Weekly U.S.-Mexico Border Update: Migration Rises, Darién Gap Data, House Republicans’ Budget

With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

THIS WEEK IN BRIEF:

Arrivals of migrants, mostly asylum seekers, at the U.S.-Mexico border rose to about 8,000 per day this week, a level last seen in April 2023 before the termination of the Title 42 policy. As shelters fill and Border Patrol begins releasing processed migrants on border cities’ streets, it is apparent that migrants’ post-Title 42 “wait and see” period is over. Asylum seekers are again opting to turn themselves in to Border Patrol despite the Biden administration’s “carrot and stick” approach of legal pathways and harsh limits on asylum access. Shelters and migrant routes are similarly full throughout Mexico.

Nearly 82,000 people migrated in August through the treacherous Darién Gap jungle region straddling Colombia and Panama. During the first eight months of 2023, over 330,000 people have taken this once-impenetrable route. So far this year, 60 percent have been citizens of Venezuela and 21 percent have been children, despite the dangers of the journey. In this region of dense forest and difficult terrain, governments have limited short-term options to control territory or channel the flow of people.

As the U.S. government heads for a September 30 budget deadline and an increasingly likely shutdown, the U.S. House of Representatives’ narrow, fractious Republican majority may be proposing a bill that would keep the government open through October 31 in exchange for some radical changes to border and migration policy that the Democratic-majority Senate and the Biden White House would be certain to oppose.

THE FULL UPDATE:

Migrant Apprehensions Rise, Shelters Fill

A March 2022 Department of Homeland Security (DHS) document had explained that, as the Department prepared for an end to the Title 42 pandemic policy, it was preparing for scenarios of “6,000, 12,000 (high) and 18,000 (very high)” encounters with migrants per day arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border. In early May 2023, in the days before Title 42’s May 11 termination, migration reached 11,000 people per day (see WOLA’s May 12 Border Update).

After May 11, though, numbers fell to less than 4,000 people per day border-wide as migrants went into a sort of “wait and see mode.” Many opted to seek legal entries like expanded appointments to seek asylum via the “CBP One” smartphone app. Others waited to see how the Biden administration would apply a new rule limiting access to asylum for people who crossed the border between the official ports of entry.

The post-Title 42 reduction bottomed out in June 2023, when migration fell to its lowest level since February 2021 (3,318 people per day entering Border Patrol custody). Then, arrivals started increasing again. By July, Border Patrol reported 4,279 per day, and 5,871 per day in August, according to data shared with the Wall Street Journal.

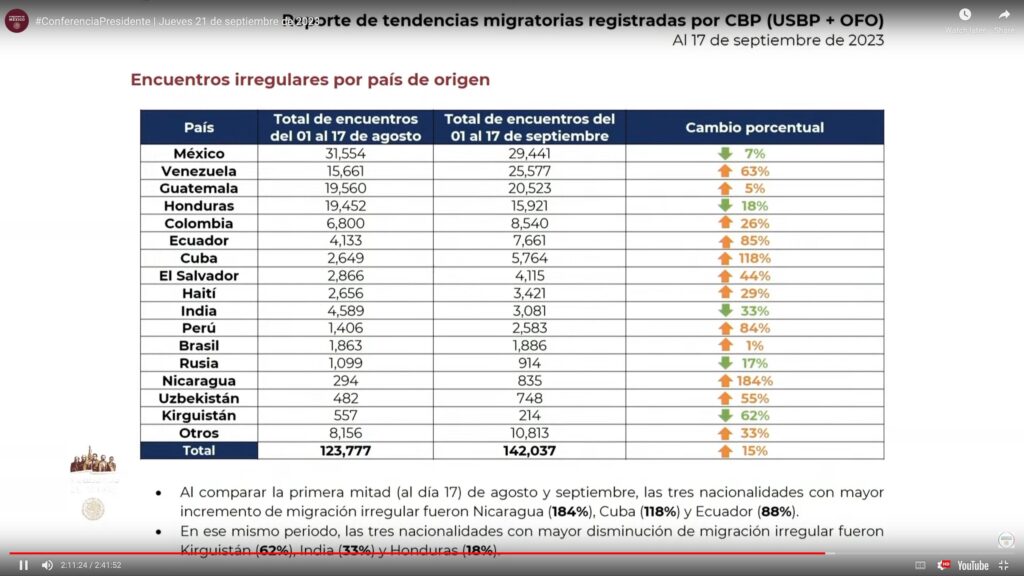

On September 21 the president of Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, displayed a table of preliminary CBP data at his morning news conference, comparing U.S. counts of migration at the border during August 1-17 and September 1-17. The table, combining Border Patrol apprehensions and arrivals at land-border ports of entry, counted 142,000 migrant encounters during the first 17 days of September, or 8,350 people per day. About 1,700 per day are probably port-of-entry arrivals, so Border Patrol’s daily September average has probably been about 6,650 apprehensions per day.

