Library of Congress

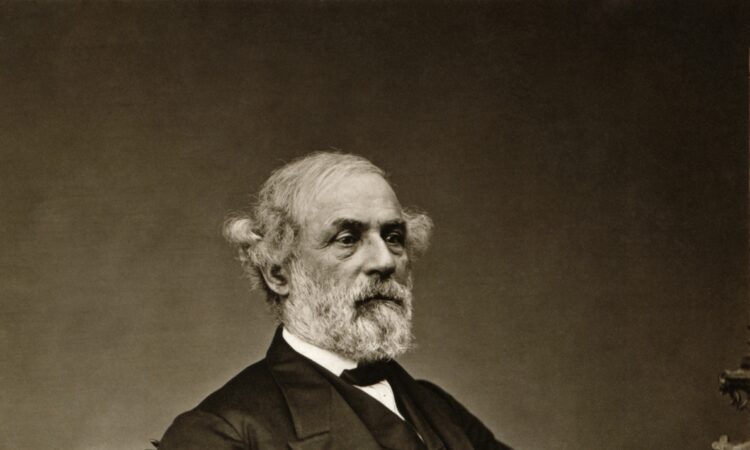

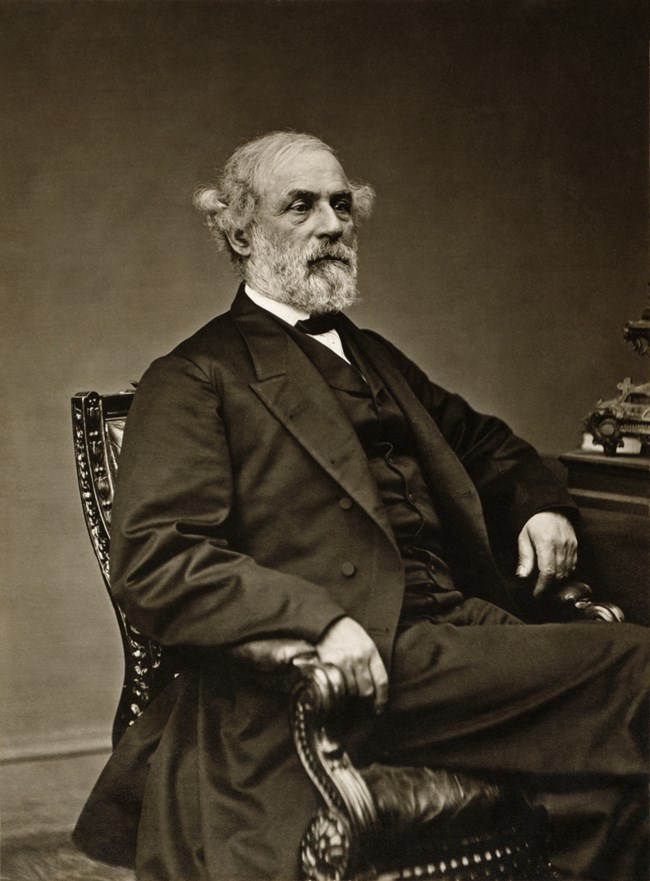

Robert E. Lee is one of the most complex and controversial figures in American history. For generations, Americans have struggled over how to remember this complicated soldier, father, slaveholder, and educator. Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial is the only federally funded national memorial honoring a person who fought against the United States government. However, Arlington House is not a memorial honoring the Confederacy. Instead, the legislation that created the memorial honors Robert E. Lee for very specific reasons, most importantly for his role in promoting peace and reunion following the American Civil War. Historical context is key to understanding the establishment of Arlington House as a national park unit and as a national memorial to Robert E. Lee.

Lee served as a general in the Confederate Army from 1861 to 1865. On April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia was cornered near Appomattox, Virginia by General Ulysses S. Grant’s Union Army of the Potomac. While surrender seemed inevitable, at least one of Lee’s generals suggested he not surrender and instead have the army “take to the woods and bushes” and carry on the fight.[1] Lee declined to take this advice. He decided that this action “would bring on a state of affairs it would take the country years to recover from.”[2] Lee, realizing that further fighting would have no impact on the outcome of the war, made the momentous decision to stop the further bloodshed and surrender his army, even though he “would rather die a thousand deaths.”[3]

Lee left his home, Arlington House, on April 22, 1861 and never returned to the property following the war. He instead settled in Lexington, Virginia and became the president of Washington College (today, Washington & Lee University). Arlington House was seized by federal soldiers during the war, and the United States government officially confiscated the property when his wife, Mary Lee, was unable to pay the taxes on it in 1864. During the war, the U.S. Army transformed the grounds around Arlington House into a military cemetery, today’s Arlington National Cemetery, in an effort to ensure that the Lee family would be unable to return to the house. Additionally, the government established Freedman’s Village, a community of self-emancipated African Americans, on the property in 1863.

While president of Washington College, Lee played a role in efforts to reconcile the North and South. He advocated that the nation not “keep open the sores of war”[4] and encouraged Confederate veterans to move past their shattered fortunes. He urged Southerners to rebuild their country and define themselves again as Americans. He said that he thought “it is the duty of every citizen, in the present condition of the Country, to do all in his power to aid in the restoration of peace and harmony.” In 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant invited Lee to the White House, and Lee accepted. Lee died one year later and was buried in Lexington, Virginia.

After the Civil War, white southerners and northerners took different paths toward rebuilding the nation. Northerners hailed the “Union Triumphant;” the idea that its victory had saved the country. Southerners promoted the “Lost Cause;” the idea that the Confederacy had been righteous in its cause even though it had lost. The two coexisted while the views of African Americans were often suppressed or ignored.

What, though, was to become of Arlington House, now located in the middle of Arlington National Cemetery? In 1874, Lee’s eldest son, George Washington Custis Lee, sued the U.S. government for the return of the Arlington property, claiming that it had been illegally confiscated. In December 1882, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Lee’s favor. A few months later, in March 1883, the federal government purchased the property from Lee for $150,000. The U.S. Army continued to use the Arlington House property as a burial ground.

In the early 20th century, the United Daughters of the Confederacy and former Confederates asked the U.S. Army to turn over Arlington House to them so that they could restore it to honor Lee. The U.S. Army refused, believing that they would use the house to glorify their cause and Lee’s role in the Confederate States.[5]

In 1925, during the Jim Crow era as well as the immediate aftermath of the United States’ successful intervention in World War I, Congress acted to forge a compromise for the future of Arlington House. The U.S. government restored Arlington House to honor Lee, focusing the narrative on Lee’s efforts to promote peace and reunion after the war. The legislation to restore the home reads: “now honor is accorded Robert E. Lee as one of the great military leaders of history, whose exalted character, noble life, and eminent services are recognized and esteemed, and whose manly attributes of precept and example were compelling factors in cementing the American people in bonds of patriotic devotion and action against common external enemies in the war with Spain and in the World War, thus consummating the hope of a reunited country that would again swell the chorus of the Union.” U.S. Representative Louis Cramton of Michigan declared that “it is unprecedented in history for a nation to have gone through as great a struggle as we did in the Civil War”[6] and then to become “so absolutely reunited.” He felt that “there was no man in the South who did more by his precept and example to help bring about that condition than did Robert E. Lee.”[7]