company that its bid had been unsuccessful.

At that point, Justice Peter Jamadar interjected, noting that Datadin had already acknowledged that the Receiver was entitled under clause 2.6 of the RFP to cancel the entire process.

NO BREACH

Meanwhile, Senior Counsel Neil Boston, representing Ram, argued that there was no breach in failing to notify Cara Investments or any of the other bidders about the contract’s cancellation.

He further contended that the RFP constituted an invitation to offer and was not intended to create legally binding contractual obligations.

Boston explained that, according to Chief Justice Chang, the RFP was an ‘invitation to treat.’ He said it was essentially an offer to the invitees that if they submitted a proper offer, Ram could choose to accept it, but any conditional offers could not be accepted.

Senior Counsel Boston said that Cara Investments’ proposal was for US$2 million, whereas the company owed the bank more than US$2.5 million.

Regarding the issue of damages, Boston argued that the claim is misconceived, noting that Cara Investments has not demonstrated a real possibility of securing the contract. He likened the situation to going into a gunfight armed only with a knife: “You’re coming in with US$2 million. The company has debts of US$2.5M-plus.”

Bank of Nova Scotia’s attorney Kamal Ramkarran argued that this is the first time a breach of contract is being claimed on the basis of a failure to communicate.

He insisted that: “There was no contract whatsoever. In this case, there is no process contract or implied contract.”

Ramkarran maintained that the RFP process was never formally concluded, and therefore there could have been no communication indicating that it had ended.

Cara Investments is asking the CCJ, among other things, to overturn the lower courts’ decisions and to award it millions of United States dollars in damages.

The other judges on the panel included Maureen Rajnauth-Lee, Chantal Ononaiwu and Chile Eboe-Osuji.