These numbers represent a 15 percent increase in migration from August to September, with notable increases from Cuba, Venezuela and elsewhere in South America.

By the second and third weeks of September, numbers of arriving migrants rose to levels resembling April 2023, the last full month before Title 42 ended. NBC News reported that Border Patrol apprehended more than 7,500 migrants on September 17. The New York Times reported more than 8,000 migrants on September 18, citing the head of Border Patrol’s union, a critic of the Biden administration.

Data shared with NBC indicated that, of the nine sectors into which Border Patrol divides the U.S.-Mexico border, the busiest sectors on September 17 were

- Rio Grande Valley, in south Texas (more than 1,800 migrant apprehensions);

- Del Rio, in mid-Texas (more than 1,600; Del Rio’s chief reported 1,036 per day on social media on September 3-9);

- Tucson, which makes up most of Arizona (more than 1,500; Tucson’s chief reported nearly 1,900 per day on social media on September 8-14);

- El Paso, in west Texas and New Mexico (more than 1,000; El Paso’s municipal migration dashboard reported an average of 1,432 per day for September 17-19, and the New York Times reported 1,609 on September 18);

In addition:

- The chief of Border Patrol’s San Diego sector, which makes up most of California, reported 920 per day between September 13-19 on social media.

- The chief of Border Patrol’s Yuma sector, which includes western Arizona and part of eastern California, reported 200 per day between September 10-16 on social media.

We have seen no September data from Border Patrol’s Big Bend, El Centro, and Laredo sectors, which usually rank seventh through ninth in migration levels.

The numbers indicate that the post-Title 42 “wait and see” period is over, and asylum seekers are again opting to turn themselves in to Border Patrol in areas between the official ports of entry.

“Starting in July,” as the New York Times’ Eileen Sullivan and Miriam Jordan put it, “many people, including families, waiting for an appointment at a port of entry or through a humanitarian parole program, have decided to take their chances and cross the border illegally.” An increasing number of migrants aren’t even aware that legal pathways, like humanitarian parole or appointments via the CBP One smartphone app, even exist. “They don’t know about it,” Pedro Ríos of the American Friends Service Committee’s (AFSC) San Diego office told Sandra Dibble at Voice of San Diego. “The people who are here just recently arrived.”

CBP’s holding capacity is now 23,000, according to a September 20 document, and Border Patrol (a component of CBP) is releasing processed migrants quickly to reduce pressure on its facilities. The same document notes that a deployment of active-duty military personnel supporting CBP—originally slated to end in August, then extended through September—will now be increased again to 800 troops. (This is in addition to 2,500 National Guard personnel deployed under federal authority to support CBP, which in turn is unrelated to a Texas National Guard deployment that is ongoing at the Texas state government’s expense.)

As CBP releases asylum seekers and other migrants, usually with notices to appear in the immigration system to begin asylum claims in their U.S. interior destination cities, border cities are contending with the increased population of released migrants.

El Paso, Texas

El Paso’s municipal government told local media that, with shelters full, the city temporarily housed more than 4,200 migrants in hotels during the week of September 10-16. Migrants “with no place to go,” including families, gather daily in central El Paso’s landmark San Jacinto Plaza, Border Report reported.

John Martin, deputy director of the Opportunity Center for the Homeless, whose welcome center is at capacity, told Border Report that, “unlike the influx of migrants in May of this year and December of last year, this third wave of migrants has been slowly building up over the past three to four weeks, and they expect it to continue to build,” and that “roughly 86% of migrants are Venezuelan.”

In order to allocate more staff to help with processing the large number of arrivals, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) stopped cargo processing at the Bridge of the Americas between Ciudad Juárez and downtown El Paso. While this is not a major cargo route, normally operating between 6:00AM and 2:00PM on weekdays, this plus aggressive “safety inspections” by Texas state police caused long lines of trucks to form. On September 20, CBP announced a temporary closure of vehicle processing and railway processing on two bridges between Eagle Pass, Texas and Piedras Negras, Coahuila.

CBP officials are blaming El Paso’s increase in part on “rumors circulating on social media claiming areas of the Southwest border—specifically in the El Paso Sector—are open to illegal migration,” according to Border Report. “These rumors are absolutely false and yet another dangerous example of bad actors sharing bad information,” read a statement from the agency.

On September 19, Texas state National Guard soldiers—working under the command of Gov. Greg Abbott (R), a critic of the Biden administration— pushed into Mexico hundreds of asylum seekers who had been waiting to turn themselves in to U.S. federal authorities on the El Paso side of the border.

The group had managed to breach coils of razor-sharp concertina wire put down by the state forces along the Rio Grande, and was waiting for as many as two days near the border wall for Border Patrol to appear. Migrants said the National Guardsmen screamed and swore at them, and pointed their rifles at them, until they went back to the Mexico side of the border. (Few, if any, were citizens of Mexico.)

This operation appeared to violate U.S. law. Since the years after World War II, the United States has been among the many nations that, under the Refugee Convention of 1951 and the Refugee Act of 1980, have pledged to provide due process to people on their soil who fear for their lives if returned “on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion,” regardless of how they entered the country. The group of migrants pushed back on September 19 was dozens of yards into U.S. soil and had a legal right to petition for protection in the United States.

This is not the only recent case of Texas forces, working under Gov. Abbott’s so-called “Operation Lone Star,” forcing asylum seekers off of U.S. soil, a human rights violation called refoulement.

- Guardsmen pushed a group of up to 200 Venezuelan migrants back into Ciudad Juárez shortly after the group arrived on the El Paso side on September 12.

- “On a blisteringly hot Wednesday morning,” in Eagle Pass, Human Rights Watch consultant Bob Libal wrote at The Hill, “I saw asylum-seeking families—including at least four babies—stuck on the Texas side of the river under rows of concertina razor wire. One woman was vomiting due to dehydration, while a male companion offered her water from the muddy Rio Grande. Heavily armed Texas and Nebraska National Guard members looked on, but refused repeated requests to give them water for more than an hour. Instead, these families were told to walk three miles downriver. But the place they were directed to is private property, where migrants are often arrested for criminal trespassing, which can result in up to a year in prison.”

- Jessie Fuentes, a kayak tour operator who is suing the Texas state government because its security buildup has damaged his business in Eagle Pass, told the Los Angeles Times that what he has seen from his boat is “one of the most traumatic things a person can witness. You see people being marched up and down the river until they fall or they get tired. My original concern was what they were doing to the river, but then I saw what they were doing to the people.”

Tucson, Arizona

Border Patrol’s Tucson sector was relatively quiet during the Title 42 period, but by July became the number-one sector for migrant encounters (see WOLA’s July 11 Border Update). Shelters are full in Tucson and other southern Arizona cities, amid a sharp increase in Border Patrol releases of processed migrants. Now, the agency has begun “street releases,” dropping migrants off at designated public spaces instead of at shelters.

Tucson’s Casa Alitas shelter network “has been accommodating 1,500 people each night, up from 800 two weeks ago,” the New York Times reported. Street releases are now occurring in Tucson and in smaller cities like Douglas and Bisbee.

Border Patrol may be carrying out some of these releases without notifying local authorities and charities. “Border Patrol is so full, they have not felt it safe to wait because they got to clear out their facilities because there’s just too many people. So they’ve just been releasing people without telling us and that has created some communications and logistical problems that we’ve mostly worked through over the past week,” Mark Evans, a spokesperson for Pima County, Arizona, which includes Tucson, told ABC News.

Border Report spoke to some of a large number of West African migrants, speaking little English or Spanish, who have congregated in Sonoyta, Sonora, Mexico, across the border from Lukeville, Arizona.

San Diego, California

Street releases are also occurring in San Diego, where a robust shelter network is also beyond capacity. The San Diego Rapid Response Network, which has been receiving released migrants for several years, “is full and only able to accept the most vulnerable,” the Los Angeles Times reported. California has offered some support to short-term shelters in the past, but funds are lower now, and bed spaces fewer, due to a state budget deficit.

A county official stated that “3,335 migrants had been dropped off in San Diego” during the five days ending September 18. Hundreds per day are being dropped at sites like the Iris Avenue trolley stop southeast of San Diego. Many migrants there, from Vietnam, Senegal, Guatemala, Eritrea, and elsewhere, “didn’t have money or working cell phones – just U.S. immigration court documents and pieces of paper with hand-written addresses and phone numbers,” Sandra Dibble reported at Voice of San Diego. “Some tried to find Wi-Fi to contact loved ones about flights or hotels. Two men from Senegal briefly borrowed a hot spot from a bus driver,” reported Kate Morrissey at the Los Angeles Times.

Migrants continue to await processing out in the open along the California-Baja California border. An encampment between layers of the double border wall between San Diego and Tijuana may be smaller than it was a week ago (see WOLA’s September 15 Border Update), but persists. Or it could be increasing: “an official familiar with the situation” told the Los Angeles Times, in a story published on September 16, “that the number of people between the walls is growing faster than agents can move them out.”

Hundreds of migrants are also awaiting processing on the U.S. side of the borderline in Jacumba Hot Springs, California, more than 60 miles east of San Diego, where the border wall has gaps due to difficult terrain. At least some of them told the San Diego Union-Tribune they walked there from San Diego. “Two Border Patrol agents managing the encampment sent migrants for processing according to when they arrived, prioritizing families with children,” iNewsource reported. “Many seemed to be staying in the camp between 24 hours to several days.”

In order to provide staff to help with processing migrants, CBP closed the PedWest pedestrian border crossing at the San Ysidro port of entry south of San Diego. San Ysidro has two pedestrian crossings, and PedWest, which was under renovation when the pandemic began, was closed for a few years and in recent months has been open only to northbound border-crossers between 6:00AM and 2:00PM.

The situation in San Diego recalls the increase in migration in the weeks before Title 42’s end, the last time that Border Patrol kept asylum seekers waiting in the space between the border walls (see WOLA’s May 19, 2023 Border Update). However, AFSC’s Pedro Ríos told the Union-Tribune, “What feels different is that Homeland Security is saying this is the new normal.” Rios lamented “a lack of coordination between local, state and federal government on how to address an appropriate humanitarian response.”

Northern Mexico

Mexico, too, is facing challenges from increased northbound migration. The railroad company Ferromex announced a suspension of freight operations on several cargo train lines serving cities along Mexico’s northern border. The move temporarily halts 60 trains and may affect some U.S. trade. The company told NBC News that the reason is an “unprecedented” number of migrants riding atop the cargo trains, which poses a safety hazard.

“Ferromex said there were 1,500 migrants on trains and in the train yards in Torreón, in northern Coahuila state, 800 in Querétaro in central Mexico, 1,000 in Aguascalientes and more than 1,000 on the line running from Chihuahua to Ciudad Juárez, which neighbors El Paso, Texas,” the Wall Street Journal reported. Migrants, the company said, have been injured or killed in about a half-dozen incidents in recent days. The suspension may cost Ferromex 30-40 million pesos (US$1.75 million to US$2.33 million) per day.

Migrant shelters are filling up in Mexican border cities. In Tijuana, the shelter network “is on the verge of collapse amid the arrival of thousands of foreigners who seek to cross to the United States,” the daily Milenio reported. Municipal migration official Enrique Lucero told Milenio that, unlike past migration that was mainly Mexican, Haitian, or from northern Central America, “they are now foreigners from countries like Venezuela, Russia, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, or the Republic of Guinea, most of them displaced by violence.”

Central Mexico

Milenio’s survey of shelters throughout Mexico found them at capacity, too, well south of the U.S. border. In Mexico City, about 200 people are sleeping outside the Cafemin shelter; if migrants travel as families, the shelter takes mothers and children but lacks space for the fathers. In Veracruz, state and municipal authorities’ small shelters are full, and six new facilities are being put together in Poza Rica, Xalapa, Zongolica, Hidalgotitlán, Acayucan, and Uxpanapa. In Oaxaca, “the six municipalities of the Isthmus of Tehuántepec… declared themselves “unable to receive people on the move.” 3,500 migrants are currently stranded at the bus station in the small city of Juchitán, Oaxaca, near the Pacific at Mexico’s narrowest point.

Southern Mexico

In Chiapas, Mexico’s southernmost state bordering Guatemala, local media report of “a new wave of migrants that, according to activists, could exceed 100,000.” “Every morning,” according to Milenio, “between 2,000 and 3,000 migrants seek to complete a procedure at the offices of the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR) or at the National Migration Institute (INM).” Large numbers of migrants are congregating in bus stops at every town along Chiapas’s Pacific coastal highway up to the state capital of Tuxtla Gutiérrez.

On September 18 in Mexico’s southern border-zone city of Tapachula, a large group of mostly Haitian migrants, tired of waiting to begin an asylum process outside the COMAR offices, “knocked over metal barricades and pushed past National Guard officers and police,” the Associated Press reported. “Authorities later convinced many to leave, and no injuries were reported,” AP added, though other reports mentioned minor injuries. The wait for an asylum appointment at Tapachula’s COMAR facility takes “weeks in some cases,” according to AP.

Panama Shares Darién Gap Migration Data After a Record Month

On September 20 Panama shared data, which the New York Times and other outlets had been generally reporting, about August migration through the Darién Gap. A record 81,946 people passed through the Darién region in August 2023. The previous monthly record, set in October 2022, was 59,773.

Until about 2021, this region had been regarded as impenetrable to all but perhaps a few thousand intrepid migrants per year. In the first eight months of this year, 333,704 people have migrated through the Darién. By September 10, Panamanian authorities told the New York Times and repeated in a local news interview, that number had risen to 360,000. Ten years ago, in 2013, the full-year total was 3,051 migrants. In 2011, it was just 281.

So far this year, 60 percent of migrants in this region have been citizens of Venezuela: 201,288 people. In August, the migrant population was 77 percent Venezuelan: 62,700 people. Other countries of significant migration during the first eight months of 2023 include Ecuador (13 percent, 43,536 people), Haiti (12.9 percent, or 42,959 people when including children born in Brazil and Chile), China (4 percent, 12,979 people), and Colombia (3 percent, 11,276 people).

Of migrants taking the 60-mile-plus, smuggler-dominated route through the Darién Gap so far this year, 53 percent have been adult men, 25 percent adult women, 12 percent male children, and 10 percent female children. (The child total, combining genders, rounds to 21 percent.)

“Last Wednesday alone [September 13], 3,200 people entered Bajo Chiquito,” a small town that is one of two main reception sites at the end of the Darién route, the director of Panama’s migration service, Samira Gozaine, told La Estrella de Panamá. Gozaine also estimated that 70 percent of Venezuelan migrants in the Darién had been granted a temporary protected status in Colombia, but then left the country—a statistic that WOLA has not seen cited or confirmed elsewhere.

A September 14 New York Times report attested to the power of organized crime and other dangers to migrants passing through the region’s jungles. So did a September 20 article from the Migration Policy Institute, co-authored by MPI’s Caitlyn Yates and Juan Pappier of Human Rights Watch:

Panamanian authorities have reported finding 124 bodies in the gap between January 2021 and April 2023. These figures most likely represent only a fraction of the number of deaths, based on the authors’ interviews with migrants and humanitarian workers. Drowning seems to be the primary cause of death, though exposure and illnesses were also common.

There are also dangers from other humans. Criminals who operate in the jungle and one-off bandits threaten and rob migrants. Doctors Without Borders has treated more than 200 victims of sexual violence so far this year, most of them women and girls, including cases of rape and sexual abuse committed during robberies.

The territory is very hard for governments or security forces to control. “There are 266 kilometers of jungle with several chasms, numerous trails, many paths that can be taken, and then join together in special areas,” said Gozaine, the Panamanian immigration official.

“The odds seem stacked against efforts to entirely halt trans-Darien movement,” Yates and Pappier point out. “Even if they were not, research shows that blocking established pathways does not end migration, but rather pushes people towards new, more dangerous routes. Migration in and through the Darien Gap is unlikely to end, at least in the near future.”

House Republicans Demand Border Crackdown to Keep Government Open

September 30, the final day of the U.S. government’s 2023 fiscal year, is approaching. If that day passes without a budget for 2024, or without a stopgap “continuing resolution” to keep the government funded temporarily, much of the federal government will shut down for days or weeks, as has happened often in recent years.

As this update is being written, the House of Representatives’ 221 Republican members are searching for a measure that they can support without relying on votes from the chamber’s 212 Democrats. The party’s leadership has submitted, and moved through the Rules Committee, a continuing resolution bill that would keep the government open until October 31—but only in exchange for drastic changes to border security, asylum, and other migration policies.

Following an agreement between hardliners and moderates, House Republican leadership rolled out H.R. 5525, the “Continuing Appropriations and Border Security Enhancement Act,” on September 17. In addition to mandating an 8 percent cut in all non-defense spending, it would incorporate much of H.R. 2, the “Secure the Border Act of 2023,” which passed the House on a 219-213 party-line vote on May 11.

Among many other provisions, the bill would require:

- Increasing the amount of border that is fully walled off to at least 900 miles (currently, about 741 miles of the border have some sort of barrier, 636 of it the kind of “pedestrian” wall that the GOP legislators would prefer).

- Increasing Border Patrol’s staffing to 22,000 agents. (It was at 19,316 as of the 3rd quarter of 2022.)

- Waiving some anti-corruption screening protections in order to ease hiring of new CBP officers and Border Patrol agents.

- Requiring the Biden administration to negotiate a new “Remain in Mexico” program and “safe third country” agreements with El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

- Codifying the Trump-era “transit ban” which prohibits asylum to migrants who did not seek asylum in other countries en route to the United States, with fewer exceptions than the ban that the Biden administration put in place in May 2023 and which is making its way through the U.S. courts.

- Vastly expanding detention of migrant families.

- Easing the repatriation of unaccompanied child migrants.

- Tightly limiting the presidential humanitarian parole authority, which dates back to the 1950s.

- Dramatically narrowing the scope of who would qualify for asylum.

- Charging fees to apply for asylum.

The continuing resolution might not even get introduced, as some of the hardest-line House Republicans oppose any temporary measures. Even if it passed, a bill with these provisions would fail in the Democratic-majority Senate, and be merely the opening bid in a negotiation.

One outcome may involve House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-California), after the government shuts down, agreeing to a more moderate bill and passing it with Democratic support. If McCarthy chooses the route of keeping the government open without hardline border measures, his caucus’s far-right members might attempt to depose him and push to select a different speaker.

Other News

- On September 20 the Biden administration announced that it would re-designate Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for Venezuelan citizens for 18 months, making it available to those in the United States before July 31, 2023. TPS is a migratory status for people whose home countries face calamity, and it allows employment authorization (asylum applicants must wait six months to apply for work permits). “There are currently approximately 242,700 TPS beneficiaries under Venezuela’s existing TPS designation. There are an additional approximately 472,000 nationals of Venezuela who may be eligible under the redesignation of Venezuela,” the DHS announcement reads. The combined total is equal to more than 2 percent of Venezuela’s population before the country’s economic collapse and slide into authoritarianism led a quarter of the population to flee. Read WOLA’s statement on the TPS decision.

- At times of high volume in its processing facilities, CBP separates children as young as eight years old from their parents for as many as four days. That is a finding of the most recent report, filed on September 15, from Dr. Paul Wise, a court-appointed monitor overseeing compliance with the Flores settlement agreement, which stipulates conditions for families and children in detention. “Interviews with parents and children found that there were minimal or no opportunities for phone contact or direct interaction between parent and child. The separation of families and the lack of interaction while in custody do significant, and potentially lasting, harm to children, particularly younger children,” Wise’s report reads. Unlike Trump-era family separations, these are temporary, and families are reunited after processing.

- 199 Mexican migrants died while trying to cross the U.S.-Mexico border between January and June 2023, according to the Mexican government’s Foreign Relations Department. Since 2001, the Department counts 7,927 Mexican citizens who perished trying to cross.

- The DHS Inspector-General issued a report from unannounced inspection visits to CBP holding facilities in the El Paso area in November 2022, a time when Border Patrol’s El Paso stations and processing centers were experiencing a peak of migration. The report found “compliance with standards such as segregating males, females, and juveniles; managing property; providing regularly scheduled meals and showers; and maintaining cleanliness of holding rooms” to be “inconsistent.”

- At USA Today, Will Carless noted that DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas has yet to respond to a letter from 65 Democratic members of Congress asking him about efforts to stamp out political extremism within the ranks of the Department, especially CBP. The letter had given Mayorkas a July 31 deadline to address 20 questions.